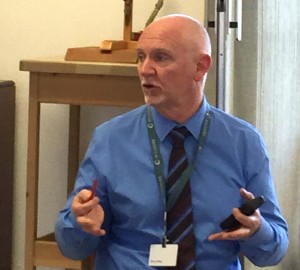

Steven Willey began his hospice career in 1995 as a volunteer and home health aide for San Luis Obispo County Home Health and Hospice. In 1997, he became Volunteer Coordinator for Hospice of San Luis Obispo County, where he remained until joining Wilshire Hospice in 2011. Steve has degrees in both psychology and social sciences and completed the “Sacred Art of Dying” course at the Sacred Art of Living Center in Oregon. In 2001, he helped found the Supportive Care Services Program at the California Men’s Colony, which trains inmates to provide compassionate end-of-life support for fellow inmates. His role at Wilshire Hospice includes the training, supervision and nurturing of hospice volunteers.

Carla: What originally inspired you to work within the field of death & dying?

Steven: I came to work accidentally, hoping it would give me tools I needed when I was left alone in the hospital with patients who’d passed. I wanted to feel more skilled when interacting with the families. One night, watching a video about ‘Healing Touch,’ the thing that spoke to me was seeing a nurse sitting with a dying patient. Here was a person who was just sitting with a dying person. She was brave enough and compassionate enough to just sit there. This has colored everything since I began. Everything is about presence, first and foremost, no matter what your role is within the hospice team.

Carla: Death is tricky. Everyone moves toward death differently and processes grief in ways that are unpredictable. Sometimes there is love and peacefulness; sometimes anger, distancing, argument. What qualities within yourself did you cultivate in order to become skillful and present under difficult circumstances?

Steven: For me, the ability to acknowledge and let go of what I can’t change is crucial (and very comforting). Harder, but as important, is being non-judgmental both of others and myself…as in judging my limitations. I work all the time at being invested in my intentions more than in their outcomes. I believe if the good or positive intention is there, most of the time the outcome will be good whether I actually see it or not.

Carla: Is hospice training standardized throughout the industry? How did you decide on the particular curriculum you teach?

Steven: There are certain topics that must be covered in all hospice trainings. How those topics are covered and what additional topics are presented are up to the individual hospice. Trainings usually run 18-20 hours, but I find that’s barely enough time to cover what we are supposed to cover and still go deeper into more experiential work like guided imagery, role play and group exercises. I try to offer more extended time with the volunteers throughout the year on topics like “Life Review” and “Reminiscence and Legacy.” The training I offer has its roots in the original hospice training as it was given in this county back in the early ‘90s. I am still friends with many of the folks who set that up. Of course I have altered it as the years have gone by and I have added to my own experience. That original hospice spirit is (I hope!) still intact. In any case, I believe it’s a better, more meaningful way to train than individually on a computer.

Carla: What qualities do you look for in hospice volunteers?

Steven: Flexibility and openness are absolutely essential. A comfort with ‘mystery’ and being okay with ‘not knowing’ is crucial to the longevity of doing this work, particularly with volunteers.

Carla: People who choose to work within this field are often motivated by the depths of their own personal experience. Have you encountered times when the intersection between a volunteer’s personal wounds conflicts with their ability to care for others?

Steven: It’s common and natural for hospice caregivers to have their own grief to take care of, but I’ve found that sometimes professionalism masks pain in really difficult ways to get at. A young psychology student participated in my very first training in 1997. A professor in communications came in to speak. He did a role play with her about communication. She fell apart and left. She had learned to work with others, but had never learned to work with herself. During another training, there was a woman who was a psychiatrist — extremely smart and very intimidating to me intellectually. She kept at me throughout the entirety of the training trying to make me go ‘deeper’ with the trainees. During the final interview, she broke down in tears, overwhelmed by the feeling of powerlessness in face of working with the dying.

Steven Willey

(Credit: Carla Friedman)

Carla: I completed my first hospice training long before the mainstream medical and insurance communities were fully educated and accepting of hospice care as a common practice. Now almost fully integrated into our healthcare system, do you feel that the corporatization of hospice has diminished or enhanced its essential quality?

Steven: I feel that the soul of hospice is still the same, but I’m saddened by the pervasive necessity of ‘quantification.’ We seem, as a culture, to want to qualify everything, to measure everything to make sure we get our money’s worth. People don’t want to be cheated and are focused on getting what they feel they are ‘owed.’ That seems to have increased over the past seven years or so. San Diego Hospice had a fantastic and highly respected program. They were forced to close after a Medicare audit found that there were patients who were on service that may not have met hospice criteria. Proper documentation of a patient’s decline was also an issue.

Of course these are important issues, but the tens of millions of dollars San Diego Hospice will probably have to pay back sent a chill throughout the industry. More and more patients don’t fit into clear “six months or less” timelines, and the fear of more intense scrutiny has to be balanced by the care we want to give patients who still need hospice support. Oversight is good, but it shouldn’t be the center of the experience. The soul should be the center. The soul of this work is, though, completely intact, and I think it always will be. Almost everyone I work with has that soul.

Carla: Do you find that those seeking hospice care for themselves or a loved one varies in terms of gender, race, economic strata and/or demographic?

Steven: It might vary culturally, but not racially or economically. The degree to which people allow themselves to be ‘vulnerable’ is the degree to which they accept or reject hospice.

Carla: As if working with the dying isn’t challenging enough, you have also both trained as hospice carers and counseled dying prisoners here in San Luis Obispo. What’s that like?

Steven: This work has taught me that the ordinary things are all that matter. It doesn’t matter to me what someone has or hasn’t done in their lives — political, religious, moral, etc. What matters is what their soul is doing in that moment: what are they looking at, what’s hard for them, what do they hear, the immediacy of the present. Volunteering in the prison has given me so many insights into things like forgiveness, hope and genuineness, and my education there is ongoing. I will always be deeply grateful to the men I’ve worked with in the prison for what I have learned from them. I hope we are all able to look at our lives and see at least one or two things we’ve done that really matter.

Carla: Being present without judgement, without agenda with a present mind and open heart?

Steven: Yes. I would add only the importance of being genuine. Of just being yourself.

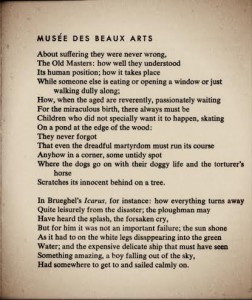

Carla: I know that you have a love of poetry, which you often share throughout the hospice trainings and volunteer meetings. Would you share one of your favorites with SevenPonds?

Steven: Sure. Here is one:

Musée des Beaux Arts (1940)

W.H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just

walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy

life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Carla: Thank you for speaking with us!

Steven: Thank you.

Who Guides Hospice Volunteers? An Interview with Steven Willey, Hospice Volunteer Manager

Who Guides Hospice Volunteers? An Interview with Steven Willey, Hospice Volunteer Manager

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?