This is Suzette’s story as told to Jeanette Summers — the story of her disenfranchised grief over discovering her husband Peter’s homosexuality. Our “Opening Our Hearts” stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and, ultimately, to aid them in their healing process. In this article, Suzette tells her personal story of experiencing disenfranchised grief after learning her husband was gay.

Peter was my husband, my companion, and my very best friend. We shared a home, a bed, and a most wonderful life for 20 years. Unbeknownst to me for all of those years, he was — and is — gay.

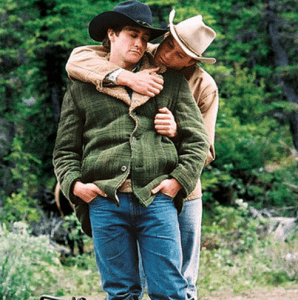

It registered in the back of my mind as odd, but I was too absorbed in the beauty of the film to pay it much attention.

When I first found out, we were living in a loft in San Francisco. We managed to get our hands on an old Epson projector for cheap. Peter and I would regularly host movie parties; all of our friends would come over to share in the magic. When we’d turn off the lights and push the play button on our DVD player, our living room would transform into a cinema — the moving picture projected onto our blank, white wall transporting us to another dimension — a broader world.

Following the circumstances of the impact of

watching the film Brokeback Mountain I would

be unable to watch a film for the next 5 years

One night, I rented the film “Brokeback Mountain.” For those who haven’t seen it, it is a film about two men who discover their sexuality together, which later results in one man’s wife discovering that her husband is gay. It was just the two of us — no party, no company — a tiny mercy, I now realize. During the scene where the two male protagonists, Ennis and Jack, finally surrender to their forbidden, carnal desires and make fierce love for the first time in their ranchers’ tent, Peter jumped — levitated — off our living room sofa. “What’s going on?” I thought peripherally. It registered in the back of my mind as odd, but I was too absorbed in the film to pay it much attention — until later that night.

After the film was over, Peter and I climbed into bed. He spooned me — holding onto me so, so tight — tighter than he ever had before. All at once, every cell in my body was screaming: I touch him every single day, I thought, the realization crashing over me like a series of shock waves, yet he stopped touching me a long time ago. In that moment, I came face-to-face with the sharpest, rudest, and most tragic epiphany of my life to date. The man I adored and trusted most in this world was — and had always been — attracted to men. When I’d woken up that morning, my husband’s homosexuality wasn’t even vaguely on my radar. And suddenly, I was 200 percent positive. There was no un-knowing it.

And suddenly, I was 200 percent positive. There was no un-knowing it.

I lay in bed, unable to sleep. The past 19 years unfurled before my eyes — a film reel unwinding from its spool. I spent the night scanning my memory, replaying scene after scene from our marriage at the speed of light. I was desperately combing for signs, hints, clues that I’d somehow overlooked: How we’d first connected through a design gallery show. How, when he avoided sex, I’d always laugh and say, “Isn’t the wife supposed to have the headache?” How could this be real? How could this be happening to us? How could I have missed it? Did everyone in my life, except me, see the truth that my husband was gay — the truth about our marriage?

Our beautiful wedding at Mohonk Mountain House in New Paltz, NY will

always be the happiest day of my life.

The next morning, I woke up determined to tell someone, and I instantly thought of my gay neighbor. I’ll talk to him tomorrow, I thought. I said this to myself every day for weeks — an endless succession of tomorrows, until finally, I realized that tomorrow was never going to arrive. I would keep it quiet. I would let it fade until it disappeared. I was in a deep state of shock. Unbeknownst to me, I was suffering disenfranchised grief, a shattering grief that society fails to recognize.

I was in a deep state of shock. Unbeknown to me I was suffering disenfranchised grief, a shattering grief that society fails to recognize.

Peter and I continued to live together for the next year, but I barely touched him. I mentally pushed him away until finally, I told him he had to move out. At this point, we still hadn’t addressed his sexuality; I still hadn’t discussed his being gay or told him that I knew. A few times I wove the word “gay” into our everyday conversation as seamlessly as I could, trying to gauge his response, but Peter remained non-reactive — cool as could be.

We remained in touch after the separation. I still loved him, after all. In fact, he moved two short blocks away to a place I’d helped him find; by a fluke, I could see his front door from my front door.

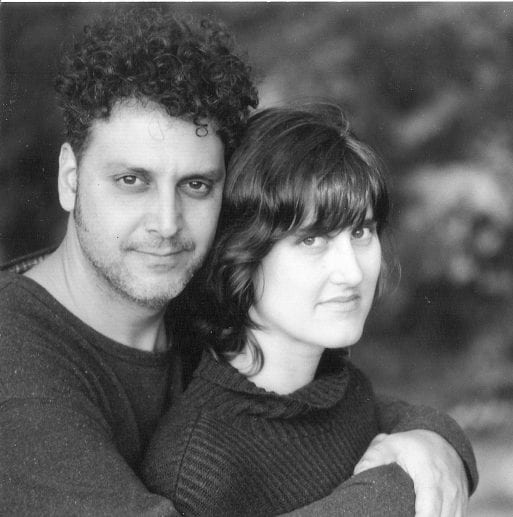

After all these years, this is still my favorite

photos of him, which I shot while on a road trip

— heart strings last a lifetime

Despite my deep, unacknowledged grief, one day — three years after we’d separated — I marched over to his studio. I’d decided to confront him once and for all — calmly and gently but directly, at last. I remember delivering a well-rehearsed monologue that concluded with the words, “You’re gay.” He neither confirmed nor denied it. He simply deflected, redirected, threw up a smokescreen and screamed, “I don’t have time for this!”

I remember another occasion after the separation when Peter stopped by to check on me. He still cared for me deeply, and he wanted to know I was okay.

“I’m worried about you,” he said.

“I’m worried about you,” I said.

I had reason to worry, but truthfully, so did Peter. After all, we’d both experienced a loss that had left us shaken, upside-down, inside-out — even if no one on the outside could see our disenfranchised grief.

For a while, I actually told people, “My husband is dead.” Some found this absolutely appalling.

Some people’s grief is a violent explosion; mine was a small, private room. One — much like the closet Peter had locked himself in — that no one knew about, let alone entered, for a long, long time. I was in a state of disenfranchised shock. My pain was searing — bone-deep — but silent as the dead. Unheard and unacknowledged. Internally, I was shrieking constantly.

A selfie during those incredibly difficult years

of emotional pain, nervous breakdowns and

crying jags

I was in mourning for years. For the first two, I was what I now call “The Walking Dead.” For the following two, I experienced uncontrollable crying jags. For a while, I actually told people, “My husband is dead.” Some found this absolutely appalling. But in truth, my marriage was over. My life was irrevocably altered. My husband, as I knew him, was dead. When a widow loses her husband to a physical death, her loved ones flock to her side. They rock her. They feed her. They hold her to their breasts and absorb her tears and muffled animal groans into their sweaters. But how could I expect people to understand this? There is a reason they call it unacknowledged grief of the most isolated kind.

Could I survive this grief? This unbearable loneliness?

I could. And as it turns out, I did.

I’m still very much alive; I’ve even started dating again. Peter is very much alive, too. Since our separation, he’s come out to his traditional, conservative Greek family. He did say the words “I’m gay” aloud. I still talk to him on the phone at least every couple of days. We trade business tips, vacation homes. But as someone who reserves her affection for romantic relationships, I can’t touch Peter anymore. No cuddling. Certainly no kissing. Not even the quickest and most cursory of hugs.

Matter can’t be created or destroyed, only transformed into other matter. Peter and I remain present for each other, albeit in a very different capacity: as friends, sometimes even as confidantes, but no longer as partners. Our relationship as husband and wife has died, but it’s been reincarnated into the deepest and truest friendship I’ve ever known — one that’s endured more than I imagined any relationship could.

Peter, as my husband, may be dead to me. But Peter, as a human being, is not. I love Peter, and I always will.

My Disenfranchised Grief When I Discovered My Husband Is Gay

My Disenfranchised Grief When I Discovered My Husband Is Gay

Terminal Sedation at the End of Life

Terminal Sedation at the End of Life

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!