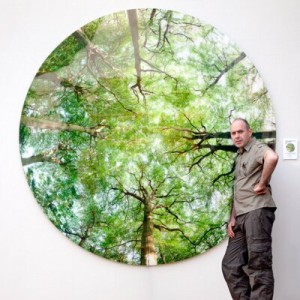

In part two of a two-part interview (read part one here), SevenPonds speaks with the Dublin born, UK based photographer David Anthony Hall. David’s work inspires its viewer to reflect upon his or her relationship with the natural world and his sprawling photographs of woodlands have been recognized worldwide. But amongst his proudest achievements is his work’s relationship to hospice environments and cancer research. Through permanently installing his work in hospice centers (such as Marie Curie Hospice in the West Midlands, UK), he has consequentially become a pioneer of sorts in an important mission: to make hospices not just inhabitable, but uplifting.

MaryFrances: What are your hopes for future hospices in relation to the integration of more creative, artistic outlets for well-being?

David: Generally the thing about new hospices here in the UK is they only ever budget for the building delivered with the walls painted white! They don’t budget for art, which means work needs to be retrofitted. This holistic creating-an-atmosphere approach is either not considered, has no funding or is left to individual self-employed artists to supply work free of charge. I hope to lead by example by showing how important art is in the context of their buildings. It’s important, for this to happen, that there are no budget constraints. As where money is involved, compromises have to be made and often it is these compromises that add up to deliver poor hospice environments, thus adding to the problem. I want people to build the art with the buildings, for it to be a collaboration — to conceive and build the pictures into the walls. Not only does that save cost but it opens up the possibility of collaboration with architects, staff and patients.

MaryFrances: Can you recall a moment when you really started to reflect about death, or the “bigger picture” of things?

David: My gran (Ellen McEvett 1900 – 1981 RIP) died on the 16th January 1981. Two days later, on my birthday, she appeared at the foot of my bed. Growing up in Catholic Ireland, there was this unspoken notion that if you “did everything right,” everything would “be alright.” Losing Margaret when I was so young really impacted me – she was such a young, healthy girl — and it was the beginning of many experiences with cancer for me, of being in hospice environments to support those I love.

As our lives advance at certain stages, we become more aware of things. For me, I think it was also having my kids. When my dad passed away (Bernard (Brian) Hall 1931 – 2013 RIP), my five year old son said rather matter-of-factly, “Grandad is extinct.” It really struck me, because he could comment on it so frankly. In the context of our lives, things affect us, but it’s only at certain stages in the journey when we become more aware of ourselves.

MaryFrances: How did you decide on which photographs to put into the hospice facility? Was the focus on trees and the natural world something that had already interested you?

David: It’s all intertwined. Like I said, for quite a while I had stopped taking pictures. When my biological father was diagnosed with cancer, I used my photography as a kind of cover for my motives, that to be available to support him during his treatments without seeming overbearing. I wanted to be there for him, especially as I knew he wasn’t coping well. I could travel to see him on the pretense of taking pictures.

I would go to see him in the hospital, and then I’d head off to the woods to take pictures. And that’s the heart of the connection: the antithesis of being in the hospital was being in the woods. It can be a spiritual place, I think. A retreat. You know, research is showing that even glimpses of nature for medical facilities can help patients with healing and attitude – and I can definitely relate to that. I think that’s why my images work so well in a hospice environment.

MaryFrances: What would you say to those who think art is an afterthought when it comes to hospice design?

David: Well, consider this: you present yourself at the hospices in wintertime, and regardless of the new and wonderful hospices that are being built with gardens, there are inevitable seasonal changes. In the winter, it’s pretty awful. In the rain? Also awful. With my photos, you’re allowed to have spring 365 days a year. You’re creating an inviting place. And I think it’s good for the staff of the hospice – of course the clinical equipment available is most important to have, but what about the atmosphere of the place? I think it also shows a kind of respect for the staff, helping to transform their working environments with the power to take their walls outside. For accompanying adults and visitors, my images are uplifting, providing a calming and soothing distraction.

MaryFrances: What has working with nature taught you about mortality?

David: It has grounded me in a good way. You realize that everything dies in the fall and is reborn in the spring. As more and more of us move to cities, we lose touch with nature’s ways. It’s natural for us to die. It’s a miracle for us to be born. We are all made of stardust.

There’s a feeling in Ireland where we celebrate funerals and cry at weddings (laughs), but I really do think it is good to celebrate someone’s life. No matter how close we are to someone who’s passed, it shouldn’t be such a debilitating reality to the people who are left behind – because that’s just it, it’s a natural reality.

MaryFrances: It’s a very humbling and comforting experience.

David: Being in nature helped me make sense of what was happening. The woods can be a wonderful metaphor for human nature, I think. When a forest evolves, new space has to be made for light, otherwise nothing is going to grow there. Trees have been around for hundreds of millions of years, [they’re] time-travelers, really! They’ve shaped us and our planet. They fulfill our basic needs for survival. They allow us to breathe; they recycle our water and store our carbon. They are the raw material of both construction and fuel, and they are symbols of our relationship and weight on the earth. Furthermore they’ve taught me to look at my life and human existence in a greater context.

MaryFrances: Thank you, David.

David: Thank you.

What Do Trees and Hospice Centers Have in Common? An Interview with David Anthony Hall, Part Two

What Do Trees and Hospice Centers Have in Common? An Interview with David Anthony Hall, Part Two

Funeral Home Owner Chris Johnson Spending Halloween in Jail

Funeral Home Owner Chris Johnson Spending Halloween in Jail

Our Monthly Tip: Toast a Loved One with a Personalized Glass

Our Monthly Tip: Toast a Loved One with a Personalized Glass

My Cousin’s Death Taught Me the Meaning of Life

My Cousin’s Death Taught Me the Meaning of Life