Helen MacDonald’s memoir “H is for Hawk” is a beautiful story of grief and healing interwoven with a gripping account of a MacDonald’s relationship with the goshawk she decides to train after her father’s death. Awarded the prestigious Samuel Johnson Prize and the Costa Book of the Year award in 2014, the book was a popular hit as well, rising to Britain’s bestseller list shortly after its release.

Helen MacDonald’s memoir “H is for Hawk” is a beautiful story of grief and healing interwoven with a gripping account of a MacDonald’s relationship with the goshawk she decides to train after her father’s death. Awarded the prestigious Samuel Johnson Prize and the Costa Book of the Year award in 2014, the book was a popular hit as well, rising to Britain’s bestseller list shortly after its release.

Single, childless, and in her 40s, MacDonald was teaching at a local preparatory school when her father, photojournalist Alisdair Macdonald, collapsed on the street and died before reaching the hospital. His death devastated MacDonald, who likens herself to him many times throughout the book. Like him, she is a “watcher,” someone who observes and catalogs life from the sidelines rather than fully immersing themselves in it. And, also like him, she has a deep love of nature, especially birds of prey. The two spent many hours together watching and later training raptors when MacDonald was a child.

After her father’s death, the grieving MacDonald decides to purchase and train a Northern goshawk despite its reputation as the brute of the falconry world — a bird by nature and appearance “bulkier, bloodier, deadlier, scarier,” than other hawks. Her reasons for doing so are unclear, even to her. But as she makes the leather tethers (known as “jesses”) that “would hold me to the hawk, just as they would hold the hawk to me” she finds a measure of comfort in knowing that, as long as its jesses are firmly attached, the bird cannot leave.

Stunning Prose

While the story of Helen and her goshawk Mabel is a captivating one, MacDonald’s stunning prose is what makes “H Is for Hawk” an exceptional book. Her story, after all, is not an unfamiliar one — the human-animal bond has helped heal many a broken heart. But her words are mesmerizing, even breathtaking at times. Take the passage that describes her first meeting with the hawk.

“She is a reptile. A fallen angel. A griffon from the pages of an illuminated bestiary. Something bright and distant, like gold falling through water.”

One can quite literally feel MacDonald’s wonder and the small thrill of horror as she takes in the alien beauty of the bird.

MacDonald and her goshawk Lupin, who she trained after Mabel died

Credit: Mike Birkhead Associates

Later, at her newly rented cottage in the countryside, MacDonald’s first encounters with the goshawk are equally as fraught. After removing Mabel’s hood for the first time, she brings the bird, who is tethered to her perch, to her gloved fist for the first time. The bird “baits,” trying to flee, but is caught up short. MacDonald brings her to the fist again, and again she baits. After the third time, the bird stares at her handler, terrified.

“Her eyes are luminous, silver in the gloom.” MacDonald writes. “Her beak is open. She breathes hot hawk breath in my face…Her scaled yellow toes and curved black talons grip the glove tightly. I feel like I’m holding a flaming torch. I can feel the heat of her fear on my face…”

And so the dance begins.

Love and Letting Go

The remainder of “H Is for Hawk” is part love story, part nature tale. Mabel and MacDonald develop an ever-deepening bond as the raptor (technically an accipter) slowly learns to fly free and return. At first terrified when she removes Mabel’s jesses, MacDonald slowly begins to trust that the hawk will come back. And as she does so, she begins to remember what happiness is. “There was nothing that was such a salve to my grieving heart as the hawk returning,” she writes.

Credit: Mike Birkhead Associates

Meanwhile, MacDonald makes uneven progress — at times feeling that she has given up her identity and become as wild, anxious and solitary as the goshawk she trains. She recognizes that she has withdrawn from the world, isolating herself to the degree that nothing exists but her relationship with the hawk. And she knows this is unhealthy. Yet she cannot, at least for a time, bring herself to break free. She hunts with Mabel, breaking the necks of the rabbits and pheasants the bird brings to ground before she can eat them alive. (Goshawks don’t kill their prey before they devour them.) Though it is an act of compassion, it seems to underscore the wildness that has entered MacDonald’s heart. “Hands are for other human hands to hold,” she muses. “They should not be reserved exclusively as perches for hawks.”

Redemption

Towards the end of “H is for Hawk” MacDonald is awakened by an earthquake in the middle of the night. Confused and terrified, she runs to check on Mabel, sure that the bird is as frightened as she. But instead, she finds Mabel sitting on her perch, asleep.

“She felt the tremors,” MacDonald writes. “And then she went back to sleep, entirely unmoved by the moving earth. The quake brought no panic, no fear, no sense of wrongness to her at all. She’s at home in the world. She’s here. She ducks her head upside down, pleased to see me, shakes her feathers into a fluffy mop of contentment, and then, as I sit with her, she slowly closes her eyes, tucks her head back into her feathers, and sleeps.” And at that moment, MacDonald writes, she becomes “more than a hawk. She feels like a protecting spirit. My little household god.”

“I had thought the world was ending, but my hawk saved me again,” she writes, “and all the terror was gone.”

And that’s when the true healing began.

Postscript: Mabel and MacDonald lived together until Mabel’s sudden death in 2013, a year before “H Is for Hawk” was released. In 2017, MacDonald trained another hawk, Lupin (pictured above) for a documentary shown on PBS.

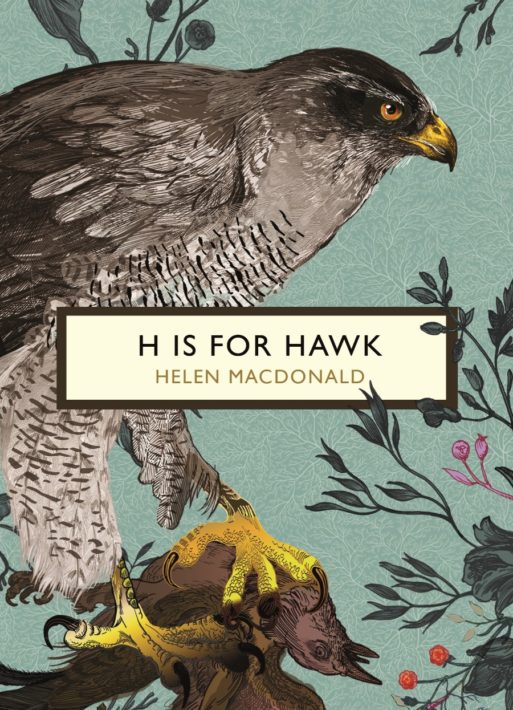

“H is for Hawk” by Helen MacDonald

“H is for Hawk” by Helen MacDonald

Terminal Sedation at the End of Life

Terminal Sedation at the End of Life

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!