A new report shines a light on how industrial sites are exposing Americans to cancer-causing pollutants at a much higher rate than the EPA considers acceptable.

The nonprofit newsroom ProPublica examined EPA reported data and found that a quarter of a million Americans are exposed to air pollution deemed to cause an “unacceptable risk” for developing cancer.

What Is an”Acceptable Risk” of Cancer?

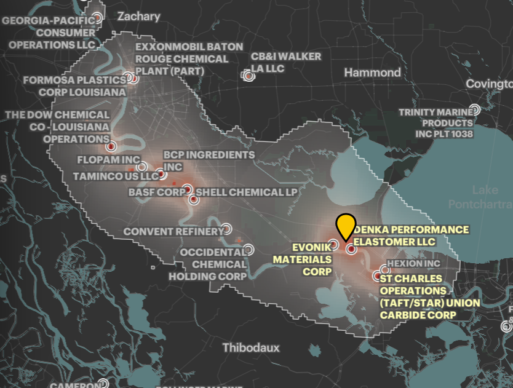

ProPublica mapped EPA data identify over 1,000 areas of increased cancer risk in the U.S.

Credit: ProPublica

Journalists examined data reported between 2014-2018. While always publicly available, the investigative nonprofit created a map of the data that starkly lays out the severity of exposure across the country.

The EPA’s definition of “acceptable risk” is 1 in 10,000. That means there would be one additional case of cancer in 10,000 people in an area exposed to polluted air over the course of a presumed lifetime of 70 years. However, that figure is the EPA’s upper limit of what’s acceptable. The environmental agency stated a much loftier goal to “protect the greatest number of people possible to a maximum individual risk level no higher than approximately one in one million” in a May 2021 report.

“The public is going to learn that EPA allows a hell of a lot of pollution to occur that the public does not think is occurring,” Wayne Davis, an environmental scientist formerly with the EPA told ProPublica.

Cancer is the second-leading cause of death in the United States behind heart disease. “Air-toxics” or hazardous air pollutants are linked to a laundry list of ailments, including lung cancers, breast cancers, and lymphomas.

The report found 256,000 people are being exposed to risks beyond the EPA threshold and that an estimated 43,000 people are being subjected to at least triple this level of risk. Meanwhile, the agency lacks the power to enforce its upper threshold. The law doesn’t require the EPA to penalize polluters that raise the cancer risk above the acceptable threshold, leaving the 1 in 10,000 figure more of a guideline.

Hot Zones

The map is littered with glowing red dots and masses. Zoom in on any crimson-colored square to uncover more disturbing information. In New Castle, Delaware, the British-based specialty chemical company Croda Inc. belches ethylene oxide, a toxic chemical linked to lymphoma and breast cancer, a mile away from children running around a daycare center’s playground. The area has a cancer-risk level of 1 in 2,200, or 4.4 times the EPA’s acceptable amount. In 2018, pollution from the chemical plant shut down the Delaware Memorial Bridge. In 2020 state regulators shut down the plant for months due to violating air pollution limits. The plant resumed operations in March 2021.

Policies of redlining and environmental racism places people of color at a higher risk of developing disease.

Credit: ProPublica

Environmental Racism Defines Polluted Areas

The risk zones’ sizes, severity and frequency are not distributed evenly by design. A quarter of the 20 hot spots with the highest levels of excess risk are in Texas, and almost all of them are in Southern states with weaker environmental regulations. Areas in which the majority of residents are people of color are subjected to 40% more carcinogenic industrial air pollution than areas where residents are mostly white. Predominantly Black areas in the study experienced more than double the risk of majority-white areas.

The infamous Cancer Alley crams a section of the Mississippi River in Louisiana with 150 oil refineries, plastics plants, and chemical plants. The toll on the residents is so great that the United Nations denounced the industrialization of the area as a form of environmental racism, a practice where governments and private industry target Black neighborhoods to build their plants or facilities and red-lined families out of safer areas, thus exacerbating poor health outcomes and economic conditions.

“Industries rely on having these sinks — these sacrifice zones — for polluting,” Ana Baptista, an environmental policy professor at The New School, told ProPublica. “We sacrifice these low-income, African American, Indigenous communities for the economic benefit of the region or state or country.”

ProPublica cautions that its map is not a tool for risk-assessment of cancer cases tied to certain areas to air pollution, but rather “a screening tool” for folks to see what is in the air they’re breathing and the dangers that accompany air toxics.

New Report Identifies Cancer Risk Hot Zones Around the Country

New Report Identifies Cancer Risk Hot Zones Around the Country

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition