No health crisis in modern times has approached the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s in scope or impact. In the two decades between 1980 and 2000, nearly 780,000 Americans were diagnosed with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, and at least 448,000 of those people died. The virus decimated the gay community, especially in San Francisco, where at least 20,000 people, most of them gay men, have died of AIDS since 1981. Another 6000 are still living with the disease today.

No health crisis in modern times has approached the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s in scope or impact. In the two decades between 1980 and 2000, nearly 780,000 Americans were diagnosed with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, and at least 448,000 of those people died. The virus decimated the gay community, especially in San Francisco, where at least 20,000 people, most of them gay men, have died of AIDS since 1981. Another 6000 are still living with the disease today.

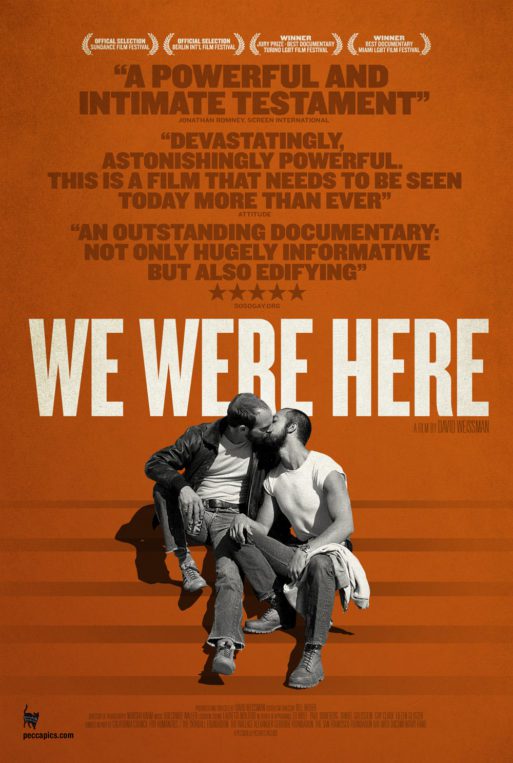

“We Were Here” is a powerful film that documents the San Francisco AIDS epidemic in heartbreaking detail. Told by five survivors — four gay men and a female nurse who worked on the San Francisco General AIDS ward as the epidemic took hold, it is a devastating account of the horrific toll the illness took, not only on its victims but on those who loved and cared for them.

Directors David Weissman and Bill Weber pull no punches in their award-winning film. The documentary revolves around poignant, often tearful interviews with people who lost intimate partners, co-workers and friends, and photo after photo of beautiful young men ravaged by the disease. What makes the film bearable is the juxtaposition of this almost unfathomable suffering with the incredible heroism, selflessness, and courage that the men and women of the city’s gay and lesbian community displayed during what was arguably one of the worst disasters in U.S. history.

Paul Boneberg

Credit: thefilmcollaborative.org

The central characters in the documentary played different roles as the crisis unfolded and tell their stories through a different lens. Paul Boneberg, one of the city’s first gay activists and the former executive director of San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society, speaks eloquently of the way the community came together, opening food banks and bringing meals, medicine and companionship to hundreds and eventually thousands of men who were too ill to leave their homes. “If you’re ever facing a natural disaster,” he says, “you should be so lucky as to be in a community like the queer community in San Francisco.”

Eileen Glutzer, a nurse who worked on SF General’s 5B, (which later became the hospital’s designated AIDS unit) recalls the countless men who died under her care and the desperate struggle to understand the disease and find a cure. In one of the most heart-rending parts of the film, she talks about asking young AIDS victims who had gone blind from CMV retinitis if they would consent to donate their eyes for research after they died. With tears in her eyes, she recounts the terrible ordeal of being with their bodies as their eyes were removed and placed in a plastic jar. “These were men I loved,” she says.

And then there’s Ed Wolf, who moved to San Francisco to be with gay men like himself, but just wasn’t able to “get into the anonymous sex thing.” Even in the incredibly diverse and accepting gay community of San Francisco, he felt like an outsider — until the epidemic struck. Then he finally found a way to connect — becoming one of the first AIDS volunteers with the Shanti Project and caring for sick and dying gay men.

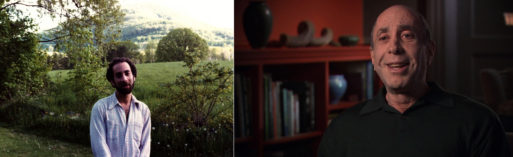

But by far the most touching stories in the film come from Daniel Goldstein, a New York native who moved to San Francisco in the 1970s to study art and “meet a gorgeous blond surfer.” A highly successful and sought after artist by the time he was in his 30s, he had no shortage of friends, lovers, and intimate partners, many of whom simply disappeared as the epidemic began. Then he, too, was diagnosed with AIDS. As he became more and more ill, he watched helplessly as everyone he loved and cared about succumbed to the disease. After his lover died of a cerebral aneurysm as Goldstein drove frantically through the city in a vain attempt to get him to the hospital in time to save his life, he became suicidal, the artist admits. “It just didn’t make sense to stick around anymore,” he says.

Daniel Goldstein then and now

Credit: thefilmcollaborative.org

But stick around he did. Even in the face of so much loss, he persevered and is still alive and living in San Francisco today. But, he admits sadly, he is the only one of his once beloved community who is. “I have so many friends who died so young,” he says in one of the closing scenes in the film. “That to me is the most painful part. What would the world be like now if they were alive?”

“We Were Here” is an important film. At a time when new HIV infections in certain U.S. populations are again on the rise, it is a grim reminder of how catastrophic HIV and AIDS were — and can be again. But even more importantly, it is proof that a community that works together can overcome even the most catastrophic events. Given our nation’s current health care climate, that’s a reassuring thing to know.

“We Were Here” by David Weissman and Bill Weber

“We Were Here” by David Weissman and Bill Weber

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”