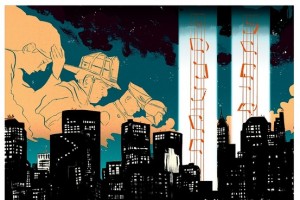

By Ryan Inzana

With the approach of the ten-year anniversary of 9/11, 2001, many will ponder what our country has learned in the last ten years. 9/11 was perhaps America’s first “existential” moment since the Great Depression — we were reminded that our nation was in fact still threatened by the same powerful, destructive forces that threaten the rest of the world. Our artistic representations of the events of that fateful day should be a useful way to chart our culture’s progress. Perhaps it is noteworthy that, as of yet, there has been no definitive, significant film, book, or work of art or music that addresses the subject.

This is not for lack of trying. There have been many films about first responders and New Yorkers’ experiences. Documentarians have chronicled the aftermath and the various manifestations of the fall out. Modern classical composers have also contributed their responses, most of them impenetrably dark and abstract works, such as John Adams’ haunting “On the Transmigration of Souls,” the most celebrated of them.

In a tongue and cheek 2010 article, a British writer for the Guardian’s Film Blog compares the progression of Hollywood’s 9/11 films to the Kübler-Ross “Five Stages of Grief” model: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Early, perplexed films such as Spike Lee’s 25th Hour could be interpreted as symptoms of denial. Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11, gives us anger. Remember Me, a terrible 2010 romantic comedy in which the attacks act as an end-of-film plot twist, might have been Hollywood’s “acceptance”: as the writer puts it, “love means you never have to say your sorry for an exploitative ending.” Perhaps the best film on 9/11 is also one of the simplest: United 93 tells the straightforward story of the eponymous flight that crashed in Pennsylvania after the passengers overpowered their captors. Perhaps this indicates that the enormity of the event has been too much for our culture, or at least our film producers, to fully process.

If this is the case, where in the Kübler-Ross model are we? If we are to take our national response, entry into the Iraq War would be an obvious candidate for our period of “anger.” Perhaps the war-weariness that followed, and President Obama’s conflicted escalation of the war in Afghanistan, would be our period of bargaining. Maybe this means that we will soon be forced to realize our limitations, that no matter what we do, death on a national scale will always be a risk, just as it is to everyone else in the world, our period of “depression.”

A Painting of Ground Zero, Compiled in the National Memorial's Artists Registry

So what will it look like when we’ve reached acceptance? Maybe something like the National Memorial that will open at Ground Zero this Sunday, with its sense of inclusive, ubiquitous loss? Or the still-under-construction Freedom Tower, which upon completion will dominate the Manhattan skyline near to the same extent that the Twin Towers did (and whose name, in this writer’s opinion, is uncomfortably evocative of our denial, anger, “freedom fries” phase). Europeans, after all, have to live with the legacy of WWII, a catastrophe whose genesis lay almost solely within their own borders. How did they do it? We Americans may have no choice but to find out. And who knows, maybe this will do us some good.

9/11 in Art

9/11 in Art

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?