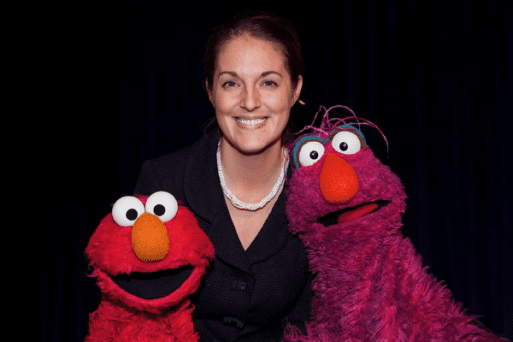

Evermore founder Joyal Mulheron poses with Elmo and Telly, who do their own work on Sesame Street to support bereaved families.

Joyal Mulheron has a long history in public policy. She’s advised the Obama White House and former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, and has worked with Republicans and Democrats, corporations and advocates. In recent years, she’s brought this diverse experience to bear in a new field: bereavement care.

Realizing that there was no other nonprofit looking at bereavement care as a public health issue, Mulheron was inspired to found Evermore in 2014. She was informed by the death of her own child, when she found herself shocked by the lack of understanding and practical support from her employer, caseworker, medical providers and other officials. Yet Mulheron is motivated less by her personal experience than by a widespread national failure to assist bereaved Americans, contributing to devastating long-term economic, social and health outcomes.

Evermore seeks to advance bereavement care by raising awareness, supporting community-building, and pushing for improved governmental and employment policies. Recently, the nonprofit succeeded in attaching a bereavement provision to the U.S. budget for the fiscal year 2021 that encourages several agencies at the Department of Health and Human Services to report on their bereavement-related efforts to Congress. In addition, Evermore is creating an employment policy to support bereaved family members and advocating for the establishment of a White House Office of Bereavement Care.

We caught up with Mulheron recently to hear more about Evermore’s efforts to advocate for bereavement leave and other policies to support individuals and families.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What motivates you to do this work?

I have talked to thousands of people from across the United States, and what motivates me is the chronic and persistent system failures that families are facing. There was no other nonprofit seeking to address the necessary systemic changes in order to help families and professionals facing some of the most difficult times of their lives.

Mulheron advocates for improved policies for bereaved individuals and families.

What was it about your personal experience that informed you, and that you see mirrored in the situations of others?

The way professionals responded; the way cost structures or the insurance companies responded; the way employers responded. I often say to people — particularly people who’ve lost a child — that it’s not only that you’ve lost your child, it’s all the other stuff that happens to you as a result. And whether I’m talking to someone who has served time for felonies or someone on Fifth Avenue, I get fist bumps to that statement. Those structural inequities are more pervasive in some populations than others, but they touch us all.

And what does that other stuff include?

It’s huge. Now first, it depends on whom you lose. Losing a child, losing a parent at a young age, or a sibling or a spouse — they’re all very different.

We have some related facts and figures on our website. Let’s take a child who’s lost a mother or father. It’s estimated that about 2 million children in the United States have lost a mother or a father. So we’ll take this one sentence that was recently written in a textbook for clinical psychology graduate schools: When compared to non-bereaved children, bereaved children experience “lower self-esteem, reduced resilience, lower grades and more school failures, heightened risk for depression, suicide attempts, suicide, premature death due to any cause, drug abuse, violent crime involvement, youth delinquency, and a greater number of, and more severe, psychiatric difficulties.” And that is just one population.

When you continue to look at the data and you find that Black children are three times as likely to lose a mother and twice as likely to lose a father by age 10 when compared to white children, and you look at these outcomes, they are stark and noticeable, and they change the life trajectory of an individual. So if you were to continue to just hover on that for a moment, you’ll find that nearly 90% of juvenile justice detainees report the death of a loved one prior to being incarcerated, with 65% of them experiencing multiple losses. So from a public policy standpoint, this isn’t just a personal tragedy. Incarceration, juvenile delinquency, drug abuse, suicide attempts, poor health, poor school outcomes: Those are outcomes of a bereavement event and the lack of a bereavement catchment system around the family and the aftermath.

How do you define bereavement for policy purposes?

The death of a loved one.

Joyal Mulheron speaking about the extreme

emotional difficulty of dealing with our current

system when her child

was terminally ill.

Credit: “We Can Do Better ” video

I was wondering if it might include things like caregiving for a terminally ill family member.

Certainly there are gray zones, but what we don’t want to mix here is the individual terminology and the population-level approach. These two things frequently get confused. Grief is a personal experience. Bereavement is the death event, whether that is someone who’s terminally ill — that is part in my mind of what the incoming bereavement experience will be. So it’s not just the aftermath and the example that you’ve provided, but I see bereavement as a population-level strategy. Many folks talk about counseling or hospice — those are direct services, not a population health strategy. Hospice, support groups, counseling, retreats, these are all wonderful tools, but we need to configure the employment systems. We need to configure our benefits systems. We need to configure the science. As a nation, we do not have the investment in innovative programs or policies being examined at the population level. For example, let’s just take cancer: Undoubtedly, you’ll find a group that talks about breast cancer among LGBTQIA+ Americans in some fashion. Finding those levels of nuance in bereavement is very difficult.

There’s a lot of vernacular around resilience and personal responsibility. But if you cannot sit in front of an inner city mother who’s lost her second son to homicide and say to her, “If only you could be more resilient, you’d feel better about this,” then right now we don’t have the language. We don’t have the programs. Whether we’re talking about folks in inner-city Chicago, or in Mississippi, or in Vermont, we don’t have that type of program or policy diversification because there’s been a chronic lack of investment. And I believe that’s because we’re not looking at this as a systems issue, we’re looking at it as a personal tragedy.

So it’s not that you’re redefining bereavement, but you’re reconceptualizing it to see it less as something you deal with retroactively and more as something you approach in a proactive way.

That’s absolutely right. I’ll give you two examples. In the U.S. government right now, the Bureau of Labor Statistics collects information on funeral leave. That is conflating an individual experience with a public policy approach. It really should be called bereavement leave, not funeral leave, so that we’re starting to measure who is getting bereavement leave and who is not. There may not be a funeral, and there are many different things that funerals don’t connote.

We’ve made great strides in palliative care and hospice, but I’ve come to believe that’s because it’s largely where white people are dying. If a disproportionate number of U.S. homicides are Black men, and we do not have compassionate death scene investigation practices and policies when that family arrives on the scene, what then? How they are treated, how their child or their brother or their loved one is treated in that moment, correlates to their ability to cope and adaptively process in the aftermath. I’ve talked to many families whose children were not dead when they arrived, but the police were already rolling out a body bag. And they’re saying to the police, “But my son’s not dead yet. He’s not dead yet.”

We don’t tell people who are having a heart attack, “If you take a few more deep breaths and give yourself some rest, you might feel better.” We have systems in place to recognize that this is a fragile individual who’s coming to the scene. We need to make sure that certain protocols are taken to ensure not only their health and well being but, frankly, that we are being respectful to all the people involved in this event. For many families, they’re not seen, they’re voiceless; many are defeated, and they’re often facing systems that are not configured to listen to or acknowledge them in any substantive way.

You succeeded in adding a provision to the budget that encourages agencies of the Department of Health and Human Services to report what they’re doing to advance bereavement care to Congress. What do you hope that achieves?

I would submit that the U.S. Department of Defense and the Department of Justice understand that when a death event occurs, whether it’s someone who’s killed in action or a mass casualty event, this is a very serious event for the family. Bereavement as a health issue and a policy issue is almost entirely absent from the HHS. This provision pushes the directors of those agencies listed to begin examining what they’re doing, if anything, by saying: “You need to begin thinking about this as an issue.” They’ve never done that before. No one has ever asked the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the National Institutes of Health, or the Indian Health Service, what they’re doing on bereavement. And so this is a first step toward making sure that those agencies pay attention and then chronicle what they’re doing on this issue. That’s the first step for something to become a priority.

Mulheron at a donor-hosted event that recognized Evermore for several achievements.

Evermore is also working to get bereavement covered under the Family and Medical Leave Act. What is the significance of that?

We’ll be working on this in 2021. Employment is a major issue — certainly stable employment. Just not getting fired, frankly, in the aftermath of a death event, for just even a few days, would be incredibly helpful to many families. So we’re working on a multi-pronged strategy, setting a national floor on what bereavement leave should look like among small and medium businesses and large-sized employers.

You have a bereavement leave policy on your website, and you’re asking employers to pledge to it, is that right?

We’ve just put the pledge up, and we’re just beginning to share this through our community leadership right now. So there are small, medium and even large-sized businesses that have been in touch with us around using that as the floor. We’ll be working to promote this as a baseline in 2021. The pledge itself and the guiding principles align with FMLA law. So if Congress decides to open FMLA, we have a suggestion for them as they consider any amendment, and then we would be able to align business interests behind this. Congress as a body needs to be listening to its constituents. And if their constituents begin to organize around a central set of principles, it makes the legislative and regulatory process less cumbersome because there’s already adoption and recognition.

You’re also petitioning the White House to create an Office of Bereavement Care. How would having a specific office devoted to this issue make a difference?

The White House office is incredibly important for two reasons. One is that the issue of bereavement spreads across the federal government. There’s no one agency that seems like it would be the best home for that. And it also allows the federal government to coordinate a swift and effective response across agencies, especially considering that we have unprecedented bereavement and death events happening in the U.S. right now.

Mulheron enjoying some backyard fun with her dog, Stark.

You’ve mentioned inequality a few times. How does Evermore hope to address inequality in bereavement care?

Inequality must be infused and embodied in all the different facets of work that we’re doing in order to substantively advance the issue. We’re so fortunate to now have statistics that are looking at this — this is a newer development in the last few years. But we need to be talking to communities across the country. We need to be listening to the voices and experiences of Americans from all walks of life. Hopefully we will learn things that can be channeled into resources, tools, data or programs to address some of the structural inequities in the systems that we face.

And what do you think needs to happen for bereavement to be seen as more of a systems issue than a personal issue?

You need a movement of collective voices that begins holding the politicians and the systems accountable for their actions. I’ll give you an example of a current government recommendation that I find outlandish. When there is a sudden unexplained infant death in a family — these are largely sleep-related deaths — the CDC’s gold standard practice is to have families reenact the death event with a fabric baby doll within hours of the death event itself while being photographed by death scene investigators. Often while Child Protective Services is being called in for their other children. Can you imagine? I’m not saying that infant homicide doesn’t happen, it does happen, but it’s rare. The CDC says it’s a voluntary recommendation, so people can decline. Well, I’ve spoken with families who have declined — and then law enforcement assumes even more that they’re guilty. They confiscate their media — their cell phones, their computers, any photographs or videos of their child are all gone, sometimes for more than a year. How did we get to such a place where we have lost sight of our neighbor and our fellow American, and that this is someone’s child, this is someone sibling, someone’s spouse or parent?

How do you think we got here?

I just don’t think anyone ever took a step back and looked at this as a population-level issue.

Has there been enough formal data collection around bereavement?

There is so much to be done. I often say when it comes to data that this issue is Swiss cheese, there are holes everywhere. No one’s ever looked at trying to correlate all the data and synthesize it into a national plan or discover what a blueprint should look like for research in this area.

Are there any other countries that have policies that the U.S. could draw from?

Absolutely. Whether or not they’re looking at it as a total system issue could be argued, but if you look at Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the U.K., they are certainly more advanced. Canada’s guidance around miscarriage and stillbirth is much more comprehensive than what’s published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which is very clinical. So I think there’s a lot to learn from our international partners, but I’m most interested in hearing from my fellow Americans who’ve been through this experience because how I might experience a system as a middle-class white woman is different than someone who has less income or has a different racial or religious background.

Thank you for sharing your time and insight, Joyal.

Lack of Bereavement Leave and Other Policies Fail Bereaved Families

Lack of Bereavement Leave and Other Policies Fail Bereaved Families

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville