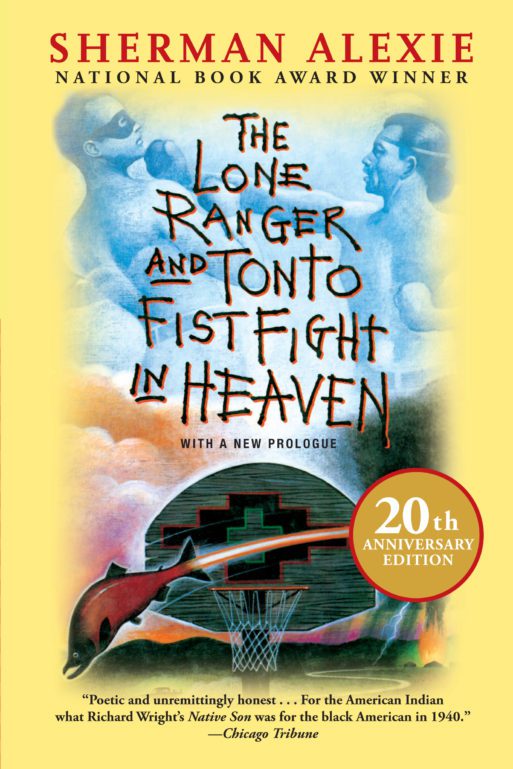

A while back, I reviewed the 1998 film Smoke Signals on the SevenPonds blog. This inspired me to read the collection of short stories on which the film was based. The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven is a magical work of literature that confronts topics of loss and death with dark humor. The collection is by Native American author Sherman Alexie, who also wrote the screenplay for Smoke Signals. Most of the stories in the collection are based on Alexie’s own experiences growing up on a reservation near Spokane, Washington and deal deftly with serious subjects like Native American family dysfunction, broken dreams, alcoholism, loss and death.

A while back, I reviewed the 1998 film Smoke Signals on the SevenPonds blog. This inspired me to read the collection of short stories on which the film was based. The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven is a magical work of literature that confronts topics of loss and death with dark humor. The collection is by Native American author Sherman Alexie, who also wrote the screenplay for Smoke Signals. Most of the stories in the collection are based on Alexie’s own experiences growing up on a reservation near Spokane, Washington and deal deftly with serious subjects like Native American family dysfunction, broken dreams, alcoholism, loss and death.

The story “This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona” is where Smoke Signals was born: in a short, bittersweet tale of the two Native Americans Victor and Thomas, who travel to Arizona to collect the ashes of Victor’s father. Other stories are loosely related, with an ubiquitous “Victor” who often appears as the protagonist. It’s uncertain whether all of the stories completely overlap or exist on the same temporal plane — but many employ a sense of dark humor in the face of loss and death.

In “A Train Is An Order of Occurrence Designed to Lead to Some Result,” the older Native American Samuel Builds-the-Fire (grandfather to Thomas) lives and works in downtown Spokane as the maid at a seedy motel. He goes to work early on his birthday, a day in which he has received worryingly little correspondence from his children, only to discover he has been fired. Unlike most other Alexie characters, Samuel has never consumed a drop of alcohol in his life — but after getting fired, he heads straight for the bar.

At closing time, Samuel was pushed out the door into the street. He staggered from locked door to locked door, believing that any open door meant he was home. He pissed his pants. He couldn’t believe he lost his job. He climbed up an embankment and stood on the Union Pacific Railroad tracks that passed through and over the middle of the city.

Samuel was elevated exactly fourteen feet and seven inches above the rest of the world.

As the whistle grows louder and closer, Samuel sings an old song, then trips and falls face-down on the tracks.

Samuel closed his hands and his eyes.

Sometimes it’s called passing out and sometimes it’s just pretending to be asleep.

It’s in this way that the story ends: a bitter resignation to the end of life, to loss and death. It’s a bit startling, since Samuel is almost optimistic about his birthday in the story’s beginning.

Coursing through every story is a deep and abiding cynicism about the condition of Native American life in modern America. There’s a palpable sense of loss and a righteous antagonism to the oppressive white institutions of the state. There’s even a reliance on clichés (cowboys and Indians, Custer, Wounded Knee, ghost dancing) to tie the tragedies of the individual characters to the wider tragedy of Native American displacement and genocide in the making of the United States.

In “The Approximate Size of My Favorite Tumor,” a narrator discovers he has cancer and then alienates his wife by ceaselessly making jokes about it. The narrator is the type of person who has to constantly make jokes — his only defense against life is to make people laugh. This almost gets him into trouble when he is pulled over by a racist state trooper, who demands a bribe of ninety-nine dollars.

“Hey,” I said. “Take it all. That extra dollar is a tip, you know? Your service has been excellent.”

When the trooper throws the pennies back at them before leaving, they’re happy. It’s just enough gas money to get them home.

But Norma leaves him when he won’t stop joking about his terminal cancer. She travels the Western United States, sending him occasional postcards. He endures hospital treatments until he is eventually released, as his doctors think he’ll be more comfortable at home. He orders stationery that reads “FROM THE DEATH BED OF JAMES MANY HORSES, III,” even though he is the only James Many Horses.

One day, Norma returns. James asks her why:

“Really, why’d you come back?”

“Because someone needs to help you die the right way,” she said. “And we both know that dying ain’t something you ever done before.”

I had to agree with that.

“And maybe,” she said, “because making fry bread and helping people die are the last two things Indians are good at.”

“Well,” I said. “At least you’re good at one of them.”

And we laughed.

So, the two accept the inevitability of his death in the same way they embrace all of the problems throughout their marriage: with humor; it’s a way of not crying or screaming at the tragedy of it all. In this collection, Alexie excels at taking the most hopeless of situations and conveying them with humor and familiarity — and that includes the difficult subject of loss.

Related Articles:

“The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven” by Sherman Alexie

“The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven” by Sherman Alexie

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?