I’d never meditated on “A Moveable Feast“’s relationship with death. Sure, I’d thought of Ernest Hemingway’s classic as a book about the obvious: hunger and gratitude, honesty and unrelenting love. F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald were champions of the latter themes, given their tumultuous relationship in the book. The two were so in love, and like so many characters in “A Moveable Feast”, you wanted both to slap and to congratulate them for their untethered passion. But so was the nature of Hemingway’s Paris in the ‘20s: a la vie en rose and “anything goes” kind of town. At least ostensibly.

I’d never meditated on “A Moveable Feast“’s relationship with death. Sure, I’d thought of Ernest Hemingway’s classic as a book about the obvious: hunger and gratitude, honesty and unrelenting love. F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald were champions of the latter themes, given their tumultuous relationship in the book. The two were so in love, and like so many characters in “A Moveable Feast”, you wanted both to slap and to congratulate them for their untethered passion. But so was the nature of Hemingway’s Paris in the ‘20s: a la vie en rose and “anything goes” kind of town. At least ostensibly.

Hovering over Hemingway’s romantic cafés and ateliers is the fresh memory of WWI. And so many of Hemingway’s character traits are defined by the repercussions of having survived those years of war and constant death – particularly his need for “truthful prose,” and his disdain for anyone who sought otherwise.

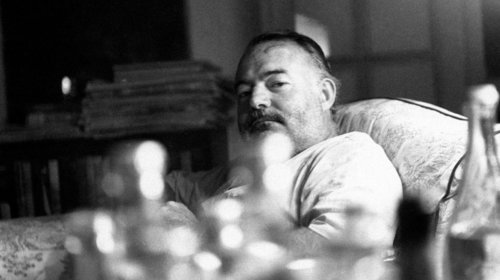

Hemingway was always defined by his impatience. But it took a second reading for me to realize this wasn’t an inherent impatience, but a post-war hunger to live meaningfully; a thirst for life that was born from too much time around death.

“A Moveable Feast” was published posthumously in 1964, so we can only imagine the revisions Hemingway would’ve made before his “personal life” hit the shelves. There’s only a vague sense of direction and plot in the book, which reads like a journal and goes with the flow of the Seine river.

We learn what it means for Hemingway and his (first) wife Hadley to be “poor and happy” with their son Bumby. We drink wine with Ezra Pound and James Joyce while gossiping about T.S. Elliot. And by the book’s end, we realize “A Moveable Feast” is less of a novel than it is a collection of portraits.

“A Moveable Feast” threw a spotlight on post-WWI Paris that, even today, hasn’t budged from its literary pedestal. Hemingway was stingy when it came to dispensing adjectives and similes, opting for an unembellished prose style. The author’s sentences are so unforgivingly present that they convinced readers, as they still do, of holding a kind of lucidity about Paris. And if we listen to those sentences with a glass of eau-de-vie in hand, as was Hemingway’s habit with Gertrude Stein, there’s the hope that we might become privy to a kind of quiet magic about the City of Lights.

I admire the preciousness Hemingway has for life without writing about it “preciously.” And when thinking about the role death plays in this appreciation, the relationship becomes clear: WWI perches itself quietly in many scenes where its very absence makes the taste of bread so much sweeter, or a cramped apartment suddenly charming.

Then there are chapters like “The Man Who Marked for Death.” In this episode, Hemingway goes out for dinner with poet Ernest Walsh. For Hemingway, Walsh is dishonest, “dark, intense, and clearly marked for death as a character is marked for death in a motion picture.” Walsh talks about what it is that makes someone appear “marked for death,” to which Hemingway writes:

“I looked at him and his marked-for-death look and I thought, you con man conning me with your con. I’ve seen a battalion in the dust on the road, a third of them, the dust for all, and your and your marked for death look…Death was not conning with him. It was coming all right.”

Endless scenes are passed at the cafe, “Closerie de Lilas” in the book. Today, the cafe remains a fixture of Paris.

(Credit: Hotel Paris Rive Gauche)

It’s an important moment of anger for the novel. Walsh speaks with authority on death’s timing, to which Hemingway argues that we can’t understand it. If anything, he finds death indifferent. Every person will meet the same “dust for all” fate – and to claim some carry it more than others is “a con” for Ernest Hemingway.

“A Moveable Feast” is one of the strongest relics of The Lost Generation of writers. “That is what you are,” Stein famously said to Hemingway about his creative clique, “That’s what you all are … all of you young people who served in [WWI].” Yet, after re-reading “A Moveable Feast”, I’d have to argue with Ms. Stein. Hemingway lived in close contact with death in a way I never will. But to think I’m ultimately any further from it than him, or anyone else, would be a con. We’re all “Lost” in our attempt to understand death’s logic – but we can choose, like Hemingway, to indulge ourselves in a life richly lived. And that’s worth raising a glass of rosé.

“A Moveable Feast” by Ernest Hemingway

“A Moveable Feast” by Ernest Hemingway

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull