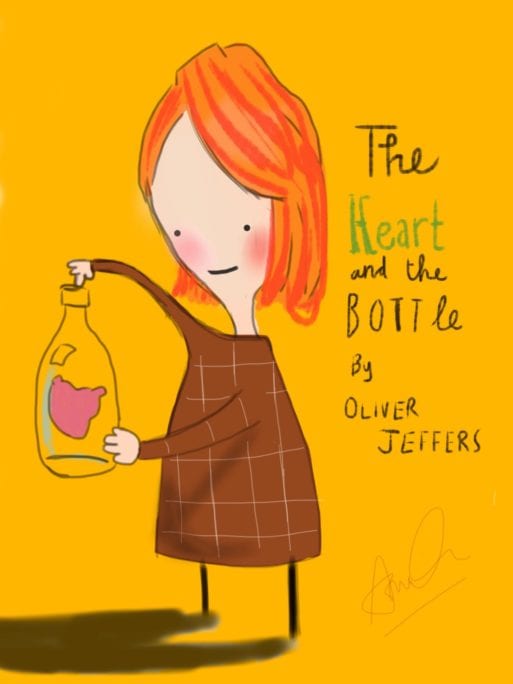

“The Heart and the Bottle” is a lovely, beautifully illustrated fable about a young girl grappling with loss and grief. Written and illustrated by acclaimed artist and children’s book author Oliver Jeffers, it is a simple story of a young girl whose “head is filled with all the curiosities of the world.” She shares that world with a man — presumably her father — who sits in a big red chair and reads her books about every subject imaginable. He also shares in her real-life adventures as she explores the mysteries of the stars and the wonders of the sea. She’s a happy little girl, “much like any other.” Until one day she finds her father’s chair empty, and she is crushed.

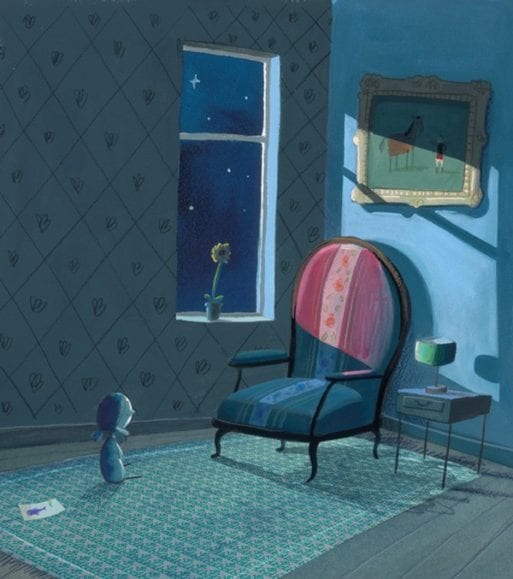

Not sure what to do with her grief, the girl decides the best thing is to take her heart out of her chest and store it somewhere safe. And so she puts it in a bottle — just for a little while — and hangs it around her neck. And while this seems to help, she finds that nothing in her life is quite the same. She has lost her curiosity and her capacity for joy. And as she grows into a young woman, the bottle around her neck becomes more awkward and heavy, even as thoughts of the empty chair still fill her head.

Eventually, the young woman meets a little girl who asks her questions about life’s curiosities, just as she once asked them herself. But the woman can’t answer her because her heart is still locked away in a bottle around her neck. She decides, then and there, to take her heart out of the bottle again. But she discovers that the bottle is too strong.

But then something amazing happens. Just as the woman gives up, the little girl takes her tiny hand and reaches into the bottle and pulls out the heart. She gives it back to the woman. And just like that, “the chair wasn’t so empty anymore.”

Jeffers tells the young woman’s story in pictures far more than in words. Early on, there are glorious illustrations of a world bursting with wonderful things and ideas to explore, followed by a crushing image of a young girl confronting the reality of her father’s empty chair. Later, we see pictures of a young woman very much alone in the world as she eats a solitary meal, the heart and the bottle hanging heavy around her neck. But when her new acquaintance finally manages to free her heart, the final image of the young woman sitting in her father’s chair reading the books she once loved lets us know that the woman, too, has been set free.

The symbolism in “The Heart and the Bottle” is, of course, obvious. Burdened by grief that she couldn’t express, the little girl grew up to be a joyless young woman still haunted by the memories of the father she lost. By trying to protect her heart from pain, she had also protected it from everything beautiful and wonderful about the world. Worse yet, when she finally realized what she had done, it was too late to set it free.

At least not without help.

Recommended by Publisher’s Weekly for children aged four and up, “The Heart and the Bottle” might be a bit too nuanced for young children to grasp without a fair amount of explanation from an adult. Although I haven’t had the experience, I can imagine that a child of four or five might wonder how the young girl got her heart out of her chest and why she needed to keep it safe. But I also imagine that their confusion would be a great opportunity for an adult to talk about why it’s important to be honest about our feelings, even when they are painful, instead of locking them away.

All in all, “The Heart and the Bottle” is a charming children’s story that deals with grief and sorrow in a touching and unique way. The illustrations are beautiful, and the take- home message — that even broken hearts can heal — is one every child needs to hear again and again.

“The Heart and the Bottle” by Oliver Jeffers

“The Heart and the Bottle” by Oliver Jeffers

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One