My beautiful grandmother at 16 years old

This is Irena Kaci’s story as told by herself. Our Opening Our Hearts stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and, ultimately, to aid them in their healing process. In this story, Irena Kaci tells the story of her grandmother’s sudden death overseas and the ways in which it shaped her adult self.

To tell the story of my grandmother’s death, I must first tell you the story of my life. I came upon her toward her later years. She would’ve been around 52 years old when I was born, but her age was immaterial to me at the time. She was the warm matriarch of my earliest memories, and age just didn’t figure into it.

So my grandmother was a kind of first mother to me.

My parents had a difficult life; though they were not unique in their circumstances under the Hoxha regime. It was customary for grandparents to have a very hands-on role in (grand) child rearing. So my grandmother was a kind of first mother to me. She was the face I searched for in crowds, the backbone of our home, and in every way, the center of my – albeit tiny – universe.

The household I grew up in consisted of myself and my two sisters (both older and younger), my grandmother’s children, a string of never-to-be-married aunts, and a soon-to-be married uncle, along with his wife and eventual children. What the household was missing, of course, were my parents. They lived in a distant northern city and visited sporadically. It was chaotic, and ever shifting, but it was my home. And while my grandmother was in it, it felt like a good one.

From left to right: my mom, older sister, grandmother, and me, as a baby

But during the late-stage communism of their lives, their singleness was a terrible cross to bear.

The unmarried aunts might’ve been deemed heroines, powerful and interesting women, each with their own stories and ambitions in another Albania, perhaps a generation or two removed. But during the late-stage communism of their lives, their singleness was a terrible cross to bear, one that grew heavier with the added burden of someone else’s brood always about. And though I didn’t quite understand the extent to which we were an imposition, I experienced their daily ambivalence toward me.

As is the way with many big families, everyone had a niche. Once family members depart the nest, they take on different roles in different relationships, thereby developing a more well-rounded sense of self. However, without that launching into the world, roles can fester, and the sense of self never fully develops, hardening instead into a caricature of what might’ve been.

In that family, I took on the role of the liar and the rebel. I was well suited for it: I lied poorly, getting caught in flimsy lies, and therefore reliably offering myself as an easy target. I was obstinate too, and persisted in doing things my own way, providing a flamboyant contrast to my elder’s sister dutiful obedience. So it was settled, long before I started elementary school, that I was up to no good.

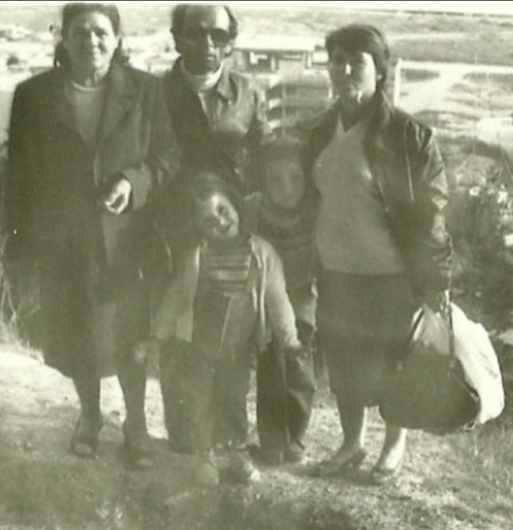

From left to right: my grandmother, my uncle, older sister, and oldest aunt; then me in the front

As any scapegoat, I got the lion’s share of blame, punishment and disapprobation. And once I gained any type of agency over it, I leaned into the freedom of doing what I wanted, flaunting my own sense of self, and using conflict to develop my own reason and judgment.

My mother would show flickers of admiration for me here and there, but did not quite take to me the way that my grandmother did. My grandmother’s kindness was steadfast, whereas my mother’s was unreliable. Often cowed by her sisters, my mother would only betray her bemusement with what she dubbed “my general spirit” in private settings. I treasured that muted victory, but could not have borne childhood without my grandmother’s unwavering affection. In the sea of exasperated adults, my grandmother was the only one who showed me any true kindness.

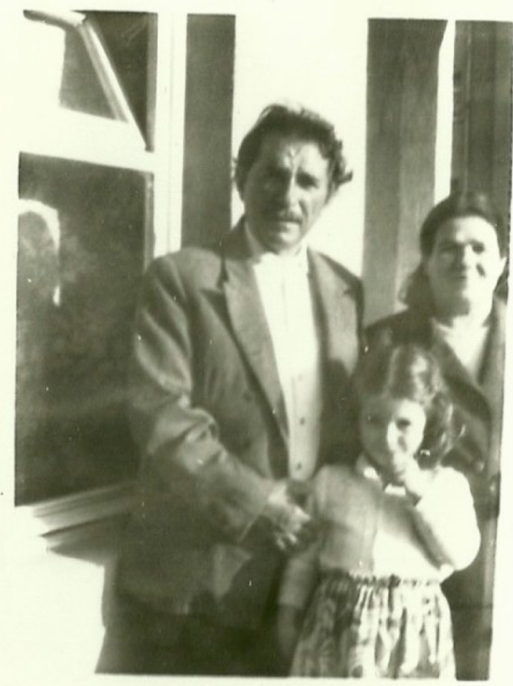

My grandpa, grandma, and me circa ’89/’90

My mother had won the visa lottery to go live in America.

When I was 12 years old, communism’s embers were starting to catch fire in Albania, and there was talk of civil war. My parents, having moved to my mother’s hometown a few years back, found yet another opportunity for relocation. My mother had won the visa lottery to go live in America. Had it not been for the impending political turmoil, my dad might’ve tanked the whole plan, but ultimately my mother had her way. Two months after winning the lottery, we were suddenly a family of only five all the way across the ocean.

It is impossible to enumerate the losses I felt during those first years. Short of space travel, nothing else can quite capture the sense of lonesomeness borne out of not just leaving my country, my language, and the only home I had ever known, but also my grandmother. My parents were relative strangers to me, and they were never around, first always looking for work, and then always working. I had been forced to abandon everything, including myself — that small Albanian 12-year-old whose whole imagined future had been replaced with something cold and incomprehensible.

I missed my grandmother; I missed her the way I assumed people missed their mothers. I wanted to be near her, to be in her orbit, to have her feed me and fuss over me, to have her voice soften the disapprobation of the other adults around me, to feel the comfort of her drooping head asleep on her corner of the sofa while the living room TV played spaghetti westerns.

My grandma and grandpa on their bedroom’s balcony

Two years later, my parents scraped up enough money to plan a visit. It was the summer of ’98, arguably the peak era of conflict in my country. I was a budding adult, well into my teens, and I leaned into rekindling old friendships, navigating my old haunts, eschewing most of the family time for the adventures of my peers. And though it was unthinkable that it was my “last time” for anything at that age, I do remember climbing into the taxi that was taking us back to the airport with unresolved feelings. I stared up at my grandmother’s shining, benevolent face waving goodbye until the building fell out of sight, wishing I could look at it again and again.

My grandma, surrounded by her next generation of grandchildren during the late ’90s

I did not then appreciate that I would not return for another five years. Y2K came and went; we somehow bought a house and moved to a small suburb of Hartford, and I transferred to a new high school. My older sister was off to college and struggling with suicidal thoughts, and I had entered the awkward age of feeling ashamed about everything. All five of us were going full speed in opposite directions, somehow even less connected than when we had arrived. It was November of my junior year of high school.

My Algebra II teacher had assigned us a project involving math and cookies. I spent my Algebra II class period reading novels, so the details were foggy all along, but one thing penetrated even my distracted consciousness: no late projects would be accepted, no matter the circumstances. This project was due on Monday, November 20 and not a minute after. I had naturally decided to tackle the whole thing the weekend before, and of course the weekend became actually the Sunday before.

The phone rang, and, welcoming the distraction, I sprang for it.

That Sunday my parents’ closest friends had come over for the big meal of the day, which is a mid-day meal. Both couples sat across from one another in the living room table, having appetizers, with only my mother getting up from time to time to serve little glass dish after little glass dish of Albanian tapas. I was working on my math project in what we called ‘the computer room,’ which was right next to the living room. The phone rang, and, welcoming the distraction, I sprang for it. On the other end, my second uncle spoke curtly, asking for my mother. I was impressed with myself for recognizing his voice, and correctly identifying him to my parents as I handed over the receiver.

Left to right: my dad, mom, grandma and grandpa during the summer visit in ’98

It’s remarkable how much is communicated by things other than words. I remember knowing then — even without being able to think it, even without any concrete reason to think it — that my grandmother had died. I held my breath, anticipating my mother’s cries, and burst into tears with her when they came.

We were all suddenly stuck in this brittle house of grief, not being able to comfort one another. My parents were still relative strangers to me, to all of us. Maybe they thought we were too young to be affected. Or maybe they didn’t think about us at all. My mother was the focus of the loss, almost understandably. It was fortuitous that close friends were nearby as they were able to quickly make travel and childcare arrangements. Only my mother could afford to go, so upon losing my grandmother, I was to temporarily lose also my mother. The house felt empty, bereft.

I started to unravel from whatever center held me together. My little sister simply sat nearby and let the storm pass. I remember terror like I had never felt before, like the trauma of immigration had suddenly hardened into the end of the world. I thought maybe I could cope with being so far away from my life if I imagined it as static, as a place I could continue to visit, a place untouched by time.

My grandma in her best suit and wearing her signature bag, during the early ’90s

I remember vowing to never be thankful again, a vow which I have now broken many times, and gladly.

I never did complete the cookie project. I remember screaming and bursting into sobs when pressed on my ‘reasons,’ not that I cared to explain myself. Nothing comforted me, and the few administrators who even learned of my loss and attempted to help were so far outmatched by the scope of my rage and grief that they failed and fled.

It was Thanksgiving week, which felt mocking, and I remember vowing to never be thankful again, a vow which I have now broken many times, and gladly. My grandmother’s death was life-defining for me at 16; it was my first encounter with the incredible finality of death and its aftermath, the place where terror meets grief.

I made my way back to normalcy over many years, but the brunt of the work happened that winter. I turned to what had always been there for me: literature. I have always been a reader, but in the remainder of that school year, I made my way through the bulk of American poetry, reading through the cathartic and sometimes macabre works of Millay, Plath, Dickinson, and Sexton. I threw myself into memorizing long epic poems, chanting them in my head like spells steadying my footsteps, like talismans keeping me safe.

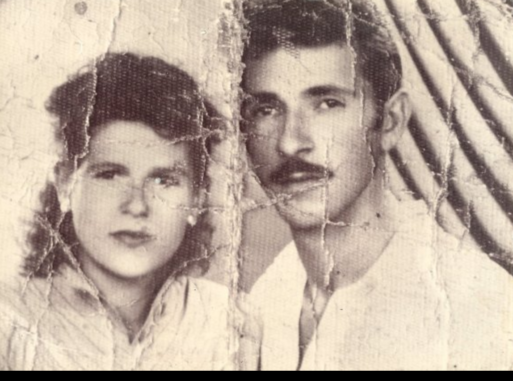

A picture taken during the early phase of my grandparents’ courtship

During college, my grief would herald every coming November, swelling with each passing day, until it overwhelmed me. I didn’t notice the effect receding until well after college. The first time I didn’t experience any part of this cycle, I cried tears of guilt instead.

Now my grandmother has been gone for over two decades, and when November returns, I welcome her memory. The sting of loss is pleasurable, like a sunburn. Some mornings when I am swimming laps at the local pool, I imagine my grandmother on her deathbed. I see her lying down and thinking of everyone she loves, thinking of me, and I imagine all that love – once trapped in her delicate frame – releasing.

My Grandmother’s Death Tore My Life Apart

My Grandmother’s Death Tore My Life Apart

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition