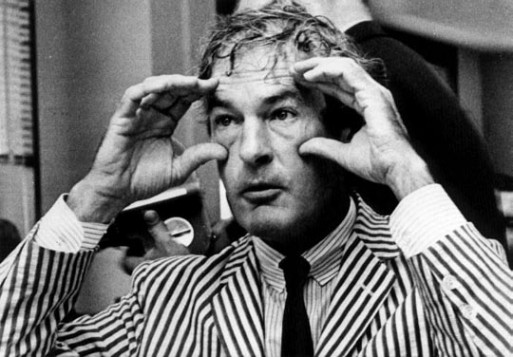

Dr. Timothy Leary, a pioneer and often infamous figure during the psychedelic days.

(credit: Wikipedia)

In the wake of the 1960s, the US government cracked down on its message to the public regarding the use of psychedelics. They hoped to create an image of it as a damaging, dangerous drug. On one hand, their concerns were incredibly justified: the use of mescaline, psilocybin and other hallucinogens can put one’s mind and body through a very detrimental and unsafe experience. Yet, with this harsh stigmatization, the country also brushed aside an important discussion on the positive medical potential for psychedelics. Today, a group of scientists are trying to explore psychedelics’ possibility to heal addiction and depression – and ultimately save lives.

Before its emblematic role in the flower-power scene, psychedelics in the US were observed in a rather academic light. Aldous Huxley was fascinated by the healing, calming properties of mescaline (particularly for those who were in the midst of the dying process). But once psychedelics became so inextricably bound to the ‘turn on, tune in and drop out’ culture, they became more and more difficult for scientists to study (the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 declared psychoactive drugs “void of any medical use” by categorizing them as Schedule I substances).

By contrast, the years preceding the act saw an abundance of papers – 1000 or so – on the positive effects the drug could offer to someone with an addiction or illness. It’s exactly what scientists at Imperial College’s Neuropsychopharmacology Centre in London are hoping to explore in their attempt to help those with clinical depression:

“[It’s] the idea of Professor David Nutt and Dr Robin Carhart-Harris at Imperial College. They argue that psychedelic drugs could prove beneficial to millions of people and that it is time to end the 50-year stigma surrounding their therapeutic use. Nutt and Carhart-Harris have already used MRI scanners to study changes in the brain while 15 volunteers took psilocybin. A similar study on 20 volunteers given LSD has just finished.”

–The Guardian

“It was quite stark how similar [the effects of psychedelics were] to the existing treatments for depression,” said Carhart-Harris, “These drugs are powerful and the therapeutic model we are going to adhere to is quite specific in that it emphasises that the drug needs to be taken in the right environment and with the right support. We have professional psychotherapists there who are trained.”

But how exactly does the use of a substance infamous for its catalyzing of ‘bad trips’ become such a positive agent for healing the human brain? After all, brains on psychedelics become much more chaotic – but that, explains Carhart-Harris, is precisely the point. “Parts of the brain that would not normally communicate with each other link up,” he explains, “[and] in this disorganised dream-like state, the brain is open to new leaps of creativity and flights of fancy…hallucinogens may temporally “loosen” the rigid structures of the brain, which have developed as we age. An acid trip is a bit like shaking up a snow globe. This loosening could help the brain break the cycles of addiction and depression.”

You may enjoy:

- The Guardian’s in-depth article on the above study

- An “Intelligent Form of Dying”: Aldous Huxley’s Psychedelic Death

- How Psychedelic Drugs Can Help Patients Face the End-of-Life

Tune In: Could Psychedelics ‘Break Down’ Depression?

Tune In: Could Psychedelics ‘Break Down’ Depression?

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?