Persons with dementia are being labeled schizophrenic to justify the use of potentially deadly antipsychotic drugs

The use of antipsychotic drugs in the elderly has long been recognized as dangerous. Studies have shown time and again that elderly patients treated with antipsychotics, especially those with dementia, are nearly twice as likely to suffer a serious health event as similar individuals who don’t receive such drugs. This is true of newer atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone and Nuplazid, which carries a “black box warning” that states “Elderly patients with dementia treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death.” It’s also true of older antipsychotics such as Haldol. Nonetheless, U.S. nursing homes have been indiscriminately prescribing both typical and atypical antipsychotics to “unruly” residents for years.

The practice and its deadly consequences finally came to the attention of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the mid-2000s, when reports of adverse events due to the use of antipsychotics in nursing home residents peaked. Tasked with the oversight of the nation’s nearly 16,000 nursing homes, CMS in 2012 devised the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes. The initiative had three goals: to increase education and outreach about the dangers of antipsychotic use in elderly persons with dementia; to gather data about the inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs in nursing homes; and to update quality standards so that nursing homes that over-prescribed antipsychotic drugs could be monitored and, when necessary, disciplined. The results would also be publicly reported and incorporated into the “star rating” of each nursing home.

Unfortunately, the new standards contained a gaping loophole. The reporting requirement did not apply to nursing home residents who were diagnosed with schizophrenia, a disease for which antipsychotics are more or less required. So now, not surprisingly, the number of nursing home residents with a diagnosis of schizophrenia has skyrocketed by over 70%. What’s more, according to a 2021 report from the Office of the Inspector General, fully one-third of those residents had no Medicare service claims for that diagnosis prior to their admission to a long-term care home.

Many nursing home residents are given multiple antipsychotic and psychoactive drugs

Today, one in nine nursing home residents in the U.S. has a diagnosis of schizophrenia — a condition that appears in about one in 150 of the general population, according to a New York Times report from September 2021. Further, as the OIG suggests, few of these patients had a history of schizophrenia before winding up in a nursing home. They are not elderly persons who were diagnosed with schizophrenia at 35.

“People don’t just wake up with schizophrenia when they are elderly,” Dr. Michael Wasserman, a geriatrician and former nursing home executive, told the Times. “It’s used to skirt the rules.”

Dangerous and Illegal

Despite its widespread acceptance, drugging nursing home residents into a subdued and manageable state is almost certainly illegal in addition to being dangerous. According to Charles Patrick Davis, M.D, Ph.D. writing for MedicineNet, chemical restraint is only warranted in severe cases of agitation in which a person is a danger to themselves or others, and their behavior can’t be controlled in any other way. What’s more, it should never be used to control the symptoms of dementia, which can include behaviors that are difficult to witness and stressful to staff but don’t rise to the level of a medical crisis requiring restraint. Some people with dementia do become violent, but that’s hardly the norm.

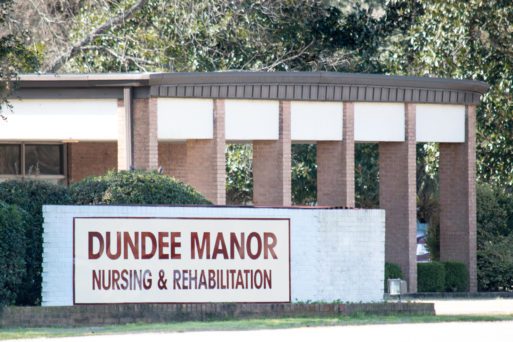

And yet the practice continues, with often devastating results. Many nursing home residents on antipsychotic medications become so sedated that they develop bed sores or pneumonia from sleeping all day. Others simply stop eating and waste away from malnutrition, while others suffer cardiac complications or strokes. Like David Blakeney, 63, who was a resident at South Carolina’s Dundee Manor nursing home and was prescribed Haldol and Zyprexa after staff asked his doctor to add a diagnosis of schizophrenia to his chart, many of them wind up dead.

The Dundee Manor Nursing Home in Bennettsville, South Carolina

A sturdy 205 pounds before he began receiving antipsychotic medication at Dundee Manor, Blakeney was just 128 pounds at the time of his death. “Consider medication adjustment,” a dietician wrote in his chart, noting that Blakeney was “sleeping all day and through meals.” When Blakeney was admitted to the hospital shortly before his death, the hospital physician was so alarmed by his condition that he wrote: “Hold the patient’s Ambien, trazodone and Zyprexa because of his mental status changes.” He then added, “Hold his Haldol.”

But when Blakeney returned to Dundee Manor, the medicines were resumed. Shortly thereafter, while his daughter searched for another facility to care for him, he died.

Balancing Profits and Safety

Understaffing, low pay, poor training, and high staff turnover are chronic issues in today’s nursing homes, and the COVID-19 pandemic has without a doubt made them much worse. Nursing home employment in the U.S. dropped by over 200,000 in 2020, according to the Times, while antipsychotic use rose. At the same time, fewer government inspectors have been available to monitor antipsychotic use, and those who are seem reluctant to report that the violations caused “actual” harm. As a result, nursing homes who sedate vulnerable patients with antipsychotics suffer almost no consequences, and CMS continues to report that its efforts to curb the abuse are working when, as a matter of fact, they’re not.

Jim C. Scott, CEO of Alliance for Aging Research

Meanwhile, powerful lobbyists from the nursing home and pharmaceutical industries are pressuring Congress and federal regulators to weaken existing protections and broaden the list of conditions for which antipsychotic drugs can be prescribed without public disclosure. In a statement on the website of the nonprofit Alliance for Aging Research, which is coordinating the lobbying effort, CEO Jim C. Scott wrote in July of last year, “There is specific and compelling evidence that psychotropics are underutilized in treating dementia and it is time for C.M.S. to re-evaluate its regulations.” The statement goes on to advocate for the increased use of antipsychotic medications to treat “neuropsychiatric symptoms” of dementia such as wandering, aggression and sleep disturbances. It makes no mention of the risks.

And there’s no doubt that on one level, he’s right. Sedated patients are easier to care for. If one ignores the risks, keeping difficult patients quiet and compliant makes perfect sense. Staff are less stressed; other patients are happier; and visitors don’t complain. But how can the industry advocate for the practice when it so clearly shortens lives?

Conflicting priorities notwithstanding, nursing homes are on the front lines of the nation’s struggle to provide high quality, affordable, long-term care to our most vulnerable elderly. And as Mr. Blakeney’s terrible story demonstrates, we have to do a better job.

Antipsychotic Drugs Widely Prescribed in Nursing Homes

Antipsychotic Drugs Widely Prescribed in Nursing Homes

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

My 100 year old bed ridden Uncle was diagnosed with Geriatric Psychosis.

He has had many strokes and has dementia due to this. His Doctor who is also

Head of a nursing home facility prescribed Haldol . I was shocked !

No telling how many elderly patients are misdiagnosed to shit them up and prescribe

Antipsychotic drugs..

Report this comment

Hi Dale,

I’m sorry about your experience, but not surprised. Doctors and other care providers have become accustomed to using antipsychotic drugs in lieu of more appropriate interventions because they are a quick, easy and inexpensive “fix”. As long as CMS lets the practice continue, families must be the watchdogs and voices of those who can’t advocate for themselves.

Report this comment

My 100 year old bed ridden Uncle was diagnosed with Geriatric Psychosis.

He has had many strokes and has dementia due to this. His Doctor who is also

Head of a nursing home facility prescribed Haldol . I was shocked !

No telling how many elderly patients are misdiagnosed to shit them up and prescribe

Antipsychotic drugs..

Report this comment