Chris Wilson, RN, lawyer, bioethicist, and advocate for bringing ethics into care facilities

Chris Wilson wears many hats: RN, lawyer, bioethicist, and founder of Community Healthcare Ethics. The certified healthcare ethicist is passionate about bringing conversations around informed consent, advance directives, and ethical decision making outside of hospital settings and into care facilities. Chris linked up with three other medical providers to start Community Healthcare Ethics, an organization aimed at expanding bioethics into care facilities, both through trainings for staff and direct conversations with families. Based in California, Chris sat down with SevenPonds to share more about her work.

Could you share what your career path was like?

After high school graduation I did some work at a nursing facility and I learned what an LVN was. I said, “Oh no, I can’t become a nurse, oh no, it’s yucky!” A nurse who was there and who later became my mentor said, “You can acclimate yourself to it if you really want it. Why don’t you help me do patient rounds and you will see some stuff you think you can’t handle but you can.” So I became an RN.

I worked in both hospitals and long-term care facilities. I loved long-term care; I love that population. Eventually, I became the director of nursing at a long-term care facility. But it eventually came back to me that I really wanted to be a lawyer. So I was a nurse during the day and went to law school at night. And, of course, understandably, I ended up as a lawyer in healthcare law, primarily as someone who defended healthcare providers because I know the job; I know what it’s like. And I know when things are not okay, when something went wrong, and the case gets settled.

But there was this other little thing I picked up on. When the family was in a dispute over issues with the care being provided, I would be called in as the nurse to come to the room, try to calm things down, listen, and help them make a decision. I heard the term bioethics, and I learned about the field of bioethics and ended up going back several years later and getting a masters degree in Healthcare Ethics. Now I do official ethics consultant work, like ethics committees at the hospital. But it also has given me a lot of insight into how to be that nurse again, who can help people with difficult stuff. So I do that, too. Sometimes I help individuals; sometimes I do a mass presentations for nursing facilities or healthcare providers; and sometimes I do consulting for lawyers, who need someone to give what is in essence an ethics opinion that they might need to use in a court proceeding.

Tell me more about ethical consultation in care facilities.

There are a lot of certified clinical ethicists out there. Sadly, they are rarely in long-term care facilities, the population that I care about. Normally they are in hospitals. The reason I went back to get my degree in bioethics was that I wanted to bring it back to that clientele. But who’s going to pay for it? I do a certain number of things pro bono.

So is it an issue of funding?

It is very much an issue of funding and regulations that don’t really address that. Long-term care is regulated by the federal government but also the state government. And the facilities’ focus is making sure they’re complying with regulations. And that’s not a bad thing.

How do you get referred to cases in long-term care facilities?

It comes from wherever it comes. I don’t really have any kind of a marketing presence, so it’s word-of-mouth. The thing I like the best is when somebody invites me into their situation and says, “We’re having a problem. I don’t know what’s going on here, and can you just come and see what’s going on.”

How did Community Healthcare Ethics start?

That came out of my initial desire to bring this whole concept of healthcare decision making, and how it should be done, to every single nursing home. I wanted to be involved more with helping people get through these difficult times, so that they can have an understanding of what’s going on, and so that decision-making can be discussed, and the right questions can be asked about what the relative would have wanted. Hospital ethicists do this well. If someone is in the hospital and there’s a clinical ethicist, they’re going to get into this type of conversation. But what about someone who’s not in the hospital?

What are some of the ethical questions that get raised in care facilities?

I did a presentation once for an assisted living community, and I talked to them about their advance healthcare directives. I asked the room, “Does the person you named in your healthcare directives know that they’re the person that’s going to be called if you need somebody?” And the room was blank. No one had talked about it further with anyone.

And it really does require that nuanced conversation ahead of time. I love being a part of that, and I’m happy to listen to families when they’re having disagreements about what Dad would have wanted. In those conversations, I talk about the basic principles of bioethics, such as autonomy. “Your dad can’t tell you what he wants, but we get to sit in his shoes and think about what he would have wanted, and talk about the risks and benefits.”

So often what happens is the doctor’s office will just give somebody a POLST form and ask them to fill it out. But it requires a deeper conversation with a health care professional to understand what is being discussed. And then sometimes if a family member is making decisions for their loved one, they may make decisions based on anecdotal stories rather than the real situation of their loved one. For instance, questions come up about artificial feeding and nutrition. One decision-maker said, “Well, I would never want to stop feeding my mom under any circumstances, because that happened with my friend John’s mother and they starved her to death.” And we talked about it, and I presented some of the literature, and said, “Look, I don’t know if things were done right with your friend John or not. I can’t tell you that. But here’s some information about when artificial feeding can cause more harm than good.” Because you can’t base your decision off somebody else’s experience.

What are the biggest challenges you face in this work?

My work in care facilities is really more about teaching those who work there how to handle these situations. I make myself available to family members in the moment who want my help. But mostly what I’m doing in care facilities is educating, whether it’s about a new law in California about informed consent, or if it’s about unrepresented individuals who lack decision-making capacity.

When I am working with families, though, the biggest challenge is a misunderstanding of healthcare and how things work. Our healthcare system has become very complicated, and the treatments we are able to give have improved. But the public watches TV and sees a hospital show about someone who gets CPR because they collapsed on the golf course and recovers completely. And that’s not always the reality of how things go for people. So the expectations versus reality piece can be challenging. Also, the misunderstanding of things like hospice, like believing that it will make someone die at the end of six months, when actually it could be a really great help for the family right now.

And then sometimes in end-of-life care what comes up is siblings arguing and accusing the other of wanting one type of care just to inherit the parent’s money. Some families don’t get along and don’t trust each other. Sometimes they don’t trust the nursing home; some families get very upset about their relative’s condition and blame it on the facility no matter what. They may be expecting something that is unrealistic. It is stressful having a loved one ill and feeling like there’s not enough being done. And they’re entitled to their feelings. But having a bioethics consultation can help clear things up. Problems have occurred in nursing homes that have been legitimate, not just a family member who doesn’t understand. But in many cases, I can talk with the family and help them understand what’s going on.

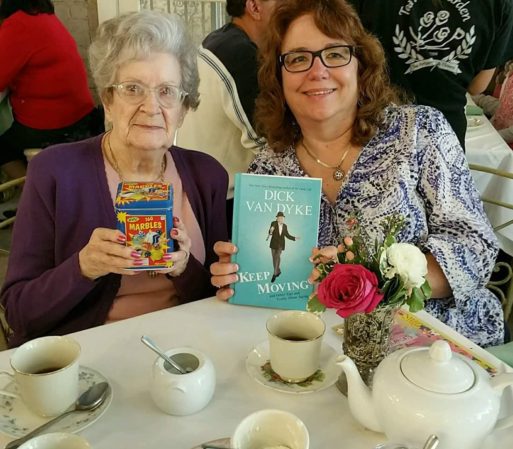

Chris and her mother — with all her marbles intact!

I hear so much in your work, a desire to broaden perspectives and just add nuance to understanding care.

Each situation is unique, and it’s about understanding that. And people aren’t just defined by their condition or their age. You can’t write people off after a certain age. When my mother was 100, I took her out to tea and I gave her a can of marbles. I told her, “The reason you have that can of marbles is when people talk over your head or think you can’t understand anything just because you’re 100, you can say, “Look, I’ve got all my marbles, want to see them??” She just cracked up. And she kept that box of marbles on the shelf next to her as she was being cared for, mostly just to give herself a laugh. She had a sense of humor and mental clarity her whole life, up until the very end.

Is there any advice you want to give our readers?

The biggest piece of advice is that healthcare directives and POLST forms need to be discussed — both with someone in the medical profession, someone you know like a nurse or a doctor, so you understand exactly what kind of care of want or don’t want, and then also with the person who is going to be making those decisions for you, your decision-maker. Talk to that person too. It’s the biggest part of the communication about your preferences.

“Improving Healthcare Decision Making: Bringing Bioethics into Care Facilities”

“Improving Healthcare Decision Making: Bringing Bioethics into Care Facilities”

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull