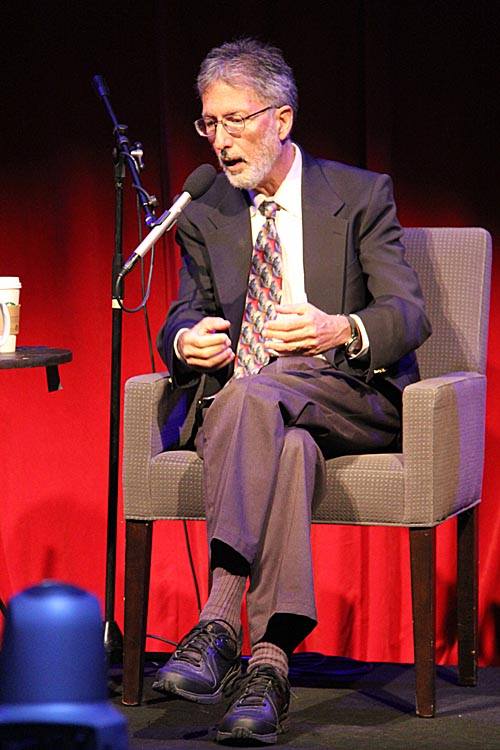

Dr. Charles Grob

Credit: researchgate.net

Today Sevenponds speaks with Dr. Charles Grob, Director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and one of the leading clinical researchers of psychedelic-assisted therapy. Dr. Grob discusses his experiences running a study using psilocybin to treat end-of-life existential anxiety in people facing impending death.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ellary Allis: How and when did you become interested in the therapeutic use of psychedelics?

Dr. Charles Grob: I discovered psychedelics along with everybody else in my generation in the 1960s. There were a lot of articles coming out at that time that I read while growing up. I had a few experiences with LSD in my freshman and sophomore years at Oberlin College in Ohio in 1968. But I realized at that time that a college dormitory was not the optimal setting for a response as powerful as the one that LSD elicits. Still, what came out of that was a lasting fascination with the topic.

I didn’t do another psychedelic again for 20 years, but I’d still look for material to read. Then in the early 1970s, I got a job as a research assistant for a dream research study. I had to stay up all night and monitor EEGs and wake people up periodically throughout the night while they slept in sensory isolation chambers to ask them about their dreams. And to stay up all night I needed things to read.

One of the doctors there had an incredible library in his office with all of the articles that had been written on psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted therapy through 1973. I just devoured that stuff! I found it so fascinating. Then one night I had an epiphany about what I wanted to do. I called my father and said, “Dad, I want to study psychedelics. There is so much they can teach us about the brain, the interface between the mind and the brain, about remarkable treatment models for mental illness.” He listened for a while and said, “Well, son, there may be something to what you say, but no one will listen to you unless you get your credentials.” So I went to medical school.

Of course, by the time I got out of medical school, all psychedelic research had been shut down, so there was nothing to do but read and hope that conditions would shift over time. In the late 1980s, I was recruited to UC Irvine, and I met a couple of other psychiatrists who shared my views on psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted therapy. Together, we started to write some review articles and protocol drafts, and it all got rolling.

Then in 1993, I came here to Harbor UCLA where I was recruited to be the director of child and adolescent psychiatry. I had a great chair named Dr. Miller who was very supportive of my interests in psychedelics. Dr. Miller understood that this was a potentially very valuable treatment that had, unfortunately, run into our cultural wall. As soon as I got here, I ran a few studies with MDMA (also known as Ecstasy) and one with ayahuasca in Brazil.

Ellary: When did you become interested in working specifically with people at the end of life?

Dr. Grob: Back when I was working at the dream lab and reading all of the psychedelic research, I had heard that a Czech psychiatrist named Stanislav Grof was in New York and about to give a talk. I went, and he presented some of his findings from the Spring Grove study in which they were treating people with terminal cancer. It was very moving. He got great results with psychedelic-assisted therapy, and I was fascinated.

Then in the late 1980s when I was at UC Irvine, I and a couple of colleagues wrote a critique of an article that had been published in the Archives of General Psychiatry, a very prestigious journal. It basically described so-called “serotonin neurotoxicity” in individuals who used MDMA. There were clearly some methodological flaws in the study and issues with how the data was being analyzed. My colleagues and I wrote a pretty long letter to the editor, and they printed it. Shortly after that, I got a call from Rick Doblin, the founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, who said that he wanted to come and meet me. He asked if I’d like to do a research study with MDMA, and I did. That was my first study.

Initially, our plan was to treat people with advanced cancer and anxiety. That was the protocol I sent into the FDA. But the FDA determined that we weren’t ready to treat a patient population because nobody had ever looked at MDMA in a normal volunteer population. It was a highly politicized issue. They told us if we came back with a protocol for a normal volunteer population for a Phase 1 MDMA study, they might look at that more favorably. So that’s what we did.

A few years later after I finished the normal volunteer study, I decided I wanted to submit another protocol looking at a terminal cancer population.

Dr. Grob speaks about his research

Credit: scpr.org

Ellary: You ultimately decided that psilocybin was a better option for terminal cancer patients than MDMA. How did you decide that?

Dr. Grob: By that time I was on the board of the Heffter Research Institute. We’ve been around since 1993, and our mission is to help develop and fund academic research with psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted therapy. I got to talking with Dave Nichols, who’s the president of Heffter. From those conversations, I began to think that psilocybin would be a better drug to use with this population than MDMA. Psilocybin gives you a more in-depth experience and touches more into the existential crisis that terminally ill people are wrestling with. Also, very importantly, psilocybin is physiologically much gentler than MDMA. MDMA can give you an easier time psychologically, but physiologically it can be pretty harsh—it’s part amphetamine. When we’re working with people at end of life, we need to be cognizant of the fact that their organ systems are shutting down. They’re starting to fail. So giving them a physiological stressor like MDMA could hasten their demise.

At the same time, psilocybin might be more psychologically challenging than MDMA, but it puts people more in touch with the existential reality of what’s going on and targets end-of-life existential anxiety. On MDMA, you might tell your partner or therapist very effusively how much you love them. But you’re not going to deal with the core issue as well as you do with psilocybin.

I think MDMA is a very valuable compound, but for select populations. It’s great for people with chronic PTSD, for example. Typically, those are people who are in good medical health, so the physiological challenges are not a problem. They can walk through and remember the traumatic event with the help of a therapist and develop mastery over it.

Ellary: Was there something that drew you in particular to people facing end-of-life existential anxiety? Do you have a particular interest in the topic?

Dr. Grob: Who doesn’t? It’s the universal condition we all face sooner or later. Initially, I was inspired by Stanislov Groff’s work, not only in the talk I went to but also a book he wrote with Joan Halifax and the paper publishing his findings.

When I got out of medical school I went into internal medicine. So I was dealing with people at the end of life. And in many respects, I was perturbed with how the medical profession was dealing with them—mainly just turning a deaf ear. Doctors are often uncomfortable even talking about death and end-of-life existential anxiety. It’s a difficult topic to grapple with in medicine, and I was struck by that.

Then I went into child psychiatry, so I was less involved with people facing the end of life. But it still seemed to be an area that was ripe for investigation. So I methodically collected articles on all sorts of issues and areas related to psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted therapy including everything that had been published on the topic of treating people at the end of life.

Dr. Charles Grob and Friends, Switzerland, 1990

Ellary: When did you initiate the study using psilocybin for terminal cancer patients?

Dr. Grob: It took years from the time I decided I wanted to do it to come up with a protocol that could get through all the regulatory processes: FDA, DEA, California Research Advisory Panel, my own in-hospital IRB, my own in-hospital research committee. Everybody had a critique, and I had to respond to all the critiques, so the protocol kept having to be changed. At the end of the day, I came out with a very good protocol, and we demonstrated feasibility and safety, and the icing on the cake was efficacy. We saw strong evidence that mood improved and anxiety diminished.

We ran the study from 2004 to 2008. We published our results online in 2010 and in print in 2011 in what was then called the Archives of General Psychiatry and is now called JAMA Psychiatry, the number one impact journal in the field of psychiatry. The peer-review process had evidently determined that this was an important area, which was nice to see because for decades psychedelic-assisted therapy had been ignored.

Ellary: Will you describe the environment you created during the psilocybin studies and the structure of the sessions?

Dr. Grob: At that time we had a research unit in the hospital that was funded by the National Institute of Health. I used the only single room on the unit because you really need privacy for something like this. It was your standard hospital room except that it had two heavy doors because it used to be the old sleep research room. That was good because it blocked out sound from the hall. Nevertheless, it wasn’t optimal for psychedelic-assisted therapy.

The day before each session, I and whoever my co-therapist was, (eventually it was Alicia Danforth, and before that, a nurse named Marycie Hagerty) would go in and put wall hangings up and place flowers around the room. We cocooned the person into a nice, pleasant space. There was a bathroom in the room so we didn’t have to take them out into the hall. They didn’t have to deal with anybody besides us.

This concludes Part One of our interview with Dr. Charles Grob. Please come back next week to learn more about his research and psychedelic-assisted therapy.

Can Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy Help Alleviate End-of-Life Anxiety?

Can Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy Help Alleviate End-of-Life Anxiety?

Having an Estate Plan Is Essential – So Is Discussing It With Your Children

Having an Estate Plan Is Essential – So Is Discussing It With Your Children

“Summons” by Aurora Levins Morales

“Summons” by Aurora Levins Morales