Dave Eggers is something of a San Francisco hometown hero, if literary figures can be heroes. His novels, including A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, are well-known and critically-acclaimed. He founded McSweeney’s, a publishing house with a respected quarterly literary journal. And he cofounded 826 Valencia, a nonprofit organization helping underserved youth to develop their writing skills, which now has branches throughout the country.

Dave Eggers is something of a San Francisco hometown hero, if literary figures can be heroes. His novels, including A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, are well-known and critically-acclaimed. He founded McSweeney’s, a publishing house with a respected quarterly literary journal. And he cofounded 826 Valencia, a nonprofit organization helping underserved youth to develop their writing skills, which now has branches throughout the country.

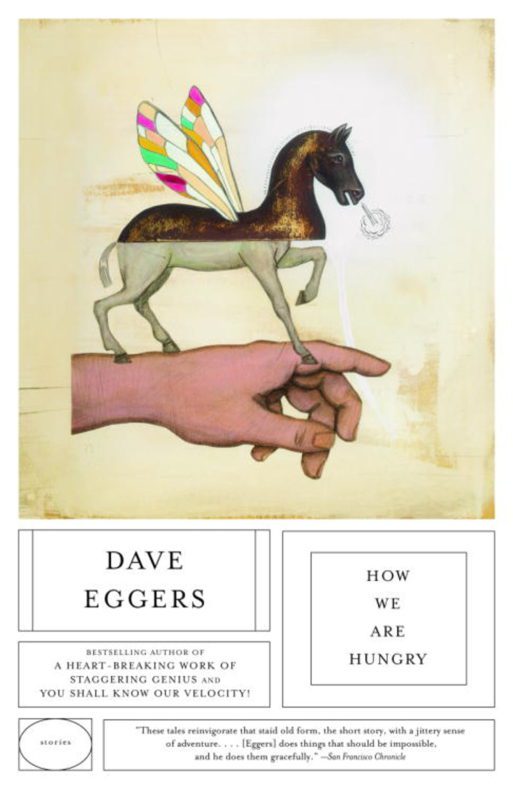

I happened to be introducing myself to Eggers, literarily, by reading his 2004 short story collection How We Are Hungry, when I stumbled across this lovely and poignant little narrative. “Notes for a Story of a Man who Will Not Die Alone” is structured as a story outline, a brainstorm, to eventually be developed into an actual story (though, implicitly, this will never happen). Eggers breaks the so-called “fourth wall” by allowing the reader into his thought process in developing this story. It might be possible to make a statement about the power of fiction that this fiction still draws us in and that the (so obviously) fictional main character is so sympathetic.

Regardless of its form, however, I wanted to share the beauty of this little story that Eggars conceived. It is about a man (Eggers cycles through a few names before deciding, emphatically, on “Basil”) who has a terminal illness and knows he will die in a few months. As the title relates, he does not want to die alone. He wants to be surrounded by as many people as possible. He wants his death to be a beautiful event, not a quiet exit in a private room.

Most of his family is confounded by this idea. But he manages to enlist the help of his son and his old friend, an event planner named Helen. The three of them meticulously prepare for the event, cycling through venues, enlisting entertainment, deciding how they will draw a crowd. At one point, Eggers tells us, Basil will give up, overwhelmed by the whole idea. But slowly, he returns to making his plan. It’s important to him, and he is fortunate in having the support of two very loving people.

When we get to the event itself, we learn they have settled on a minor league ballpark. They have recruited a local orchestra to play Basil’s favorite songs: classical pieces, the Raiders of the Lost Ark theme. There are fireworks. The grandstands are filled with well-wishers who simply arrived to see Basil off. For a moment, Helen worries that Basil will not want to leave:

“What have we done? she wonders. He is staring now at a group of men and women who have brought babies. He loves babies and he’ll want to stay forever now; this is bliss, how can he pass from this? She begins to see the point in dying alone, in cold spare rooms in hospitals in suburbs– these rooms would not be missed, making the transition so much easier…”

Fortunately, Helen is proven wrong. As Basil is “reverberating from this world to the next,” he is content. “…he is ready.”

This story is timely, as we witness the ushering in of a new era of end-of-life ceremonies in which the emphasis is on celebration rather than mourning. Though it’s not as common to hold a celebration at the exact moment of transition, as Basil does, end-of-life celebrations, in which a terminally ill person is present for a joyful ceremony with family and friends, are growing in popularity. Even after-death ceremonies increasingly take on a party-like atmosphere in a way that celebrates the life of the one who passed while also serving the healing needs of the ones left behind.

Eggers’ short story illustrates this new attitude toward death– as transition rather than ending– and his poignant death ceremony, though fictional, reminds us of the possibilities of life.

“Notes for a Story of a Man who Will Not Die Alone,” by Dave Eggers

“Notes for a Story of a Man who Will Not Die Alone,” by Dave Eggers

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull