Early detection works

Credit:archive.wired.com)

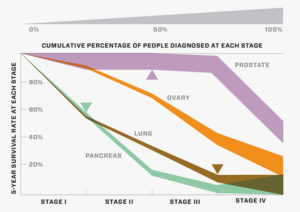

Early detection is one of the most important factors in the successful treatment of many cancers. Since the 1950’s, when the PAP smear for cervical cancer screening became widely available, the death rate from cervical cancer has decreased by over 70 percent. When colon cancer is detected early, the five-year survival rate is over 90 percent. But that number drops to less than 15 percent if the cancer is not found until it after it has spread. Similarly, cancers of the pancreas, lung, breast, and ovaries carry a far better prognosis if treatment is started early on.

But catching cancers early has proven to be a major challenge for the medical community, despite significant advances in cancer screening techniques. For a variety of reasons, many patients still shun the procedures that could save their lives. What’s more, early detection of some cancers is extraordinarily difficult because their symptoms are so obscure. In many cases, neither patients nor their doctors have any clue something is seriously wrong until a cancer has spread to multiple organs. At that point, it’s often too late.

But now there’s a unique — and quite effective — early detection system in the works — the canine nose. In more and more studies, dogs are being taught to identify cancers correctly based on nothing but their sense of smell.

Credit: dogs.thefuntimesguide.com

Take Tsunami, a 3-year-old German shepherd who’s participating in a study at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine in Philadelphia. Tsunami “volunteers” at the Penn Vet Working Dog Center, where researchers have been training her and other canines to sniff out ovarian cancer since 2013. Using a device called a “scent wheel,” scientists introduce various substances, including plasma from cancer patients, noncancerous tissue and “distracting” scents, to the dog. Thus far, Tsunami has been able to detect cancers 90 percent of the time.

Nor is the Penn Vet research the first of it’s kind. In a study reported in the journal Integrative Cancer Therapies in 2013, researchers successfully trained five household dogs to detect lung and breast cancers simply by smelling a patient’s breath. They first trained the dogs over several weeks using breath samples from 55 lung cancer patients, 31 breast cancer patients, and 83 healthy controls. After training was complete, they exposed the dogs to breath samples from different subjects whom neither the dogs nor their handlers had ever met. Some of these people had cancer, and some did not.

The results were impressive. In lung cancer patients, the dogs’ ability to detect cancer was 99 percent, identical to that of a conventional biopsy. In the breast cancer group, it was 88 percent. More importantly, the diagnostic accuracy was “remarkably similar across all four stages of both diseases.” In other words, the dogs were able to detect cancer in its early stages, when treatment is most likely to effect a cure.

Tsunami at work

(Credit: Penn Vet Working Dog Center)

Similar studies have shown that dogs can detect prostate cancer in urine and malignant melanoma by sniffing a mole.

How do canines detect cancer with such accuracy? The simple answer is that a dog’s sense of smell is mind-bogglingly acute. According to researcher James Walker, the former director of the Sensory Research Institute at Florida State University, it is about 10,000 times more powerful than our own. Translating this into concrete terms, he says, “If you make the analogy to vision, what you and I can see at a third of a mile, a dog could see more than 3,000 miles away and still see as well.”

Still, the scientific community remains skeptical, if for no other reason than the idea of using dogs in lieu of sophisticated medical testing seems, to put it bluntly, weird. There are also legal challenges: Who will a patient blame (and sue) if a dog misses a cancer diagnosis, or diagnoses a cancer that really isn’t there?

To overcome these obstacles, the researchers at Penn Vet and other centers around the world are using the canine “sniff test” to identify exactly what volatile organic compounds dogs detect when they encounter a cancer’s scent. If they can determine what these substances are, their chemical signatures can be identified by mechanical means. This may lead to a much more “scientific” early detection system. With a little luck, it may be just as accurate as a dog’s incredible nose.

Can Dogs Really Detect Cancer?

Can Dogs Really Detect Cancer?

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”