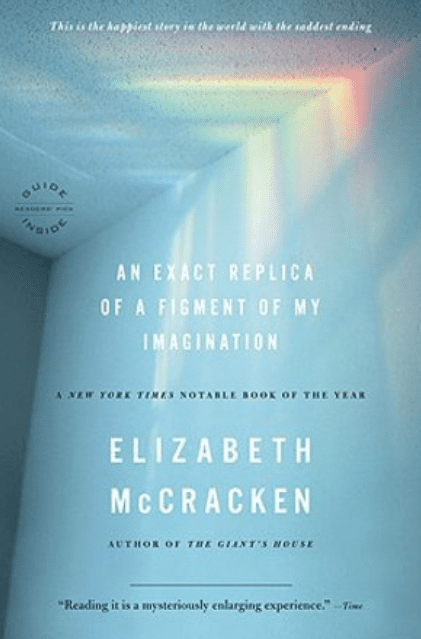

There is no single English word for a stillborn baby. The title of Elizabeth McCracken’s memoir, “An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination” becomes this writer’s sensitive description of that which no common noun can name: a baby that is born dead. It is a phrase derived from both deep love and despair — a phrase that only a mother who has carried a dead baby could create.

There is no single English word for a stillborn baby. The title of Elizabeth McCracken’s memoir, “An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination” becomes this writer’s sensitive description of that which no common noun can name: a baby that is born dead. It is a phrase derived from both deep love and despair — a phrase that only a mother who has carried a dead baby could create.

Elizabeth McCracken and her husband Edward Carey, also a writer, were living in France during her pregnancy in 2006. They had settled in an old farmhouse — once a residence for single mothers — near Bordeaux, anticipating their child’s arrival. McCracken followed the healthful protocol of a mother-to-be, including no wine, no cigarettes. Upon learning the baby’s gender, they affectionately nicknamed the fetus Pudding. Elizabeth McCracken also decided to deliver the baby with the help of a midwife instead of an obstetrician, a common practice in France.

Still, one wonders, after reading McCracken’s memoir of loss, if Pudding might have lived if he was birthed in the United States or England, the homelands of his parents. A New York Times review of “An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination,” suggests McCracken “bends over backward” trying not to accuse her midwife and assistant of negligence, saying “the reader can’t help feeling that McCracken is being too polite. Or is it self-protective?”

Yet, by virtue of her previously acknowledged direct and unsentimental writing style, Elizabeth McCracken is not one to skirt an issue. What she does revisit a number of times in her memoir of loss is the difference in the obstetrics’ medical culture of France, a difference no review of the memoir that I’ve come across brings out.

The French calculate pregnancy due dates differently than in the United States and the United Kingdom. The French count 40 weeks and 6 days from the date of the mother’s last period, whereas, in the U.K. and U.S., it’s one week less. Granted, only 5 percent of babies worldwide are born on their due dates. However, in Elizabeth McCracken’s case, had she been living in her hometown of Newton, Massachusetts, the day during her late pregnancy when she was unable to feel Pudding moving inside her womb, the baby’s fate may have turned out differently.

As it was, “An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination” explains that Elizabeth did book an emergency appointment with the midwife who, much to the parents’ relief, was able to detect a heartbeat. Since Elizabeth had not yet reached her French due date, the midwife sent her home. Had she been past her due date (as she would have been in the United States) Elizabeth would more likely have been sent to a hospital, at least for a sonogram and possibly an induced birth or C-section.

By late that afternoon, it was too late to attempt to save Pudding. Only after that did a hospital sonogram confirm that their son was dead. And adding to the interminable anguish of losing a child, McCracken would still have to deliver her dead child — though the delivery was delayed 36 hours so that doctors could do tests to find out what had caused his death.

Elizabeth McCracken

Credit: PBS Newshour Facebook account

There’s no way of knowing whether a trip to a hospital would have made a difference. Unlike many people looking at Elizabeth McCracken’s experience from the outside, she does not seek answers. Instead, she creates, as a novelist would, the landscape of loss and longing one traverses when they become part of what she calls “the happiest story in the world with the saddest ending.”

Yet, in two significant ways, the story does not end there. In terms of a memoir of loss, McCracken says she sought to write “a book that acknowledges that life goes on but that death goes on, too, that a person who is dead is a long, long story.” And for those who cannot wrap their heads around that both immutable and beautiful thought, she puts it more bluntly by simply stating, “Closure is bullshit.”

Life went on too, in a way that readers like to hear. Three months after the stillbirth, Elizabeth McCracken was pregnant again. The timing haunted her as her second pregnancy began the month Pudding was conceived the year before (which must have made her final month unbearably fearful). By this time she and Edward had fled to England and then to America, swearing they’d never return to France again. Their son Gus was born one year and five days after they lost their first child, a lost child who will always be present in the figment of Elizabeth’s imagined family portraiture.

“An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination” by Elizabeth McCracken

“An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination” by Elizabeth McCracken

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”