Conservationists have recently released blue-tailed skinks back

into the wild on islands in the Indian Ocean.

Credit: Parks Australia

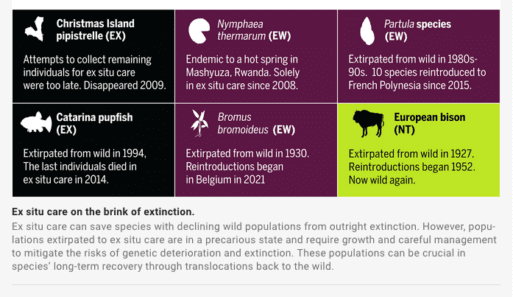

Urgent international effort has the potential to reverse species extinction, a new study has found. The research, published in the journal Science, found that species considered extinct in the wild — which only exist in captivity or other areas outside of their natural habitat — have experienced some population revival through conservation efforts. Species that have been successfully reintroduced into the wild include the Jaramago de Alborán, the Yarkon bream, and the European Bison. Others, including the St. Helena olive and the Pinta giant tortoise, have gone extinct in the past decade.

The study identified and examined the conservation history of 95 species (52 plants and 43 animals) identified as extinct whether in the wild or maintained in ex situ, or human care since 1950. Of these, the International Union on the Conservation of Nature named 72 (33 animals and 39 plants) in the extinct-in-the wild category of its 2022 Red List.

Authors noted that “28 to 48 extant (existing) bird and mammal species would have gone extinct between 1993 and 2020 were it not for actions such as habitat protection, translocation, and ex situ conservation using breeding facilities and zoos.” Meanwhile, “ex situ conservation using botanic gardens and seed banks has also been used to support the restoration of at least eight plant species and populations that had disappeared from their indigenous range.” However, conservationists have only attempted to translocate about 65% of animal species and one quarter of plant species that have gone extinct back into the wild, they said.

Some species maintained by humans are surviving, while others have gone extinct.

Credit: Science.org

“The loss of these species can have a ripple effect on entire ecosystems, and if we don’t take urgent action, the consequences could be catastrophic,” co-author Carolyn Hogg said in a Phys.org article published by the University of Sydney, where she is part of the School of Life and Environmental Sciences. “This study highlights the need for the conservation and academic communities to better apply research findings into practice to maximize the survival rate of individuals when released back into the wild.” Authors urged management plans for ex situ populations that include reintegration into their natural habitats.

Accelerating rates of species extinction have been contributing to widespread climate grief among Earth’s inhabitants as the atmosphere continues to warm and extreme weather events intensify. This study indicates that a heightened focus on the conservation and rewilding of species that have gone extinct in the wild, in addition to addressing those that are endangered, could prevent further grief, loss and ecological destruction.

Preventing Species Extinction Through International Collaboration

Preventing Species Extinction Through International Collaboration

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying