This is Joseph’s story as told to Cara Olexa. Our “Opening Our Hearts” stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and, ultimately, to aid them in their healing process. In this story, Joseph talks about losing his father to dementia while Joseph was still a teenager, and how the behavior of his siblings after his father’s death compounded his loss and grief.

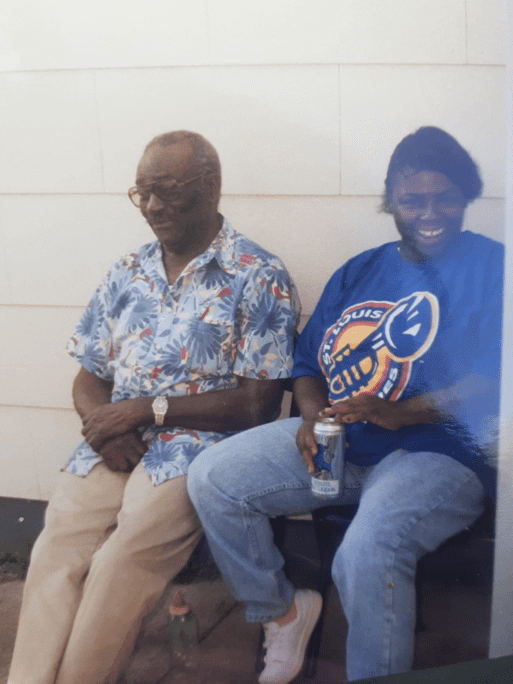

A picture of a picture of my father and mother on vacation in the 1990s, when they were still together. They’re both gone now, and so is the original photo. My older brothers and sisters took the family photo albums after my father died.

When I was just 16 years old, my father died from a stroke after struggling with dementia for years. I was just a kid, and his dying was really hard on me. I’m 28 now and still don’t have all the words to describe it. But then I lost him again when my siblings told me at his funeral that I wasn’t his “real” son and sent me and my mother to sit in the back of the church.

In some ways, I never had all of my father to begin with. He was in his 70s when I was born, and he’d had a whole other family before I came along. There was a big age difference between him and my mother, too, and that impacted everything. I had brothers and sisters my mother’s age. You can imagine what they probably said about my mother when my parents first got together.

My father loved me, but even when I was a young kid, I sensed that he wasn’t willing to give himself over completely to raising another child. Like, he’d done that once already. I probably picked up on whatever was going on between him and my mother too. I know they loved each other, but something made them split up. But even after that, they stayed close. It about killed my mother when he died.

My father used to go on these hunting and fishing trips down to Alabama. I remember I wanted to go with him so bad. Every time, before he left, he’d take me out to Salt Creek Woods, out in the western suburbs, so I could dig up worms for fishing. I’d dig up all these worms and put them in an empty soup can for him. Every time, I waited for him to ask me to go with him, but he didn’t. I’m sure he knew I wanted to go. But I think going to Alabama was some kind of getaway for him.

Still, every place I went when I was little, my dad took me. It was always him and me together, going to the video store, to Game Crazy, the barber shop, driving all over town. I’d think of a place I wanted to go, and he’d put gas in the car and we’d go.

School was dangerous, and my neighborhood was full of people who had lost somebody to violence or were afraid they would.

I was my mother’s only child, so I pretty much was an only child, because all my brothers and sisters were so much older than me. I was alone a lot and didn’t have any close friends. School was dangerous, and my neighborhood was full of people who had lost somebody to violence or were afraid they would. A lot of folks were poor, and that makes everything harder. It was like trauma was in the air, and everybody you saw was breathing it in and out all the time. People had to rely on relationships with family and friends to get through the hard parts. My childhood was really hard, and I needed more family in my life, not less.

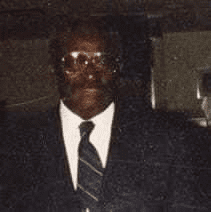

A rare photo of my father all dressed up, probably at church. His hair’s not gray in this picture, so I can tell it was taken before I was born.

My and I father watched a lot of TV together even before he got sick. He loved WWE. He knew all the moves, the history and backstory of every wrestler, who fought who for what belt, all of that. We’d go to the live shows whenever they came to Chicago. But after he got sick, it got harder for him to move around, so mostly we just watched TV. He’d put on wrestling and tell me about everybody all the way back to the 1980s, like Hulk Hogan and Andre the Giant.

I liked wrestling but didn’t love it, but he got so excited every time he talked about it. I knew if I made myself love wrestling, he’d talk with me even more, and he’d just be happier. So I made myself love it. I still love it to this day.

My father’s dementia started kicking in when I was 14 or 15. He was losing touch with where he was and having trouble paying the bills on the house, stuff like that. He was so sad and angry sometimes. Usually not around me, but I could feel those feelings kicking around in him. He’d been a successful construction worker, a strong man who people leaned on. He was proud of his house. He’d paid it off, and he’d always kept it up, did all the home repairs, kept the lawn nice. I think he was ashamed that suddenly he was doing things like forgetting to pay the water bill. Sometimes I’d go over there and see a week or two of mail piled up on the kitchen table.

He was suddenly in this vulnerable position in every way. He had trouble doing things like getting dressed, and he’d go outside without his shoes on.

Eventually his sons and daughters had to step in and help him manage the bills and stuff. It made him mad that they had started making all his decisions for him. I’d hear him on the phone to my mother, yelling about it. He started drinking, too. He never used to get drunk like that, but he was trying to cope with the stress, I guess. He was suddenly in this vulnerable position in every way. He had trouble doing things like getting dressed, and he’d go outside without his shoes on. He had to give control of his bank accounts to his older children too.

Later I found out one of my brothers who had control of my father’s bank accounts had taken all the money out of my college savings. It was something like $3,000. I know families do those kinds of things to each other, but I never thought it would happen in my family, to me. That could have made a difference in my life, for college or something else. I had some real hard years in my late teens and 20s. My mom died before I graduated high school, and I was homeless for a while. Three thousand dollars might not sound like much, but when you have nothing, it’s a lot.

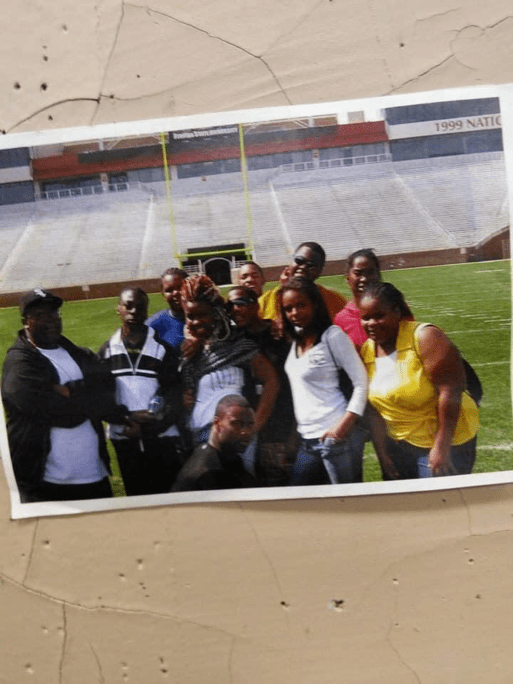

That’s me on the left in this group photo from my Upward Bound program, which helps high school students prepare for college. My UB mentors’ support helped me survive while my father was dying from dementia.

That was also around the time when my older brothers and sisters started keeping me away from my father. I still got to see him sometimes, though, to watch wrestling. One of my brothers or sisters would come to my mom’s and pick me up and take me to his house for “Monday Night Raw.” It was a really hard time for me. I was in high school, and sometimes the bullying was torture. Kids I’d known since grade school were getting killed in the streets. I had been sexually abused by my cousin when I was younger and hadn’t told anybody, and now I was a teenager and trying to deal with my own sexual feelings, and it was really hard. I’m not saying I would have told my father about that — I never was able to tell my mother — but with him so sick, it wasn’t even an option. I needed his help with growing up, but instead I was trying to take care of him while he was losing his mind. It was horrifying to see him suffering. I just tried to be there for him, to help him however I knew how.

When we watched “Monday Night Raw,” I’d ask him questions about all the wrestlers from the 1980s and 1990s, so he could talk about things he remembered. I could feel his relief when he got to talk about the Ultimate Warrior, the Bushwackers, Owen Hart, Chyna, Triple H, Stone Cold Steve Austin — things he knew he remembered, memories he could trust when all of his other memories were coming loose. I was only 16, but I did the best I could, and he knew that.

I remember one day he called my mother drunk and I heard him say, “I don’t know if Joseph is my son,” and my mother answered, “Don’t say that, don’t say that.”

It was also about that time that my father started saying things about me maybe not really being his kid. I remember one day he called my mother drunk and I heard him say, “I don’t know if Joseph is my son,” and my mother answered, “Don’t say that, don’t say that.” That was the first I ever heard about anything like that, and it freaked me out. Maybe my mother had cheated on my father back around when I was conceived, I don’t know. Things like that happen. I just never thought it would happen to me.

I think now that maybe that’s what gave my sisters and brothers the idea that I wasn’t really my father’s biological son. Maybe as he started drinking more and his dementia got worse, he started telling them that he suspected my mother of cheating on him. I don’t know. Before my father got sick, my siblings all treated me like a little brother. Whatever their first opinions of my mother were, I felt like they looked at me as part of the family. But maybe they were lying to me the whole time.

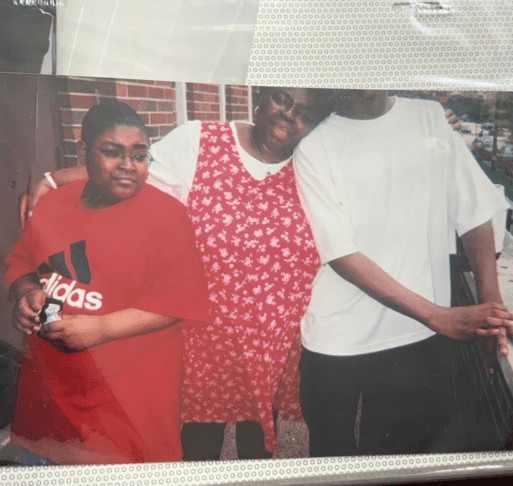

Me and my mother standing outside her friend’s house on the West Side of Chicago when I was 10 years old. She and my father had separated by this time, but they still loved each other, and she made sure he was in my life.

At some point, my father’s older children put him in a nursing home. I didn’t even know about it until after he was there. But things didn’t go well, and after a while they brought him back home. I don’t know why they thought that would be any better for him. By this point, he couldn’t take care of himself.

My father had the stroke that killed him not long after that. It was a Monday night, and one of my brothers called me and told me I needed to come over because my father wasn’t doing too well. I got there during “Monday Night Raw,” and all of my brothers and sisters were there. My father was sitting on the couch, kind of propped up with cushions, and they were standing around him. The TV was on but everybody was talking over it.

I remember my father was pleading with them, saying, “I want to go home. I want to go home.” My one brother kept saying, “You are home. This is your home.”

In the middle of all that he had a stroke. I saw it happen. I just remember him looking up at the sky. I know we were in the living room, but I knew he was seeing the sky.

My brother called an ambulance, and they came and took my father to Mt. Sinai Hospital on the West Side. I never saw him alive after that. He died early the next morning.

The day of the funeral, I knew something was wrong when my brothers and sisters didn’t ask me and my mother to get in the limo for the family ride from the funeral home to the church. Somebody gave me and my mother a ride in my dad’s car, I don’t remember who.

That’s when I saw my mother and I were listed as my father’s “friends.”

Then, when we got to the church, one of my uncles put a copy of my father’s obituary in my hand and stood there, like he was waiting for me to read it. So I did. That’s when I saw my mother and I were listed as my father’s “friends.”

I remember my confusion. Tears rolled down my face. I kept saying, “No, not today,” over and over. And, “How can you do this to me? You’re my family.”

“He’s not your father,” my one brother said, “and you’re not our family.” Then he ushered me and my mother to a pew back behind where the family was sitting. I remember a lot of what happened that day, but I don’t remember what my mother and I said to each other. Maybe we just sat there silently during the service.

I learned later that my siblings had a DNA test done, which they claimed proved I wasn’t my father’s son. But what it actually said was that the results were “inconclusive.” I didn’t know for a long time that what that meant was that they couldn’t tell one way or the other. Mostly likely there just wasn’t enough DNA on the cotton swab to run the test right.

Two years ago, I got to hold this photo of me when I was 7 years old. When I was that age, my father and I would drive all over Chicago to rent movies, buy video games, go out to eat, anything I could think of. He’d put gas in the car and say, “Alright, son, where do you want to go?” I loved it.

I don’t know what’s worse, that my world got blown up over somebody holding a cotton swab wrong, or that my older brothers and sisters think a lab test matters more than the people in your life.

The rest of the funeral service, I felt overwhelming sadness — and anger too. Anger at my brothers and sisters, but also at both my parents. But I was also just angry at the cards dealt to me. My past was something I used to hold on to, but at that moment it stopped being solid. My sense of identity disappeared, and I started falling, spinning end over end.

To this day, I still ask myself, “Who am I?” And, “If my father isn’t my father, who is?”

No matter what, though, I still have my father in my heart. And I trust that in his heart I was his son and always will be. They can’t take that away from me.

I Lost My Father Twice — Once to Dementia and Once to a Flawed DNA Test

I Lost My Father Twice — Once to Dementia and Once to a Flawed DNA Test

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull