What if researchers discovered a cure for cancer, but in the process, unwittingly triggered a deadly genetic disease? This is the premise behind “The Evening and the Morning and the Night,” a short science fiction story by Octavia Butler. Although the disease in her story is fictional, Butler touches on real themes and issues that impact our society today, showing us in great detail what it’s like to live with a terminal illness, and how isolating it can be.

What if researchers discovered a cure for cancer, but in the process, unwittingly triggered a deadly genetic disease? This is the premise behind “The Evening and the Morning and the Night,” a short science fiction story by Octavia Butler. Although the disease in her story is fictional, Butler touches on real themes and issues that impact our society today, showing us in great detail what it’s like to live with a terminal illness, and how isolating it can be.

In “The Evening and the Morning and the Night,” we follow the main character, Lynn, as she describes what it’s like to live with the fictional genetic disease, Duryea-Gode Disease, or DGD for short. In Butler’s fictional world, doctors recently invented a drug that’s capable of curing cancer. However, they later discover that the drug has an unexpected side effect: It causes a genetic mutation in those who take it, which is then passed on to that person’s future children. The resulting genetic disease, DGD, causes psychosis at first, but as it progresses, those who have it begin to act out violently against others and commit self-mutilation. In nearly everyone who has DGD, the disease is ultimately fatal.

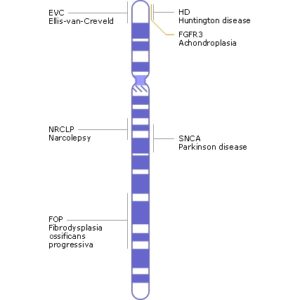

While DGD doesn’t actually exist outside of the novelette, Butler draws inspiration from real genetic diseases, including Huntington’s disease, phenylketonuria and Lesch-Nyhan syndrome. Because her invented disease so strongly resembles these three real conditions, her characters think and behave just as a real person with a terminal illness would. In this way, “The Evening and the Morning and the Night” can teach us what it’s like to face death at such a young age, and how those with terminal illnesses support one another and cope, even as they’re isolated from the rest of society.

Exploring Social Stigmas

Butler drew inspiration from genetic diseases like Huntington’s disease for her short story

Credit: wikimedia.org

The short story’s strongest theme is that feeling of isolation. Because DGD is a violent and dangerous illness in “The Evening and the Morning and the Night,” those who have it need to wear a pendant around their necks signaling to others that they are DGD-positive. As a result, the protagonist feels cut off from most of the people around her. They either keep their distance from her or act guarded in her presence. Lynn finds more comfort in her peers who also have DGD. She lives in a small house with a group of other college students who have the disease. They feel as though they can understand each other.

Here, Butler draws significant inspiration from the treatment of both people with mental illness and AIDS patients in the 1980s. When the HIV virus first appeared in the United States, many people were in a panic and treated people who were HIV-positive as pariahs in the community. In some cases, patients would gather together in community housing to support one another through their illness, even as mainstream society shunned them.

The Loss of Autonomy

Butler shows us how important it is to feel accepted by a community, especially when coping with a terminal illness. But as the short story approaches its final scene, we see her character grapple with even more of life’s milestones that many of us take for granted.

For instance, the main character, Lynn, realizes that she will never be able to have children because she’ll risk passing the disease on to them. Lynn herself is the product of two parents with DGD (both of whom died when she was a teenager). And she feels conflicted about their decision to have her. This feeling is relatively common among those who have a terminal genetic disease.

Credit: af.mil

Lynn also feels as though she has no control over her own body or her destiny. Early in the novelette, she knows that eventually she will die at a young age, likely violently and painfully by her own hand. But later in the story, she feels the need to help others cope with the disease rather than following her own aspirations. She loses her sense of autonomy and individuality in the process.

The subtle irony of “The Evening and the Morning and the Night” is that a cure that was supposed to extend the quality of life for cancer patients in fact led to a worse terminal illness that spreads across generations. Yet Butler reminds us that even of we’re facing insurmountable odds, we can still squeeze as much life and joy as we can out of the little time we have.

“The Evening and the Morning and the Night” by Octavia Butler

“The Evening and the Morning and the Night” by Octavia Butler

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?