A recent New York Times article, “An Online Generation Redefines Mourning”, opens with the story of a twenty-something who requested a picture of his mother sent through text message. That way, he wouldn’t have to identify her remains in person. Tweets of L’wren’s recent suicide often came with the hashtag “RIP”. Funeral selfies are in vogue. And who among us hasn’t visited a lost loved one’s Facebook profile? Who hasn’t seen new posts on his or her wall from everyone else who had the same idea, the same curiosity? How do technology, the internet and social media affect the way we grieve and die?

One way is by creating a safe space for us to talk about these historically private experiences. At SevenPonds, we celebrate the internet’s tools for communicating, building community and fostering dialogue. And elsewhere, many people—mostly the young and tech-savvy—are “starting blogs, YouTube series and Instagram feeds about grief, loss and even the macabre, bringing the conversation about bereavement and the deceased into a very public forum.” Two phenomena balance each other: talks on death relax in these casual social channels and social media becomes a socially acceptable place for grief and pain.

Modern Loss, an online community founded by Gabrielle Birkner and Rebecca Soffer, exemplifies the balance between death’s severity and social media’s levity. While providing “emotional and psychological support resources for people in their early adult life-stage,” the “about us” section crackles with wit and humor: “Stay tuned for upcoming Modern Loss events in real life. Because misery loves company, and nachos. And margaritas.” With candid stories on loss come interesting, but relatively minor, “21st century topics like what to do when Gmail keeps suggesting someone who has died as a contact.”

Two phenomena balance each other: talks on death relax in these casual social channels, and social media becomes a socially acceptable place for grief and pain.

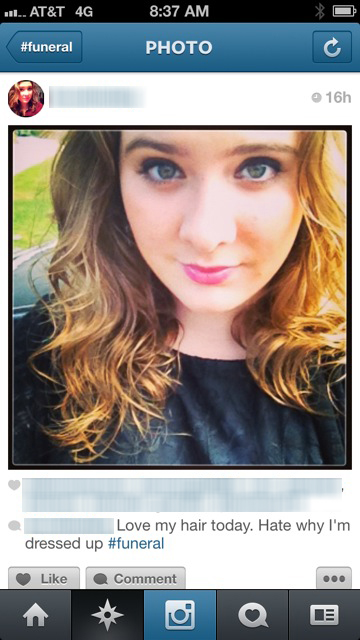

While Soffer and Birkner’s website sustains a balance, at least one suitable for the Millennial sensibility, how do other forms of social media bear the weight of death and grief? How much emotional depth can social media support? As Ms. Birkner says, “It’s not the nature of social media, generally, to react thoughtfully to things and think, ‘How can I really help?’ It would be great if everyone said, ‘Can I buy your groceries, or can I start a meal train?’ ” “Performative grief”, an insidious blend of grief and narcissism, turns sacred, life-changing experiences into opportunities for a tweet that might go viral or a facebook post that might achieve a record number of “likes”. (Facebook actually considered introducing a “sympathize button”, though nothing came of it.) If Facebook provides a medium through which one’s private emotions can find resonance and relief in those of others, the dangers of self-dramatization abound.

But I’m not convinced that social media created these dangers. I’m reminded of Ophelia’s burial scene, where Hamlet and Laertes compete with each other to see who can express the greater grief by mourning the loudest. It’s horrific. They leap into her grave. What should be compassion for Ophelia becomes a chance for each young man to demonstrate his emotional depth by showing how much grief he can bear.

If Facebook provides a medium through which one’s private emotions can find resonance and relief in those of others, the dangers of self-dramatization abound.

The dangers surrounding the way we perceive death have always persisted. Hamlet and Laertes demonstrate how not to use social media for grief and dying; the problem is not the social media itself, but how we use it. Sure, a tweet riddled with abbreviations and hashtags may cause harm through an attempt to convey a message too emotionally fraught to carry with it a message of due respect, and a picture via text may be a deplorable substitute for a mother’s real remains, but hasn’t death always been too difficult for words? What is the alternative? To shut off all these conversations and conveniences because they’re not formal or delicate enough? Silence may be the worst we can do. Meanwhile, we’ll keep writing, whether we are delicate or not.

More from Something Special:

How Does Social Media Affect the Way We Grieve?

How Does Social Media Affect the Way We Grieve?

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?