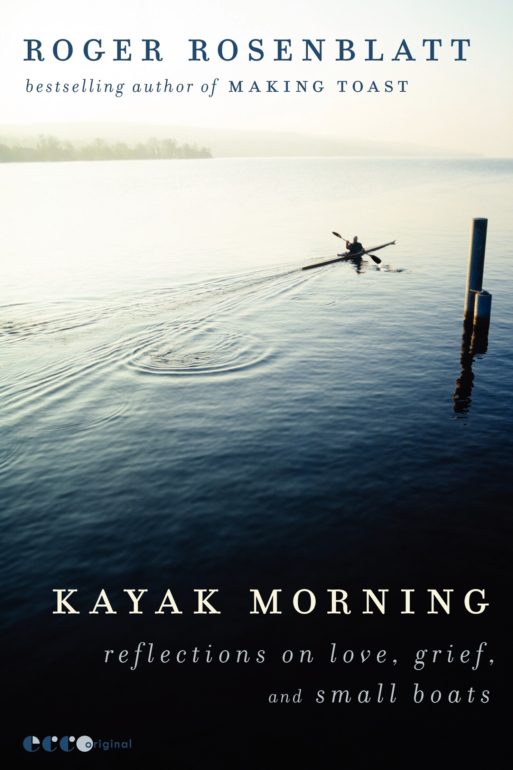

In his 2010 memoir, Making Toast, Roger Rosenblatt tells his story about loss after losing his daughter, Amy, unexpectedly. With a series of snippets similar to diary entries, Rosenblatt detailed his struggle with the aftermath and how he coped by helping take care of his grandchildren. Much like this first attempt to describe his experience, Kayak Morning tackles the grieving process from many different angles. Unlike his previous memoir, though, it goes deeper into the mind of someone dealing with loss.

In his 2010 memoir, Making Toast, Roger Rosenblatt tells his story about loss after losing his daughter, Amy, unexpectedly. With a series of snippets similar to diary entries, Rosenblatt detailed his struggle with the aftermath and how he coped by helping take care of his grandchildren. Much like this first attempt to describe his experience, Kayak Morning tackles the grieving process from many different angles. Unlike his previous memoir, though, it goes deeper into the mind of someone dealing with loss.

The first sentence of this book is particularly striking. “Two and a half years after our thirty-eight-year-old daughter, Amy, died of an undetected anomalous right coronary artery,” he says, “I have taken up kayaking.” Rosenblatt sums up in one sentence the root of his pain and spends the rest of the book exploring it as he explores the local rivers and creeks. The language begins with a straightforward jolt that says nothing about the tone it will soon take and sustain. As it is often the case with Rosenblatt, he has a way of putting simple things beautifully. Here, he adapts the poetic language necessary to reflect on typically impenetrable subjects.

“Unlike his previous memoir, though, it goes deeper into the mind of someone dealing with loss.”

As an English professor, Rosenblatt uses some of his most familiar resources to try to understand the ins and outs of grief. Dictionary entries, poetry, quotes, and anecdotes pepper this memoir that is more a collection of pieces than an organized narrative. And in that way, form could be following function. After losing his daughter, Rosenblatt’s life no longer fits together the same way. One morning on the water, he seems to contemplate the natural order of things, saying, “Here, the ducks whettle out in their crazy syntax. The swans sail by with mud on their keels. The tides rummage with the pebbles. The sunlight hones the edge of the whited houses, etching guillotine blades on the walls. What I liked about Stevens was his rage for order. Things as they should be. Everyone in his place” (16). He indirectly addresses his grief rather than telling us about it.

no longer fits together the same way. One morning on the water, he seems to contemplate the natural order of things, saying, “Here, the ducks whettle out in their crazy syntax. The swans sail by with mud on their keels. The tides rummage with the pebbles. The sunlight hones the edge of the whited houses, etching guillotine blades on the walls. What I liked about Stevens was his rage for order. Things as they should be. Everyone in his place” (16). He indirectly addresses his grief rather than telling us about it.

“Dictionary entries, poetry, quotes, and anecdotes pepper this memoir that is more a collection of pieces than an organized narrative.”

“What is the difference between grief and mourning?” he writes, “Mourning has company” (39). Through his physical isolation on the water, we also pick up on the psychological isolation he has in sorrow. The definition he has for grief, though, is so surprisingly lovely I’d like to think we could find it in every dictionary. “Grief. The state of mind brought about when love, having lost to death, learns to breathe beside it. See also love” (146). And that, more than anything, speaks to the book as a whole. While spending most of our time avoiding heartache, we forget about the love that necessarily precedes it. Without grief, how do we measure love?

To read our review of Making Toast, click here: http://blog.sevenponds.com/lending-insight/book-review-making-toast

Kayak Morning by Roger Rosenblatt

Kayak Morning by Roger Rosenblatt

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull