Dr. Charles Grob

Today Sevenponds concludes our conversation with Dr. Charles Grob, Director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and one of the leading clinical researchers of psychedelic-assisted therapy. Dr. Grob discusses his experiences running a study using psilocybin to treat end-of-life existential anxiety in people facing impending death.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ellary: During the session are you verbally processing with people what they’re experiencing?

Dr. Grob: Minimally. With psilocybin and people dealing with end of life, you don’t want to get in their way. We were approved for a moderate dose. Subsequently, the Johns Hopkins group and the NYU group, which basically replicated what we did, got permission for a higher dose, because we had already established safety. But with the moderate dose, I didn’t want our patients to get distracted with too much talk.

We treated everybody on Saturdays. We would admit the patient Friday afternoon to the research unit, and the medical residents who were assigned to that unit would work them up: They would draw some labs, do a history, do a physical. Marycie or Alicia and I would fix up the room and do some processing with the subjects, who we’d already met and spent some time with. We’d review with them again the parameters of the study. Also, very importantly, we’d review what their intentions were. That’s a very important question to ask anyone embarking on a psychedelic voyage. We’d ask them what their intentions were, what questions they had, what sort of healing they hoped to get out of the session. Then we would leave, and the subject would spend the night in the hospital.

What I realized after I ran the first few subjects was that I needed to bring in some sort of ritual. I felt that something was missing; it was a little too sterile. One of my best friends, who passed away a few months ago, was a man named Ralph Metzner. He was a great writer, very prolific, and he was one of the main researchers studying psychedelics at Harvard in the 1960s, along with Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert. I valued the way he had brought ritual into his studies, and I pulled the rituals I implemented from Ralph. I always asked my subjects if it would be OK to do a ritual because it wasn’t part of the original agreement. Everyone said yes, and everyone thought it was great.

What we did was call in the spirits of these plant psychedelics, because one way of looking at it is that the plants are endowed with healing elements. We would also call in the spirit of the four directions and the upper realms and the lower realms. That’s how we would start off. Then we would give them the medicine, and they would lie down, put the eyeshades on, and put headphones on with prearranged music we had chosen. Their instruction was to go as deeply as possible into the experience.

I and Marycie or Alicia would sit there for the entire six hours of the session, and every hour we would check in with the subjects, get their attention, get them to sit up and take off the headphones. We would ask how they were doing, take their blood pressure, and as long as everything was okay, they would go back into the experience.

If someone in the midst of it all, before the hour was up, felt they had something to communicate with us, all they had to do was sit up and say something. However, I didn’t encourage too much processing during the actual session. The point was to go as deeply as possible and to process with us afterward. At the six-hour point, the medicine would have worn off, and they would then process with us what had happened. And there were processing sessions during the following several weeks.

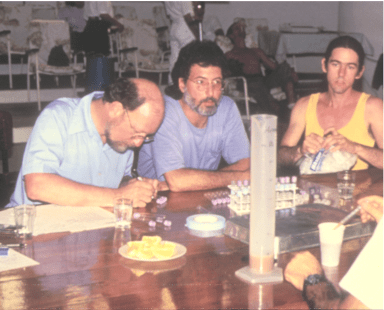

Dr. Charles Grob and colleague Dr. Alicia Danforth

Ellary: During the check-ins, did you ever encounter someone who wasn’t doing okay? Someone who really needed support?

Dr. Grob: My two most serious adverse effects were people that had received the placebo. We gave people an active placebo called niacin, which for most people just gives them a little tingle. But for some people, if they react and get the full niacin flush, it can be very uncomfortable. I had two people who for about 30 or 40 minutes were consumed with itchiness and were very uncomfortable. But everyone tolerated the psilocybin very well.

Ellary: So nobody went into a sort of dark, existential hole about their anxiety?

Dr. Grob: No. We gave people a moderate dose. That’s more of a risk with the higher, knock-your-socks-off dose they were giving at NYU and Johns Hopkins. But at the moderate dose, nobody had a problem. People had a lot of emotions — we had people who did a lot of crying, for example. In this study, everybody functioned as their own control. What was randomized was the order — whether they got the psilocybin or the niacin first. But everybody got one of each.

One woman came in for the second session, and I was pretty certain she’d gotten the placebo first. I was blinded as well, so I wasn’t sure, but for most people, the psilocybin usually starts to come on within about 45 minutes to an hour. Nothing was happening for this woman after an hour, two hours, and I started to get a little concerned: Could the research pharmacist have made a mistake and given us two placebos? By the fourth hour, still, nothing was happening. At that point, we decided to switch up the music. We had been playing something pretty bland, so we tried something more dissonant. One of my psychiatric residents went and got a Dead Can Dance CD, and started playing it for her. Within minutes, the floodgates opened and she was sobbing and sobbing for the next couple of hours. I was just sitting there trying to imagine what she was thinking and came to the conclusion that she was obviously crying because she was getting in touch with her limited mortality.

At the end of the session, I asked what had been going through her mind, and she said she had this vision that she was with her father, who had died many years previously. She was crying because while he was alive, they could never tell each other they loved one another, though they did love each other very much. She was crying for the lost opportunity to explicitly tell her father she loved him, and to hear from him that he loved her. Processing that was really helpful for her.

Dr. Grob in Brazil conducting an Ayahuasca study

Ellary: Will you explain the neuroscience behind why psilocybin seems capable of relieving anxiety?

Dr. Grob: Well, you know, nobody really knows for sure. We know it’s primarily working on the serotonergic system, specifically the serotonin sub-receptor known as 5-HT2A. It’s stimulating that receptor as well as about 10 others, and we’re learning about new receptors all the time, so it’s an evolving understanding. That aspect of the serotonergic system seems to be playing a role. That’s also one of the targets for many of our psychiatric drugs, only psychiatric drugs don’t trip people out like this, of course.

An English researcher named Robin Carhart-Harris has done a lot of brain imaging studies, and he’s come up with this hypothesis that a neural network in the brain known as the default mode mechanism goes offline, or is shut down, with a classical psychedelic like psilocybin or LSD. It basically causes a rebooting function, like when you turn your computer off and then on and it reboots. Turning the default mechanism off and then allowing it to reboot, Carhart-Harris believes, has something to do with the range of effects psychedelics will induce.

Ellary: Are there any studies you’re involved in currently around psychedelics?

Dr. Grob: I’m working now with Ira Byock, who is one of the leading people in the country in the world of palliative medicine. I’m also working with Tony Bossis, who is a psychologist who has done a lot of work in psycho-oncology. The three of us have developed a protocol to implement in the palliative care setting. The protocol would involve training palliative care doctors and nurses to be facilitators for people further towards the end of their lives than studies to date have focused on. We just found out we got a big grant, and now we just have to beef up the protocol, send it to the FDA, and come up with our final list. We’ve got many more places and people interested in being a treatment site than we have room for, so we’ll see.

Ellary: Can you describe some of the lessons people report having learned from their sessions?

Dr. Grob: This is existential medicine. It really gets you in touch with your deepest, deepest level. When people are dying, they are often in an existential crisis. Part of that is losing the thread of your life, losing the sense of who you are. The sense of purpose you had no longer seems to be there. I’ve observed that people, with the aid of psychedelics, can reconnect to who they are, to who they’ve always been. That thread suddenly reattaches, and there’s meaning and purpose — maybe not what you thought it was previously, but there’s still meaning.

The sense of priority shifts around, so connecting with your loved ones and putting words to that love and explicitly stating it is something that often happens. What we saw in the wake of these treatments was a lot of healing within family systems and among friends. So I think it helps people exit with a lot less unfinished business than if they had not that opportunity.

Ellary: Thank you, Dr. Grob, so, so much. I really appreciate you taking the time to speak with SevenPonds about all of this. Your work is so groundbreaking.

Dr. Grob: It was my pleasure!

Did you miss Part One of our interview with Dr. Grob? If so, please check back here.

How Can Psilocybin Help Hospice Patients Facing End-of-Life?

How Can Psilocybin Help Hospice Patients Facing End-of-Life?

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap