The opening scene of “Good Grief” aptly sets the stage for Daniel Levy’s directorial film debut, in that it features rich visuals and warm vibes. But the film ultimately lacks the depth we’re left desperately craving by the end of the film.

The opening scene of “Good Grief” aptly sets the stage for Daniel Levy’s directorial film debut, in that it features rich visuals and warm vibes. But the film ultimately lacks the depth we’re left desperately craving by the end of the film.

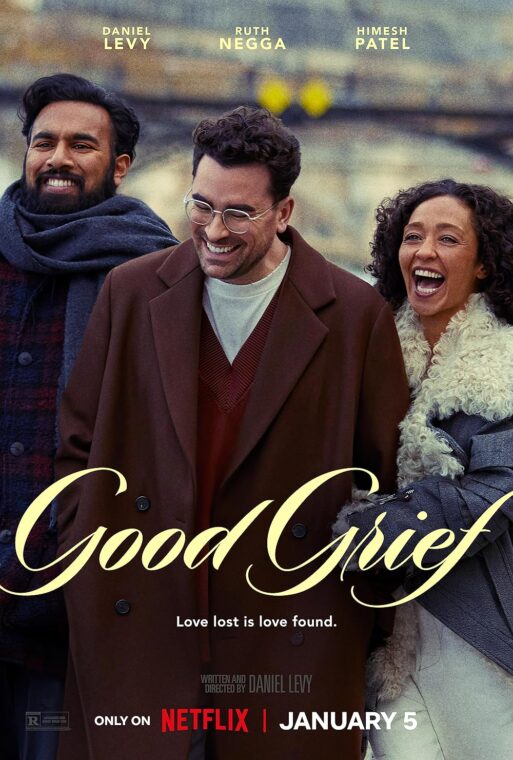

“Good Grief” was written, directed, and produced by Levy, who also stars in the film as Marc – a gay, expat artist in his late 30s. We are introduced during a lush holiday party thrown by Marc and his husband Oliver (Luke Evans) — an A-list Ya-Lit author — and watch as life quickly takes a turn when Oliver dies unexpectedly, sending Marc into a tailspin. As the story progresses, Marc discovers things about his late husband that leads him to invite his two best friends, Sophie (the fantastic Ruth Negga) and Thomas (Himesh Patel) to Paris for a weekend to seek some joy (and secretly, some answers to Marc’s questions).

Dan Levy as Marc

Credit: Tudum by Netflix

To Levy’s credit, “Good Grief” is an extended study of complicated grief, a realistic and intimate portrayal of the messiness involved. (My one complaint is the convenient fact that Marc and Oliver possess the incomprehensible level of wealth that allows Marc to swan through his mourning period with zero concern about his finances.) One particularly poignant scene was during Oliver’s funeral, when his father (the brilliant David Bradley) tearfully expresses his regret over mistakes he made raising his gay son.

Although Marc’s year of intense mourning is condensed into about 15 minutes, the film manages to capture all the different faces grief can wear. We follow Marc alternately wallowing, shuffling around his ornate London flat, but also attempting to seek normalcy by attending gym classes and trying to pursue things he used to enjoy. His friends — Sophie, the life of the party who always ends up heartbroken by her poor choice of lovers, and Thomas, Marc’s ex-lover-turned-incredibly-supportive platonic soulmate — show amazing patience with Marc’s all-consuming grief. (We are treated to several conversations between them where we see his inadvertent self-absorption –“Do I look older? I feel like I’ve aged…” — handled with grace). But after twelve months of unquestioning support, Sophie and Thomas are begging Marc to move on.

[Sophie:] “We have been here for you whenever you’ve needed us for almost a year now. We built you the nest, and we sat on you for a year. It’s time to hatch.”

This turning point in the film grants us an all-too-brief window into an often unacknowledged aspect of loss: the protective narcissism of mourning and the grueling process of getting that shell to crack open. But when Marc, Sophie, and Thomas escape to Paris, the wonderful vulnerability that existed between them seems to vanish. Oliver’s death (and the secrets subsequently revealed) has fundamentally changed Marc, and suddenly he is unable to be completely open with them. This loss complicates their relationship, and Marc feels unable to reach out because his friends are suffering their own “messy secrets and hard truths.”

A behind-the-scenes shot of Dan Levy directing “Good Grief”

Credit: Chris Baker/Netflix

Ultimately, while Levy is successful in creating a beautiful movie that manages to avoid some cringey Hollywood clichés, the story itself never really escapes its two-dimensional nature. Sophie and Thomas’s characters aren’t explored deeply enough for us to truly care about their respective arcs, which is doubly disappointing knowing how skilled Levy has been in the past with this kind of work on Schitt’s Creek. And while we’re rooting for Marc to finally process his loss, it feels cheap for him to do so by finding a new love interest.

In an interview with NPR, Levy said that the movie “came from my own confusion around feelings of grief and what it all meant and whether I was honoring the people that I was mourning appropriately. In my case, it was my grandmother. And then five days before I wrote the screenplay, my dog of 10 years passed away, and so it was a very raw and confusing time. I couldn’t speak the feelings. I could only write them, and the feelings in it were the only way I could kind of make sense of my own.” Maybe what we are sensing, as viewers, is Levy’s unwitting hesitation to truly touch those raw nerves in order to fully process them.

“Good Grief” by Dan Levy

“Good Grief” by Dan Levy

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead