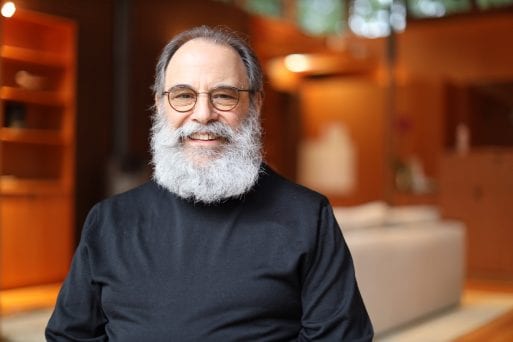

William Spear wears many hats. A self-described “lifelong student,” he’s studied death and dying with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, Buddhism with Tibetan Lama Sogyal Rinpoche and macrobiotic health with Japanese practitioner Michio Kushi. After recovering from an illness in the 1970s by changing his diet — based on advice from friends in Copenhagen, Denmark, where he was living at the time — Spear became passionate about macrobiotic principles. When he returned to the U.S., he began working with people who were very sick, including those diagnosed with later-stage cancers, to provide a macrobiotic approach to the end of life.

In the late 1970s, Spear was struck by a consultation in which his macrobiotics teacher advised a patient dying from metastatic colon cancer to seek medical help. “I thought to myself, I cannot read the writing on the wall like that to a patient,” Spear said. “I need to know how to help them pass. And I went home and I called Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.” Kübler-Ross, whose famous seminars at the University of Chicago Medical School formed the basis for her book, “On Death and Dying,” invited Spear to come take a workshop. Spear joined her in Maine, and continued to study with her over the years while consulting with patients who had terminal illnesses. In the late 1980s, he created “Gentle Passage,” part of his Connecticut-based nonprofit Fortunate Blessings Foundation, which offered five-day retreats to caregivers in the U.S. and Europe. These retreats later became known as “The Passage.”

In addition to end-of-life care, Spear has worked globally with people affected by trauma, natural disasters and other unexpected life challenges. He created one of the nation’s first suicide prevention hotlines, established a street clinic, worked in drug and alcohol rehabilitation and was a disaster specialist with the Red Cross. Today, he serves on the board of Madre, an international women’s rights organization. Spear also authored “Feng Shui Made Easy,” one of the leading books on feng shui for a western audience, and consults on large-scale town planning and city development projects. He’s been married for more than 40 years, and has three grown sons.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve done a lot of work with underserved communities and people who are struggling. What motivated you to take on that role, beginning with the suicide hotline in 1968?

Probably privilege. I grew up in an intellectual, middle-class family, and when I attended the University of Cincinnati, I was one of 25,000 to 30,000 students and something of an outlier. I took a course on the inner city from this teacher who later became my mentor, and he showed us slides of what was happening two miles away — I had no idea that such poverty existed in a privileged college town. He was an extraordinary activist. Once, when I went to talk to him in his office, he was actually speaking to Martin Luther King, Jr. on the phone.

So I asked him, “What am I going to do with my life?” He asked me if I’d read Karl Popper, Maimonides and Martin Buber. And I said, “No.” And he said, “Well, what are you doing in college then?” He basically convinced me that I wasn’t going to learn much in English literature or organic chemistry about the kind of life I wanted to live. So I didn’t stay in college very long. And then, after reading all of those great classic authors, I started to look at what was going on in the streets. In addition to this phenomenal mentor, it was the sense of obligation, a sense of interconnectedness, and some sense of equanimity, that put me on the street.

How did studying with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross influence your work with the dying?

I’d been teaching macrobiotics seminars and workshops for about seven years, and I’d developed quite a puffed-up ego. And so I got Elisabeth on the phone, and I made sure she knew right away that I was a teacher — I mean I must have said that 20 times. And she just laughed and said, “Yeah, fine, come take my workshop.” So I signed up for a workshop about a month later. I sure learned a lot about myself and my own unfinished business. I had to face my own demons, and to look at what it really means to show up clear-headed and empty at the bedside of someone who’s dying.

Not long after that, in the early 1980s, I started to work in the AIDS community in New York. There were two, three, four funerals a week. People were just wracked with grief. And so I decided to create some retreats for hospice workers, because there were a lot of very compassionate people who would come into the role of palliative care provider but would burn out very quickly. I discovered that, just like me, they had all kinds of unfinished business that they didn’t know how to process. So I started The Passage, and ran a five-day retreat workshop for many years. It began with hospice workers, but eventually patients came who were dying, and then patients came with their doctors and their therapists. We realized that everybody’s the same, everybody’s got the same heart beating and the same unfinished business.

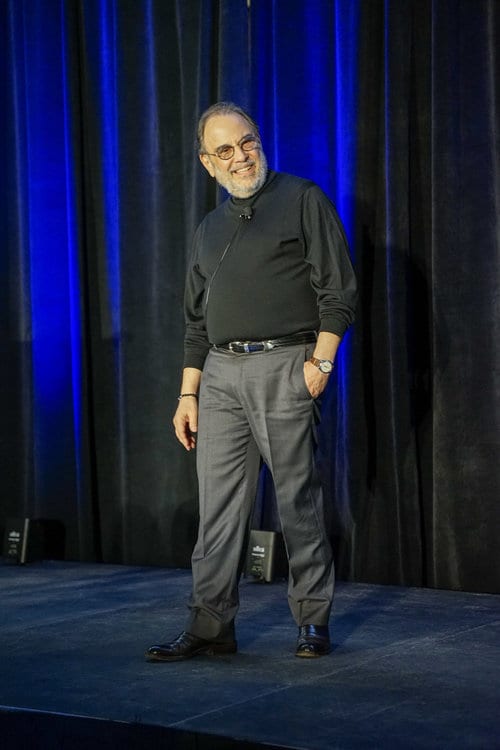

William Spear at the BrainMind Summit in November 2019

You’ve worked with a lot of varied groups at the end of life — hospice workers, caregivers, cancer patients, death row inmates. Have you witnessed any commonalities?

Death is the ultimate unknown, right? Whether you believe in heaven, or reincarnation, or that this is all there is, nobody knows for sure. So that’s a common thread for delivering care — we come blind to the bedside, without any real knowledge of what to expect. We just try to be there with a breath, with an open heart, unconditionally present. The people whom I’ve seen pass consciously, and in a way that I would consider a good death, are those who’ve had very few preconceptions. They’re present, they speak what they need to speak to family members or friends in the realm of unfinished business, and they operate not knowing what’s going to happen next.

I was going to ask you what makes a good death, so I’m glad you’ve addressed that.

It’s also important for others at the bedside to be present in their own experience. People often focus so much on the one who’s dying — they try so hard to stop that person’s suffering that they’ve repressed their own grief, their own suffering. In January, I joined a friend at the bedside of a 62-year-old man who died from a brain tumor. I was with that family for 10 days, staying in their home, as he died. That death was extraordinarily beautiful — his daughter was there, his wife was there, his brother was there, and there was a wonderful caregiver who was always beautifully present as a medical technician. I think that without question, everybody who was there had their experience, and not his. And to me, that’s a good death.

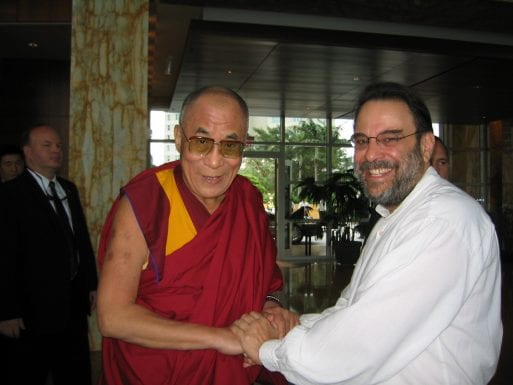

William Spear with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Florida

What are some common physical, emotional or spiritual needs of the dying that people around them can help with?

Those questions are addressed beautifully in “Five Wishes.” I think people should dive into them at any age, but particularly as they find themselves in a healthy situation in mid-life. Nobody gets off of this planet alive, so we might as well sit down and look through what we want at the end of life. I’ve been offering some courses on “Five Wishes” — how to fill it out, look at advance directives, and get a sense of how you’ll be with family and how you want family and friends to be with you at the end of life.

I’ve asked people a lot of times, in different situations: Is this a good day to die? And if it isn’t, why not? Because you didn’t write your book? Because you didn’t tell your sister you loved her? Because you didn’t bake bread today like you promised you’d do yesterday? Then get busy writing your book, write a letter to your sister, and go home and bake a loaf of bread. And tomorrow, ask yourself if it’s a good day to die.

What is it about “Five Wishes” that is so effective?

It’s a great courtesy. It’s a gift to your children, possibly to your care provider, maybe to your partner or spouse. But it’s also a process of acknowledging your own mortality, and helping you to wonder: what would you like to happen? Do you want to be cremated? How do you want to be touched? If I’m able to say that these are ways that I prefer to be touched — it’s a boundary issue that I might not be able to articulate at the end of my life. What kind of music do you want to hear when you’re lying there dying and can’t tell anybody to turn it off?

What are some of the more difficult end-of-life situations you’ve encountered, and how do you approach them?

Sometimes there’s a lot of unfinished business among the surviving family members. It doesn’t necessarily have to do with who’s in the will, but people commonly aren’t on the same page. Maybe the family has been out of touch, or the kids haven’t been very close, and suddenly they’re together in one of the most intimate experiences of their lives. There are a lot of elephants in the room at death that are not easily tamed and left outside. Nor must they be, because we’re human, and have our own personal lives and sufferings. It’s not like everything stops.

And then I think the other major challenge has to do with the specific modalities of medical care that are brought to bear. When I was studying with Elisabeth, I was very into macrobiotics, and when I started working in end-of-life care, I thought people could limit their suffering if they stopped eating so much animal food, and started to do some acupuncture, or some ginger compresses. And Elisabeth said to me: “People will die the same way they lived. If you’re eating roast beef and pork chops and taking aspirin for your headaches, and then when you start to die, you suddenly have someone feeding you brown rice and vegetables and doing ginger compresses, it just doesn’t work. It just doesn’t happen like that, so get over it.” What’s not uncommon is that people have different perceptions of what should be brought to bear, and how to relieve pain and suffering. Which is why I think that the Five Wishes are great. You can’t answer all of the questions, but at least you can cross some of them off.

William Spear with a soba master in Nagano, Japan

How did you become interested in feng shui?

I somehow discovered that a lot of feng shui originated with tombstone placement. They were much more interested in the gravesites than they were in dealing with the energies of the living. So I kind of immersed myself in feng shui studies, and started to offer some courses — as they say, those who know don’t teach and those who don’t know, teach. At first, there were six or eight people, then 30 to 50, and pretty soon there were 150 to 200 people in my workshops. This was in 1991, and I was teaching mostly in Europe, in London, though I did offer a few workshops on the East Coast.

And then an acquisitions editor from HarperCollins said, “You could write a book.” And I just laughed, and said, “That’s absurd.” She chased me for almost three years. I finally conceded and wrote the book, and it made really big waves. It sold out in 10 days, it’s in 16 languages, and recently it went into its 22nd printing. Suddenly the doors opened, and I became a feng shui consultant as well as a macrobiotics teacher with some end-of-life skills.

When you’re in end-of-life situations, does your understanding of feng shui ever come into play?

Absolutely, it’s extremely important. One of the big seminars I did in the mid-90s was called “Healing Design at the End of Life,” which looked at design in the public health space — ICUs and hospice facilities — that took the energies of the room into consideration. And I actually ended up consulting on the first brick-and-mortar hospice in the state of Maine, because one of the architects who attended that course approached me afterward and asked me to team with his firm. At the end of life, you try your best to give that environment some balance and harmony — not only for the person dying, but also for the family members and other people visiting.

If someone’s going to see a loved one who’s dying in the hospital, is there something simple they can do to make the space more harmonious?

If there’s a window with a long view, great. If not, then a picture with a very long landscape and a deep perspective is helpful, so that you’re looking out over the mountains, or the sea, or a large field. Rather than a poster with words, or a still life with a bowl of flowers. That way the person who’s dying has a long view of a journey. It’s also better than a portrait of family members, which is not the right thing in my opinion, because it’s hard to let go when your family’s right there in the picture.

Is there anything you’d like to add related to end-of-life care?

I went to visit Elisabeth Kübler-Ross about six weeks before she died. I’d seen her maybe four or five times since she’d fallen ill — she wasn’t that old, but she had a series of strokes that slowly eroded her health. At one point, I was alone with her, and Elisabeth said to me, “I flunked.” And I said, “What do you mean, you flunked?” She said, “I found out that there are two courses in life. There’s ‘Give Love,’ and ‘Receive Love.’ And I got an A in the first course. But I flunked the second course, and now my students and all of these people, they come and say, ‘Elisabeth, we love you!’ And I hate it.” So even this grand lady of death and dying, even this amazing, skillful sage of palliative care, couldn’t open her heart at the end of her life. Actually, she did in the last week or 10 days, because her son had a child, and only a few days before Elisabeth died, she was holding her granddaughter. But that was one of the most important things she ever said to me. I think that’s a lesson that many people in the caregiving profession could take away.

Thank you, William, for taking the time to share your insights.

Is Today a Good Day to Die?

Is Today a Good Day to Die?

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition