Dr. Micky Golden Moore, Ph.D. M.S. H.P., spent the first 30 years of her professional career helping people from all walks of life find their voice. After completing a doctorate in communication studies at Wayne State University, she traveled between the U.S. and the U.K. as an adjunct professor and consultant, teaching others how to improve their speech writing, public speaking and interpersonal communication skills.

Dr. Micky Golden Moore, Ph.D. M.S. H.P., spent the first 30 years of her professional career helping people from all walks of life find their voice. After completing a doctorate in communication studies at Wayne State University, she traveled between the U.S. and the U.K. as an adjunct professor and consultant, teaching others how to improve their speech writing, public speaking and interpersonal communication skills.

But then a series of personal losses transformed her life and, eventually, her work. After losing both of her parents — first her father to cancer, and then, three years later, her mother to heart disease — Moore felt overwhelmed with grief. Deeply shaken and looking for a way to find meaning in her losses, she followed the suggestion of a friend and entered a master’s degree program in Hospice and Palliative Studies at Madonna University in Livonia, Michigan. There she met her mentor, Dr. Kelly Rhoades, Ph.D, who Moore now credits with “saving my life.” It was through the Madonna University program that she found the strength to pursue a career helping others transform illness, loss and grief.

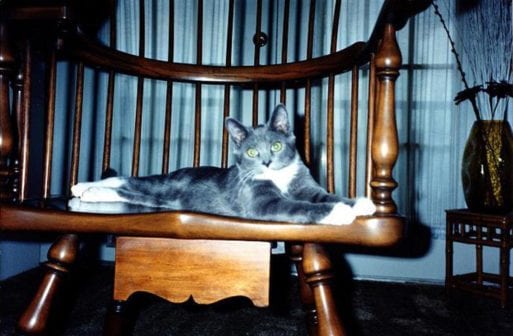

And then came yet another devastating loss — the sudden, unexpected death of her two 16-year-old cats Nellie and Pablo, who died one month apart in 2008. “I was inconsolable,” Moore said, even with the support of husband Bud and colleagues at school. With nowhere else to turn, she used her grief to spur her on to new learning and began investigating the subject of pet loss. But even after authoring several papers on the subject, Moore found herself wanting and needing more. She began searching for pet loss support groups in her area and, finding none, attended a few grief support groups for those who had lost human companions. But these left her feeling even more alone and bereft.

Then one day, as she lamented the lack of support to her professor, Moore got a wake-up call. “In your search for support, ” Rhoades said, “can’t you see that you are the one to provide it!”

That moment catalyzed what happened next.

”I woke up from a dream one night and knew that I was going to form a pet loss support group and what I would name it, “Moore said. “Beyond the Paw Print” — a reference to the clay paw print that crematories provide those who have lost beloved pets — would be a place where grieving pet parents could find solace, companionship and meaning as they shared stories of “love, loss and lessons learned.”

Moore’s beloved cat Pablo, who died suddenly in 2008 at the age of 16.

The group met for the first time at the Orchard United Methodist Church in Farmington Hills, Michigan,on March 9, 2009, and continues to meet monthly today (currently on Zoom due to the COVID-19 pandemic). A compilation of some of the many moving stories shared in these groups is now available in Moore’s first book, “Tails from Beyond the Paw Print: Twenty-two stories of love, loss, and lessons learned from our adored animal companions,” which she published in May 2020 to a host of positive reviews.

Editor’s note: The following interview has been edited for length and readability.

Thank you so much for speaking with me today, Micky. Can we start by talking a bit about why you believe pet loss is minimized by so many people?

I believe many people minimize pet loss because they’re uncomfortable talking about it, just as they are uncomfortable talking about the loss of a person or death in general. When someone who cares about us is confronted by our grief, whether we’re grieving a human or a beloved pet, they want more than anything for us to feel better. But they don’t know what to say to accomplish that. So they say things that are not helpful in the hopes of helping us to “get over” our grief. But grief isn’t something you “get over,” and those platitudes inevitably fall flat.

Pet loss is also misunderstood by many people who have never had a strong emotional bond with an animal. Those of us who have shared that deep personal connection know that losing a pet is no less painful — and is sometimes even more painful — than losing a parent or a sibling or a friend. Human relationships are complex and messy and fraught with drama. But our relationships with our pets are incredibly simple: All we have to do is feed them and care for their most basic needs, and in exchange, they give us loyalty, affection, companionship and joy. For some of us, having a pet may be the first time in our lives that we are the recipient of this form of judgment-free, unconditional love. So our grief is, in a way, a combination of the loss of our beloved best friend and the loss of love in its purest form. That’s hard for someone who has never experienced it themselves to understand.

I’ve read most of the stories in your book, and one of the things that struck me was how people were eventually able to move past their pain and remember the good times they had with their pet. How does Beyond the Paw Print help them accomplish this?

Beyond the Paw Print is, above all else, a safe haven for grieving pet parents to talk about their pet, their loss and their grief. It’s a place where people feel validated and understood and know they will not be judged for expressing how they feel. I act as a facilitator, guiding the conversation and making sure that everyone who wants to share their story has the opportunity to do so. But I also let participants know that sharing isn’t necessary; it’s fine to just sit and listen and, if it feels right, cry. I believe that being in that non-judgmental environment allows healing to begin. And, from the very first day, the people who attend the group have affirmed that for me. In fact, those first 12 attendees were what inspired me to continue this work.

Moore at home in Michigan holding a copy of her book, “Tails from Beyond the Paw Print”

Was that also your inspiration for creating your book, “Tails from Beyond the Paw Print?”

Yes! The idea for my book began to form in the back of my mind after that very first meeting. I felt strongly that others outside the Beyond the Paw Print community might benefit from these stories of love, loss and lessons learned. My objective was to help grieving pet parents learn that they weren’t alone, their grief was real, support was available, and healing was possible.

Equally important, I imagined that these stories, if widely shared in book form, could assist in changing the perception of pet-loss grief. Perhaps we could move the dial a bit from disenfranchised to greater understanding and acceptance. I wanted to write a book for anyone who has ever loved an animal and has grieved their loss or for anyone who seeks to better understand those who do.

Do you have any specific advice for people who may want to support a friend or family member who has lost a pet but doesn’t know how to go about doing so?

Of course! After so many years of supporting grieving pet parents, I have witnessed their suffering when well-meaning loved ones say the wrong thing. So I’ve put together a list of some dos and don’ts that I like to share.

Be present: Show up! Both figuratively, virtually and literally … grocery shop, take out the trash, meet them at the vet hospital or be there when the cremains are delivered. Small acts of kindness can mean so much!

Be quiet: Stop talking and stop trying to fix or cure the bereaved. Allow them time to express their feelings … listen without judgment. We’ve been given two ears, two eyes and one mouth for a reason. Listen more, speak less.

Be kind: Choose your words with care. A simple statement of support, such as “I may not understand your grief, but I care about you and want to listen and support you,” is often all that’s needed to help someone feel that you’re there for them.

Avoid comparing grief experiences: Yes, everyone has their own grief experience, and some are far greater and more impactful than others. But please allow me to have mine.

Avoid unhelpful statements such as “He’s in a better place,” “God needed him more than you,” or “I know exactly how you feel.” (You don’t!)

Avoid a judgmental tone or callous statements, such as:

“It was just a cat!”

“There are thousands of animals in shelters, go adopt another one!”

“You’ve been grieving for weeks, there’s something wrong with you!”

“You’re crazy! You need help!”

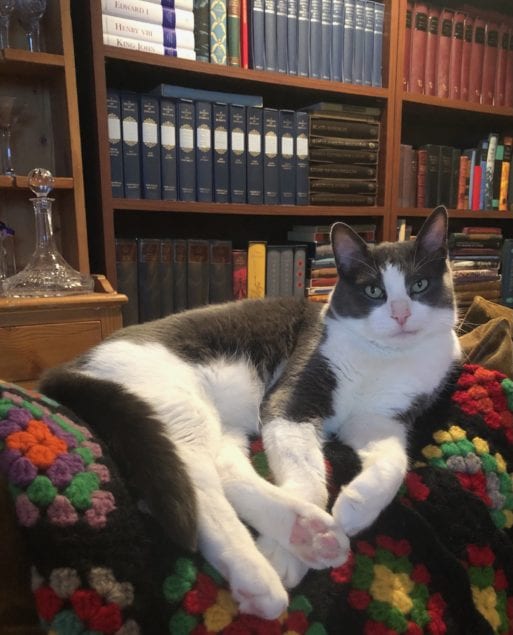

The most recent addition to Moore’s pet family, Cornwall, is named after her favorite part of England, the southwest corner of Cornwall.

My last question has to do with helping grieving pet parents cope with their loss, especially today when so many of us are isolated due to precautions around COVID-19. Do you have any suggestions that might help ease the pain of pet loss and help grieving pet parents move through grief with a little more ease?

I do. While there’s no “magic bullet” that will work for everyone, I’ve found that these kinds of activities have helped our Beyond the Paw Print community find comfort and meaning in their grief:

Seek out a support group online or among caring friends.

Commission a local artist to create a pet portrait.

Create a memory book or photo album.

Designate a special shelf or cabinet for placement of your urn, photos and other keepsakes that remind you of your pet.

Write a story about your companion and share it with friends and family or on a personal blog or Facebook page.

Write a letter to your companion. Then, write a reply from your companion to you.

Create a keepsake. Search online for keepsake necklaces, bracelets or rings to hold a small portion of your pet’s ashes.

Create a memory garden in your yard. Plant special flowers or a tree in a dedicated area and name it after your pet. Mark the spot with a small stone plaque if you wish.

Hold a memorial service or remembrance event. Invite friends and family who also loved your companion and include whatever feels natural to you — music, storytelling, poetry, prayer, candles or anything else that reminds you of the love you shared.

Thank you so much, Micky, for these truly helpful suggestions and for sharing your time and expertise with our readers and with me. It’s been a real pleasure speaking with you.

You’re very welcome, Kathleen.

Pet Loss Support Group Offers Comfort to Grieving Pet Parents

Pet Loss Support Group Offers Comfort to Grieving Pet Parents

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?