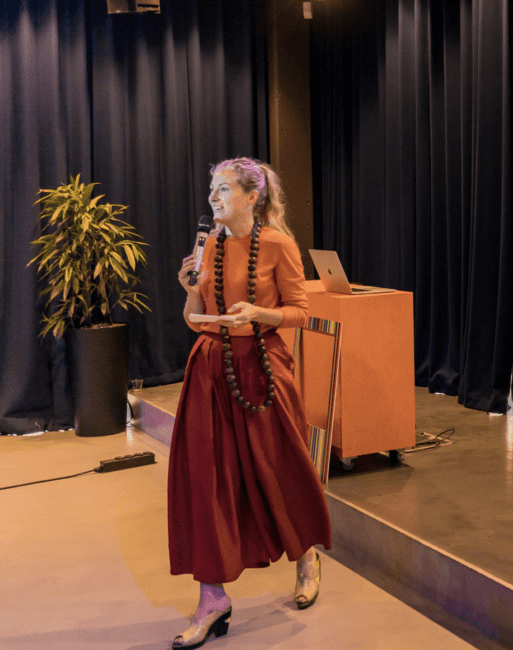

Susanne Duijvestein

In 2017, after 11 years of working in the financial sector, Susanne Duijvestein decided to follow a new path. Susanne is now a funeral director, who specializes in sustainable, non-traditional funerals. Since starting her company, Bij Afscheid, she has helped families all over the Netherlands say goodbye to their loved ones with graceful dignity. Located in Amsterdam, her work offers those who grieve alternatives to traditional funerals by working from a business model that emphasizes healing over profits.

SevenPonds had the privilege to sit down with Susanne, to discuss her company’s mission and vision for the future of funeral direction in the Netherlands.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Susanne Duijvestein at Museum Night 2019, at Mediamatic

Photo Credit: Anisa Xhomaqi

What drew you to sustainable funeral direction? Why did you choose this profession?

I felt a calling to show people other ways they could develop a relationship, an intimate relationship, with death. I also wanted to offer alternatives so that family and friends could deal with death more naturally in both the physical and emotional aspects of their lives. I had assumptions about how the funeral industry works and its commercial, capitalistic attributes. In the Western world, we buy a funeral. We are presented with a catalog of all the options the director has. What we often don’t know is there is a whole alternative world beside it. That felt like my calling–to show other ways, more healing ways for us to deal with death. When we lose someone we love, we can create ways to have a healthy relationship with death. I wanted to be a part of that.

I love the way you described these alternatives, as a world operating beside what everyone thinks of funeral options. It speaks to the fact that there are other options, but not many know about them.

Yes, we need more critical awareness and consciousness when it comes to saying goodbye to our loved ones. It has everything to do with the taboo of death as a whole. What I notice in my practice is that people avoid pain. Our brain is programmed to avoid pain. When we lose someone, it is painful–it seems very welcome to have this entrepreneur who shows you some options. But it’s interesting to notice it has the same feel as the wedding industry. When planning a funeral, people may feel, “We need this and we need that.” We buy stuff in order to avoid the pain. It’s addictive behavior. We buy stuff just to not be with our pain. That’s what the funeral industry is counting on–people buying stuff because they’re in pain. That’s something I’m very worried about.

I want to show these alternatives because there are way more beautiful options that may not cost much money. I want to protect families who may not have a lot of money from this industry. Often, families spend 8-10,000 Euros on a funeral. It is very simple to reduce this to 1-2,000 Euros by creating much of the ceremony and materials ourselves, which can also be part of the healing process. Funerals that cost less money usually have a lot more love and creativity. We produce a more beautiful and healing experience.

Before we dig into the work you’re doing in Amsterdam, do you have a personal experience with death or a funeral that still impacts your relationship with death today?

I always want to open up about death and my relationship with death. I did lose a few friends of mine when I was around the age of 20. I noticed the force of the industry makes almost every funeral very standard, not personal. Though they pretend to organize personal funerals, there is a tendency to standardize the experience in an effort to be more efficient and profitable. All of the funerals seemed the same.

When my friends died at a young age, I was touched by the ownership the friends took over the funeral. There was this standard, commercialized experience, but the friends really wanted to own the funeral, to create rituals, to choose something very personal. For example, when I was 20, a friend died who was only 22. At that age, he was a DJ and his life was about being with friends and cars. All his friends collected their money to make sure a Ferrari was there at his funeral. That was the front car of the whole procession. Here was this example of best friends who decided to rent this special car and make sure they honored their friend. I think everyone at that funeral has that image of the Ferrari at the beginning of the funeral procession in their memory. I was touched by this act of friendship.

Thank you for sharing that story. I just want to mention, you smiled the entire time you told it. Though it was a tragedy for such a young man to die, there is obvious joy in your memory concerning the friends banding together to make sure they honored their loved one by having this super- cool car at the funeral.

With your work, do you operate similar to a traditional funeral home, or are you offering help as families may choose to DIY funeral items such as a death shroud or handmade coffin?

My work starts when someone has died. The first part of my work is the ritual washing of the body. In the Netherlands, this is not always a family ritual, but sometimes it is. The undertakers may do this themselves, but often, I try to persuade family members to join me in washing and dressing the body. It’s common here to keep someone who has died at home. If someone dies at home, we often keep them at home. We have these cooling apparatuses that keep the body preserved in a bed at home until we are ready to lay it to rest. I love this tradition because it enables the family members to have an unlimited amount of time to be with someone, instead of the body being taken to a funeral home, where you’d have to make an appointment to see them.

There are tasks we must do in grief work. One of the steps is to confront the reality of our loved one’s death. Keeping the body at home allows people the opportunity to realize their loved one has truly died and is no longer living. It helps us to comprehend they are gone.

What sets your practices apart from traditional funeral homes?

I don’t have a business model that is founded upon the more I sell you, the more money I make. I don’t care if you buy the most expensive coffin, or you make one yourself. My business model is based on an hourly rate, not what they purchase. If a family only needs four hours of my time to help them set everything up that they want for the ceremony, that’s fine. I get paid those four hours. If a family needs forty hours, that’s also fine. I don’t care what the families purchase. I am here to help them heal.

I encourage people to use their talents. I try to empower people. People who have just lost someone don’t feel empowered, so I try to make people feel in control. Being vulnerable can be powerful, so engaging with the pain and grief is important. I try to make them feel they have power and ownership over the ceremony. I guide them by just being there with them as a human being who happens to know the options available to them as they prepare to lay their loved one to rest. I am constantly asking, “What do you need? If you check in with your feelings, what do you actually need?” The answer will never be an expensive coffin. We need a safe space, we need to create something, we need to come up with this crazy idea of the Ferrari at the funeral.

Susanne demonstrates how to wrap a death shroud at Mediamatic

Photo Credit: Filippo Giuseppe Iannone

This leads me to what you’ve become known for — creating death shrouds. Is this something you came to after you started this work, or something you’ve been interested in for a while?

Growing up, my mother always had these patchwork projects. I grew up with sewing, embroidery, and a love for fabrics. When I entered this field of work, the possibility of being covered in a shroud instead of a coffin was very appealing to me. I loved the idea of being shrouded versus being laid in a box.

The death shroud opened a world of possibilities for me. Knowing that it could be any color, any design allows for it to become an expression of a person’s identity. This happened naturally, and I began to research the history of death shrouds. Being covered in a shroud is an older practice than being placed in a box. In the Netherlands, we have a large Islamic community, and they have a saying, “In death, everyone is equal.” Jewish tradition has a similar thought. This idea seemed in total contrast to the wedding vibe of a standard funeral, where everything has to be Pinterest perfect.

I began organizing workshops, where people can design their own death shrouds so that we can normalize death and preparing for death. Creating an object, something you make with your own hands, becomes “you can keep it in your closet for the day you will need it.” I noticed, for many people, being shrouded when you die is a softer way to leave this world. People are inspired by the idea they can create it themselves.

Do you feel a lot of younger people today are open to talking more about death than previous generations?

I don’t collect data, but we once had an extra large version of the workshop during Museum Night, where all museums in Amsterdam are open. Every museum holds a special event. At Mediamatic, many people, including those who were aged 16-18, came to create miniature versions of a death shroud. Young people are interested in death and curious about it. At my traditional workshops, the participants are all ages, from 22 on.

I find many young people are ready to talk about death. I think it has to do with trauma and what we’ve all survived. I think my parents were a bit more open than my grandparents to talk about death. Today’s youth feel done with the business aspects of funerals and dig into the spiritual side of death.

A death shroud from Susanne’s workshop

Photo Credit: Filippo Giuseppe Iannone

Do you have any special memories from your work regarding death shrouds?

There are so many, but I will share two very meaningful stories.

Again, it was about a group of friends. A woman had died, and in preparation for her funeral, her best friends created a beautiful ritual together. They found out that their friend wanted to be shrouded, so they collected flowers from their friend’s garden. It was summer, and there were so many beautiful flowers. They used them for a technique called flower pounding. It’s usually done by hammering, but these women used rocks. They made a pattern of all these petals, almost creating a mandala. By pounding the petals with the rocks, they pushed the pigment into the shroud, which gave the fabric this beautiful dyed design. In the midst of hitting the flowers, the women took tea breaks and stayed engaged with each other throughout the creation. They took ownership–it was their way of giving their friend a Ferrari. I can still see the women on their knees on the ground.

Another story is of a women who had cancer and knew she didn’t have much time left. She read an article I’d written about the history of shrouds, and she was inspired to make her own. She’d been collecting pieces of silk because she loved the fabric so much. These pieces were all different colors and she kept them in a box. She began to patch them together to create her own shroud because she was still able to sit and sew. In her final two months, she worked on it; however, she wasn’t able to truly construct it fully before she died. What she made would’ve been a suitable under layer of the shroud. When she died, just before she was cremated, the woman’s son and daughter decided to keep the unfinished shroud.

What would you offer to someone who’s starting to think about death shrouds: what tips would you give?

- Make sure you only use natural fabrics (and natural thread).

- Make it an expression of your uniqueness. How can this be a portrait of you?

- Make it something that can be used during life. Perhaps you can use it as a table cloth or wall hanging so that what you are wrapped in at death you lived with during life.

Keep watch for our Practical Tip next month, where Susanne will tell us how to create our own death shrouds.

A Sustainable Funeral Director Offers “A Ferrari for Every Funeral”

A Sustainable Funeral Director Offers “A Ferrari for Every Funeral”

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”