The terrain of grief and loss is challenging enough on its own. But when a loved one’s death is shrouded in trauma, these emotional regions can remain long unexplored, as though obscured by thick fog. In “Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir,” former U.S. poet laureate Natasha Trethewey revisits memories of her mother, who was murdered by her stepfather in Atlanta when Trethewey was 19 years old. And to do so, she must part the clouds of forgetfulness that have protected her all these years:

The terrain of grief and loss is challenging enough on its own. But when a loved one’s death is shrouded in trauma, these emotional regions can remain long unexplored, as though obscured by thick fog. In “Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir,” former U.S. poet laureate Natasha Trethewey revisits memories of her mother, who was murdered by her stepfather in Atlanta when Trethewey was 19 years old. And to do so, she must part the clouds of forgetfulness that have protected her all these years:

Even when I was trying to bury the past, there were moments from those lost years that kept coming back, rising to mind unbidden. Those memories – some intrusive, some lovely – now seem to have grander significance, like signposts on a path. It’s a path I can see now only because I have followed it backward.”

“Memorial Drive” begins with an exploration of Trethewey’s racial background as the daughter of a Black mother and white father growing up in Mississippi, along with all the tension that entailed. After her parents divorced, Trethewey and her mother moved to Atlanta, where her mother met and married a character named Joel, whom Trethewey referred to as “Big Joe.” Trethewey knew from the beginning that Big Joe was trouble — a sense that, as time went on, morphed into reality:

I can’t help asking myself whether her death was the price of my inexplicable silence. I remember believing that I was a good child, that I was good because I did not complain, that I could suffer through my own trials and protect my mother from the difficult knowledge of how her life with a new husband was affecting me.

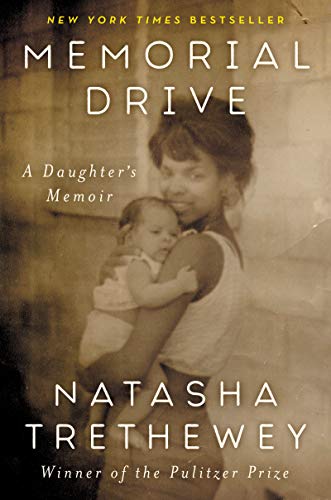

“Memorial Drive” Reclaims Time Lost to Forgetfulness

Natasha Trethewey

Credit: Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences, Northwestern University

Trethewey’s mother stayed with Joel for 10 years, during which Trethewey suffered ongoing emotional abuse in addition to her mother’s regular beatings. After Trethewey’s mother left Joel, he tried to kill her and was imprisoned. But as soon as he was released, Joel vowed to finish the job. The district attorney caught him making threats on tape and issued an arrest warrant, but due to a failure of police protection, he entered Trethewey’s mother’s apartment, shooting her twice in the face and neck.

The story is both uniquely tragic and far too common; the patterns of Joel’s behavior, unsettlingly predictable. The sense of emotional distance that predominates throughout the narrative — perhaps, the only way to tell such a story — collapses when an assistant district attorney recognizes Trethewey as an adult and hands over the file of evidence in her mother’s case — including a diary and telephone transcripts. He had been the first policeman on the murder scene, and he breaks down weeping in a restaurant — one of the few expressions of raw emotion in a story in which the characters depended on stoicism and repression to survive. Later, when Trethewey manages to go through the boxes, she has her own emotional breakthrough, collapsing on the floor and wailing in anguish.

Trethewey’s memoir may be helpful for those who have yet to face their own trauma or come to terms with a challenging aspect of their past. Even those who have not suffered so dramatically are likely to have experienced some childhood trauma — 61% percent of U.S. adults report at least one adverse childhood experience, potentially contributing to major health issues in adulthood. It’s possible that those who’ve recently suffered a traumatic loss could find themselves retraumatized by “Memorial Drive.” But for those who are ready, it may offer just the right combination of inspiration, courage and hope.

“Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir” by Natasha Trethewey

“Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir” by Natasha Trethewey

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition