Today SevenPonds speaks to Akhila Murphy, a trained death-care midwife who has been practicing since 2013. Murphy’s job is to help families create beautiful personalized memorial services for loved ones inside their own homes. In this first part of our two-part interview, Akhila discusses the fundamental responsibilities of her job, the path she took to become a death-care midwife, and her ideas for the future of the profession.

Credit:www.star-telegram.com

Kristen: Can you describe what your job entails?

Akhila: Being a death-care midwife means that I work to inform people about end-of-life and after-death options. This might include guiding a memorial service for a loved one who has died and/or offering ideas as to conducting home funerals and green burials. Most people don’t realize that home funerals are legal in all 50 states. This means families have the right to care for their loved one in the privacy of their own homes.

Death-care midwives encourage people to create a comfortable atmosphere in their homes for the dying. We help guide families through the dying process and assist in preparations for a home funeral. Death care midwives may sit vigil with a loved one or suggest how to arrange different grief rituals, such as decorating the casket, dressing the body or preparing the body to lie in honor.

These loving practices really bring into question why we stopped caring for loved ones at home in the first place, which they still do in many other countries. Our job really is to encourage families to bring back the tradition of caring for their loved ones at home during dying, and to complete the care with home funeral and disposition such as green burial. We’re really looking to change the paradigm.

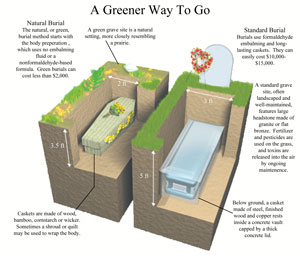

Kristen: What are green burials?

Akhila: A green burial is a way for someone’s body to return to the earth once they have died. It’s actually been practiced for thousands of years, and, if done right, does the least amount of environmental damage. The body is buried without the use of a cement vault. Embalming is not required. The body can be placed in an eco-friendly casket made of wood, cardboard, or bamboo, without toxic glues or nails, or be wrapped in a shroud. The person is placed directly into the grave so that decomposition can happen naturally. After the body is buried, usually family members like to mark the place of the burial.

Most green burial cemeteries are an environmentally friendly setting without lawns, which require fuel burning mowers and the use of pesticides. They may allow people to leave a simple marker such as an engraved natural stone, or use GPS coordinates to mark the graves. It’s a really beautiful tradition.

Green Burial vs. Traditional Burial

Credit: www.natwincities.com

Kristen: Can you mention some specific differences between a conventional funeral and a home funeral?

Akhila: Sure. Most of the home funerals I guide take place in either the person’s home or a relative’s home, rather than at a funeral parlor. It’s interesting because, in our great-grandparents’ day, they had rooms called parlors that were specifically designated for laying out a loved one’s body so visitors could come and pay their respects. With this old tradition, families were in charge of completing their loved one’s death care process.

Home funerals allow family and community to spend as much time as needed with the loved one who has died in a comfortable, familiar environment. With conventional funerals, a mortician processes the body and only allows a limited amount of time for the funeral service, which happens in an unfamiliar setting, such as a mortuary. Allowing for extra time with the loved one gives families time to process that their loved one is gone, which helps the grief process. They may also create their own ceremonies, which may include singing songs, telling stories, washing and dressing the body, and creating a sacred space using their own religious or spiritual traditions. Death-care midwives, also known as home funeral guides, are there to guide them through the process and support the grief they feel while taking care of their loved one. It really becomes a sacred space for all involved.

Kristen: How did you get started in the practice?

Akhila Murphy

Credit: Akhila Murphy

Akhila: Before becoming a death-care midwife, I volunteered in hospice, which is where I became very interested in the process of how people should be cared for at the end of life. Then I took a training class with Final Passages, which is a program developed by death-care educator Jerrigrace Lyons, who has been offering training in home funerals for nearly 20 years. The training is a two-part session covering two five-day weekends. We participated in role playing, watching death-related films, listening to guest speakers and learning about creating sacred space. We also learned how to completely care for a body after death, how to have the person lie in honor, and how to consult with families about our work. Lastly, we learned about being a guide, and how to be an educator and supporter of all aspects of death and dying, including knowledge of different laws and what paperwork needs to be filled out.

After completing the training program, I co-founded an organization called Full Circle Living & Dying Collective, which works to educate the community about all aspects of death and dying; encourage conversations about death and advance planning; and guide families through their own home funerals.

Kristen: Would you say being a death-care midwife is a job most people know about?

Akhila: Not at all. It’s not something that is known because people usually avoid conversations about death and dying. But I think it’s a subject that should be talked about more. Through Full Circle Living & Dying Collective, we’ve been engaging the public in conversations about death and letting people know that they can create their own support system so they don’t have to go through the dying process alone.

Credit: grievinganthony.com

Kristen: What do you feel is the most rewarding aspect of being a death-care midwife?

Akhila: I would say the most rewarding aspect comes after I tell people about the possibility of having a home funeral for their loved one, and their faces light up with surprise. I just love when people’s eyes are wide with wonder, like “What? You can actually do that?” It’s also very gratifying seeing the people who come through the process. The fact that they gave their loved one a home funeral and/or memorial filled with love and compassion is very rewarding, and they feel enthusiastic about it as well.

Kristen: That’s really inspiring! What would be the hardest part of your job?

Akhila: On the business side of things, there are difficulties spreading the word about home funerals, which entails a lot of marketing and teaching others about the process. Getting the information out there and framing it in a way that people want to come and listen about these options is always a challenge.

Personally, the hardest part has been controlling my emotions. I am a very emotional person, and I do cry easily, so it is definitely hard to hold back and maintain a professional demeanor when I see a family in grief. I don’t mind sharing tears, but I do like to make sure I remain a professional guide for the families hosting the service.

Kristen: I can understand that; you are being strong for others. Would you say you notice a difference in the way children and adults handle these situations?

Credit: hansenspear.com

Akhila: Yes. Children actually handle it better than adults most of the time. I feel as if children are more curious and not as fearful of situations until adults express their own cues of fear, projecting them onto their kids subconsciously. Kids might reach out their hand to touch a loved one who has died, and ask why it’s cold, whereas adults may feel uncomfortable just being in the same room with the person. It goes back to our culture in general and the widespread death-phobia phenomena. Most people in our culture have never discussed plans for their own funerals with family or friends. There’s a sort of superstition that if we talk about death, we must have some death wish, or the discussion will bring about death. Children can actually be teachers for their adult family members by asking these important questions and trying to get honest answers.

Kristen: How many hours a week would you say you work?

Akhila: Actually, we are currently growing our services and spreading the word, so we only do about three to four home funerals a year. I cannot really accurately calculate the number of hours per week. Our organization, Full Circle Living & Dying Collective spends a lot of time getting the word out by sending email newsletters, social media, creating presentations, and hosting speakers, such as a recent talk with our local cemetery district. We host free community events, such as showing death-related films, demonstrations of home funerals, private consultations to discuss home funeral options and advanced planning, and organizing Death Cafés and group conversations about the topic of death. We also participate in our community’s local Altar Show, which commemorates the Day of the Dead on November 1st.

Kristen: Do you support the practice of physician-assisted death?

Akhila: While I don’t think that it is for everyone, I do believe that it should be legal. California recently passed the End-of-Life Options Act, which gives people control over their lives and deaths. There are careful safeguards in place that only allow persons with a terminal diagnosis who is of sound mind to request the prescription from their doctor. Only the patient may administer the dosage, not the doctor or anyone else. I feel that each person should have the right to die as they feel appropriate, whether that means abiding by their own faith tradition, or consciously deciding to discontinue life when it becomes unbearable.

Kristen: Before we close, is there anything you want those caring for a dying loved one to know?

Credit: guideposts.org

Akhila: It is most important for the caregivers to take care of themselves. I recommend that they get as much help as possible to support their staying healthy during the difficult time of caring for a loved one who is near the end of their life.

Ask for help, and take it when people offer it to you. Check in with your doctor about hospice care. Also, make sure to check in with your community; there may be options to hire caregivers that specialize in end-of-life care.

Be sure there is an advanced directive in place and that the wishes for the dying loved one are documented. Have meaningful conversations about dying, death, funerals, and memorials with family, and try to help the dying person come to terms with unresolved issues.

Also, recognize that grief is not an illness. It is a natural response to loss and death. Grief is a deep form of love, and it needs to be acknowledged.

Lastly, I would like people to know that they have the legal right to care for their loved ones in their own homes both before and after death. In most states, you can be your own director of the funeral, but make sure to look up what the laws are in your area before you proceed.

What is a Death Care Midwife? An Interview with Akhila Murphy

What is a Death Care Midwife? An Interview with Akhila Murphy

“Hand to Earth” by Andy Goldsworthy

“Hand to Earth” by Andy Goldsworthy

Trans Remembrance Project Provides a Community of Grieving

Trans Remembrance Project Provides a Community of Grieving

Caring for a Dying Loved One? Be Gentle With Yourself.

Caring for a Dying Loved One? Be Gentle With Yourself.