Today SevenPonds concludes our interview with Frank Ostaseski, an internationally respected Buddhist teacher, cofounder of the Zen Hospice Project, and founder of the Metta Institute. Frank has lectured at Harvard Medical School, the Mayo Clinic, and Wisdom.2.0, and teaches at major spiritual centers around the globe. He is also the 2018 recipient of the prestigious Humanities Award from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

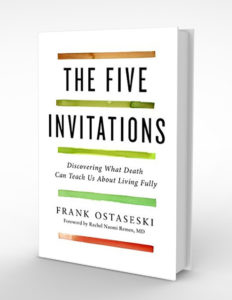

Frank Ostaseski’s groundbreaking work has been featured on the Bill Moyers PBS series “On Our Own Terms,” highlighted on “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” and honored by H.H. the Dalai Lama. He is the author of “The Five Invitations: Discovering What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully.”

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and readability.

Kathleen Clohessy: In your book, you discuss the need to confront our suffering in order to access the innate qualities that allow us to heal. But that’s such a difficult thing to do. Where/how does a person — someone who doesn’t have a foundation in contemplative practice or even spiritual practice — start?

Kathleen Clohessy: In your book, you discuss the need to confront our suffering in order to access the innate qualities that allow us to heal. But that’s such a difficult thing to do. Where/how does a person — someone who doesn’t have a foundation in contemplative practice or even spiritual practice — start?

Frank Ostaseski: In Western culture, we are taught that if suffering exists, something is wrong. It is a mistake. It has no value.

As a result, we have become masters of distraction. Our primary human practice is to protect ourselves from discomfort. Each day consumed with distraction; surfing the Internet, watching TV, working long hours, drinking, eating. Our approach naturally leads to epidemics of alcoholism and drug abuse; compulsive overeating, gambling, and shopping; and an insecure attachment to our technological devices.

Suffering is exacerbated by avoidance.

The willingness to see and accept what is true is the first step in working with suffering. The great African-American writer James Baldwin once said, “Not everything that can be faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed that is not faced.”

Suffering occurs as a chain reaction: stimulus-thought-reaction. We may not have any control over the stimulus that causes us pain. But we can shift our relationship to the thoughts about and emotional reactions to the pain, which frequently intensify our suffering.

After my heart attack and a triple bypass surgery a few years ago, a famous Tibetan Buddhist teacher kindly called to wish me well. I knew he had heart problems himself, so I asked him how he dealt with it all — the drama, the confusion, the depression and the beauty. I expected him to offer me some esoteric meditation practice.

Instead there was a pause, after which he said, “Well, I thought to myself, it’s good to have a heart. And if we have one, then we should expect it will have problems!” The teacher giggled in his very Tibetan way, reminded me to get plenty of rest, and hung up the phone.

I realized he was right. It was true. All humans have problems. All beings feel pain. Once I was able to accept that I had a fragile human heart I could relax around this temporarily painful situation. In so doing, my suffering also relaxed.

We don’t need to meditate to learn to work with suffering, (although that could help). We just have to be willing to look, to become familiar with that which we are trying to avoid.

When you are afraid, don’t you know that you’re afraid? Sure, there are signs and symptoms; maybe your mouth gets dry, your chest tightens, your mind starts strategizing. Becoming familiar these signals helps us to identify fear as it’s arising and provides the opportunity to intervene with fear before it becomes panic.

If you know you are afraid, the part of you that knows, that is aware of the fear, is not afraid. Then we have a choice, to function from the fear, or to function from the knowing.

Kathleen: I particularly enjoyed the section of your book “Bring your whole self to the experience,” where you discuss the “inner critic” and how it shapes so much of our lives. Can you talk about it a bit? Where does this critical voice come from? More importantly, how can we stop it from dictating how we live our lives?

Frank: The critic is the enforcer, demanding compliance to an acquired set of standards and moral codes. It’s the voice that says, “My way or the highway.” Often in our most vulnerable moments, when we would benefit from tenderness, we club ourselves with self-judgment.

The inner critic knows your every move, every trick up your sleeve, every bit of your past. You shower with it. Take it to work. It sits next to you at every meal and even sticks around for dessert. It’s there during and after sex. And yes, it’s also there when you are dying.

The pursuit of perfection is learned early on and, for most of us, becomes a lifelong addiction. This is why, in order to bring our whole self to the experience, we must address the often unconscious, corrosive voice of the inner critic.

When all of us were children, our well-intentioned parents and other authorities did their best to show us right from wrong and protect us from harm. We needed guidance to grow into a healthy adulthood and navigate our way through society’s codes of conduct. Gradually we internalized that judging voice.

The critic is the protector of ego. It denies everything else. It doesn’t know your soul. It doesn’t trust your heart. It doesn’t have faith that your intuitive gut sense. It doesn’t trust in your ability to reason and evaluate as a way to navigate through life’s dilemmas. We must be willing to act on our own behalf.

There is an alternative to the critic. It’s found in the movement from judgment to discernment. Judgment is a harsh and aggressive habit. It shuts down the conversation, binds us to the past and old behaviors. Discernment makes space, helps us to have perspective, and allows more of our humanity to show up. Then wisdom can emerge and we can choose a more beneficial future.

The critic may have served a purpose back in kindergarten, but it’s time to trade in our old model.

Kathleen: You also spend some time in your book discussing our addiction to “busy-ness,” and the importance of finding a place to “rest in the middle of things.” Assuming that many of our readers are not skilled in mindfulness or meditation, what tips could you give them for learning to find an oasis of calm in their lives?

Kathleen: You also spend some time in your book discussing our addiction to “busy-ness,” and the importance of finding a place to “rest in the middle of things.” Assuming that many of our readers are not skilled in mindfulness or meditation, what tips could you give them for learning to find an oasis of calm in their lives?

Frank: I love to lie in bed on a cold winter morning. The sheets are soft and warm. My body is well rested and enjoys taking refuge under the blankets. My mind is at peace and has yet to leap forward into the day’s tasks. For a while, all is right with the world. A moment of perfection.

Then I have to pee.

After a moment of resistance, I run quickly to the bathroom. Upon attaining the temporary ease of release, I leap back under the blankets in the hope of re-creating perfection. But I can’t get everything back the way it was just moments earlier. I can’t create conditions that are capable of providing an enduring happiness that is resistant to change.

The gift of impermanence is that it places us squarely in the here and now. It relaxes the tendency to manipulate the conditions to achieve happiness. We learn to let go into uncertainty, to trust that our basic nature and that of the world are not different. Then the fact that things are not solid and fixed becomes a liberating opportunity, rather than a threat.

Reflecting on this might cause us to savor the moment, to imbue our lives with more appreciation and gratitude.

Kathleen: You also talk about different types of courage, one of which is the courage to be vulnerable. In our society most people look at vulnerability as weakness, but you say that’s not true. How so?

Frank: Vulnerability is not weakness; it is non-defensiveness. The absence of defense allows us to be wide open to our experience. Less defended, we are less opaque and more transparent. We become sensitive to the ten thousand sorrows and the ten thousand joys of this life. If we are not willing to be vulnerable to pain, loss, and sadness, we’ll become insensitive to compassion, joy, love, and basic goodness.

The courage to love requires vulnerability. Is there a more vulnerable state than love? It is full of risk, uncertainty, intensity, intimacy, conflict and truth-telling. Being vulnerable means we are sensitive, impressionable, more receptive to others and to our own inner guidance. We recognize the illusion of control, the reality that suffering is inevitable, and we are invited to release our grips and let go into the inexplicable and unpredictable.

Kathleen: We live in such a divided, polarized society today, it seems that everyone is so firmly entrenched in their positions that we can’t see anything but our own point of view. Do you have any suggestions as to how we as individuals can begin to change that?

Frank: To be human is much more than being born, getting an education, finding the right partner, or buying a pretty house on a nice street, just so that you can sleep, wake, work, go to bed, and do it all over again.

It’s an invitation to feel everything, to come into direct contact with the strange, beautiful, horrible, and perfectly ordinary thing we call life. It is an opportunity to be conscious of the fact that some of us will make love while others make war. To recognize the truth that there are babies like my granddaughter born into loving arms and caressed by a mother who kisses her bright future into her child’s cheeks, and there are babies like Carolyn, a woman I knew whose parents left her in a dumpster as a baby.

To be willing to see that there are teenagers being shot in our schools and others that are speaking truth to power. To embrace the night screams in Syrian refugee camps and the giggling of children in living rooms under tents made of couch pillows and bed sheets.

There is devastation and hopelessness, and there is passion and holy commitment to creating a better future for everyone.

Kathleen: Lastly, of the five invitations, is there one that you believe most important? If I could incorporate just one of them into my life, which would you suggest it be?

Frank: I think that is a good question for your readers. Pick one and start. As John Muir once said, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

Kathleen: Thank you, Frank, for sharing your insights with me and our readers at SevenPonds. It’s been a pleasure!

Did you miss part one of our interview with Frank Ostaseski? If so, please catch up here.

How Can Confronting Our Suffering Enrich Our Lives?

How Can Confronting Our Suffering Enrich Our Lives?

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition