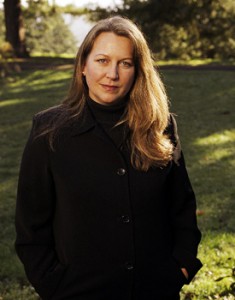

“The first time I cheated on my husband, my mother had been dead for exactly one week.” With this powerful statement, Cheryl Strayed begins her personal story of love, life, and death that could very well alter the way we think about the “traditional” grieving process. On the surface, her story concerns the dissolution of her marriage in the aftermath of her mother’s death. Engaging in several extramarital affairs, she seeks refuge from the emptiness in the arms of complete strangers. On a deeper level, Strayed tackles issues such as denying one’s grief, society imposing boundaries on the process, and rediscovering oneself in the midst of tremendous upheaval.

“The first time I cheated on my husband, my mother had been dead for exactly one week.” With this powerful statement, Cheryl Strayed begins her personal story of love, life, and death that could very well alter the way we think about the “traditional” grieving process. On the surface, her story concerns the dissolution of her marriage in the aftermath of her mother’s death. Engaging in several extramarital affairs, she seeks refuge from the emptiness in the arms of complete strangers. On a deeper level, Strayed tackles issues such as denying one’s grief, society imposing boundaries on the process, and rediscovering oneself in the midst of tremendous upheaval.

After losing her mother to cancer at the young age of twenty-two, Strayed struggles to grasp her new reality. Constant reminders of her mother’s absence cause her to feel great pain, and yet, she puts significant effort into feeling hardly anything at all. “We are not allowed this,” she says, “We are allowed to be deeply into basketball, or Buddhism, or Star Trek, or jazz, but we are not allowed to be deeply sad. Grief is a thing that we are encouraged to ‘let go of,’ to ‘move on from,’ and we are told specifically how this should be done.” Mourning feels as unnatural to her as it does to society, and even though her friends encourage her to go through the five steps (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance), it only seems to heighten her anxiety. The consolation she receives doesn’t seem to comfort her at all, as others try to relate to her loss. She explains, “After my mother died, everyone I knew wanted to tell me either about the worst breakup they’d had or all the people they’d known who’d died. I listened to a long, traumatic story about a girlfriend who suddenly moved to Ohio, and to stories of grandfathers and old friends and people who lived down the block who were no longer among us. Rarely was this helpful.” It is interesting to think that while one’s friends and family may try to relate with the best of intentions, comparing breakups to deeply impactful deaths hardly get to the magnitude of the experience.

Cheryl Strayed

By using sex as an outlet for her grief, she attempts to pacify it, which only exacerbates the main problem. That is, she can’t accept that she can go on living without her mother. She runs from emotional attachment, possibly as a way to protect herself. “I did not deny,” she says, “I did not get angry. I didn’t bargain, become depressed, or accept. I fucked. I sucked… The people I messed around with did not have names; they had titles: the Prematurely Graying Wilderness Guide, the Technically Still a Virgin Mexican Teenager, the Formerly Gay Organic Farmer, the Quietly Perverse Poet, the Failing but Still Trying Massage Therapist, the Terribly Large Texas Bull Rider, the Recently Unemployed Graduate of Juilliard… With them, I was not in mourning; I wasn’t even me. I was happy and sexy and impetuous and fun. I was wild and enigmatic and terrifically good in bed.”

This brave confession raises a number of questions, perhaps the most implied being: why is it so awful to be sad? Why should it be socially unacceptable to submit oneself entirely to their sadness and be absorbed by it? Isn’t that required of us to move on? And if we’ve already accepted that, that being deeply sad is a part of the process, why can’t we put it into practice? Not to say that Strayed’s choices are the direct result of American culture’s expectations, but who’s to say they didn’t affect her at all? Maybe it is time for us to ask these questions and take a hard look at how we want our relationship with loss to be. The avoidance, the distaste for genuine sadness, the rejection of overwhelming emotions—these are the concerns Strayed points to in a direct and honest way that, like most of life’s challenges, provide more questions than answers.

To read Cheryl Strayed’s insightful essay, go to: http://www.thesunmagazine.org/issues/321/the_love_of_my_life

And for more, check out her memoir, WILD, coming out in March 2012, http://www.cherylstrayed.com/works.htm

Looking at the essay, “The Love of My Life” by Cheryl Strayed

Looking at the essay, “The Love of My Life” by Cheryl Strayed

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?