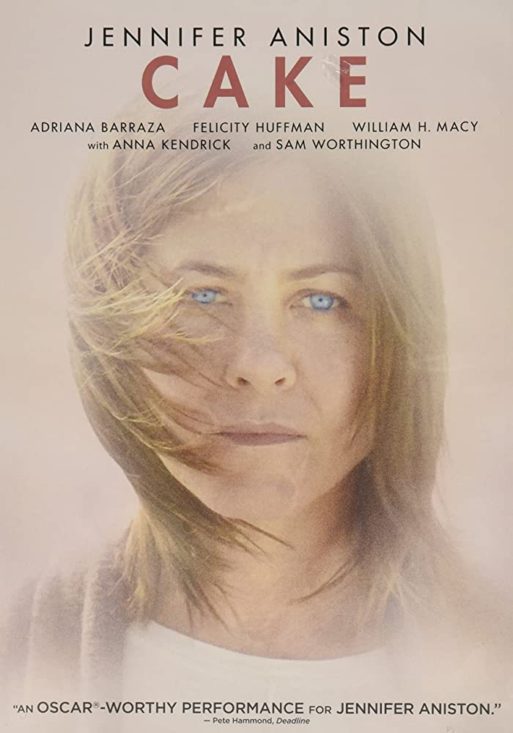

When Cake came out in theaters last year, I remember hearing all the buzz about how “America’s Sweetheart” Jennifer Aniston made herself completely unglamorous in the role of a woman dealing with chronic pain (along and the snub she received when she didn’t get an Academy Award nomination). To be honest, I’m not really a Jennifer Aniston fan, but I was curious about all the buzz, so I caught the film recently on Netflix. I must say, Aniston is far from anyone’s “sweetheart” in this film. Rather, she is highly acerbic — with so much anger bubbling at the surface — to the point that she pushes those close to her away, including her on-screen husband. As her character, Claire Bennett, best puts it, “Tell me a story where everything works out in the end for the evil witch.”

When Cake came out in theaters last year, I remember hearing all the buzz about how “America’s Sweetheart” Jennifer Aniston made herself completely unglamorous in the role of a woman dealing with chronic pain (along and the snub she received when she didn’t get an Academy Award nomination). To be honest, I’m not really a Jennifer Aniston fan, but I was curious about all the buzz, so I caught the film recently on Netflix. I must say, Aniston is far from anyone’s “sweetheart” in this film. Rather, she is highly acerbic — with so much anger bubbling at the surface — to the point that she pushes those close to her away, including her on-screen husband. As her character, Claire Bennett, best puts it, “Tell me a story where everything works out in the end for the evil witch.”

While everyone else shares their tearful words of anger, Claire delivers blunt punches to the gut with her direct questions and commentary about how the woman who committed suicide was lucky to escape the chronic pain of life.

Daniel Barnz’s Cake slowly — albeit a bit too slowly — unravels the mysteries behind the main source for Claire’s chronic physical and emotional pain. Cake starts off promising with a scene of the support group for women dealing with chronic pain to which Claire belongs, where everyone vents their anger at the leader, played by the talented Felicity Huffman, after one of the characters recently committed suicide. While everyone else shares their tearful words of anger, Claire delivers blunt punches to the gut with her direct questions and commentary about how the woman who committed suicide was lucky to escape the chronic pain of life. This ultimately leads to her being banned from the support group.

In a way, these visions act as stepping stones to Claire learning to cope better and grow from the complicated grief she has been struggling with for over a year.

Banishment from the support group leads to Claire’s constant visions of the woman who commited suicide, Nina Collins (played by Anna Kendrick). Oftentimes, these visions flicker between clarifying why Claire is so angry at everything and confusing the film’s viewers about what is actually going on. In a way, these visions act as stepping stones to Claire learning to cope better and grow from the complicated grief she has been struggling with for over a year. During one of these visions, Claire tells the “ghost” of Nina, “I hate to break it you, but I don’t believe in ghosts.” Nina replies, “That doesn’t mean you’re not a coward.” Over time, Claire’s obsession with Nina’s fate leads to her befriending Nina’s widower as well as realizing how much her anger and acerbic words and actions have isolated her from loved ones she has deeply hurt.

So why does Claire possess so much anger and what exactly caused her to be in constant physical and emotional chronic pain? Unfortunately, for viewers, Barnz decides to drag out the process of answering our burning questions. Granted, this prompts decent acting, on Aniston’s part, to display some quite raw emotions for someone dealing with complicated grief. Keeping the questions I had unanswered for so long left a lingering irritation with the film as a whole.

When viewers finally learn that the instigator was a car crash that killed her young son and left her partially disabled, the rest of the movie seems to drag on for longer than necessary. While Claire does seem to finally be making amends with the mistakes she has made in her life in the aftermath of the tragic loss of her son and the complicated grief she’s been enduring, I, as a viewer, was left feeling bored and far from supportive of her gradual transformation. I couldn’t help counting down the minutes until the end and fervently hoping that better and more relatable movies about a complicated grief of such a nature would be out there for me to consume and challenge me, while also ultimately keeping me entertained and wanting to root for, and sympathize with, the protagonist’s journey.

Cake (2014) by Daniel Barnz

Cake (2014) by Daniel Barnz

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?