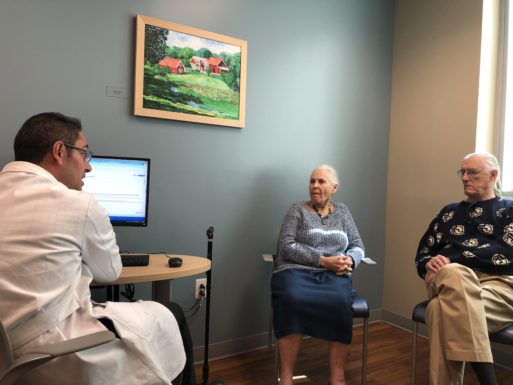

A Florida specialist expresses disbelief that Susanne Sherman, 87, is not on any medications.

As U.S. adults live longer, and with more chronic conditions, they are consuming increasingly large numbers of pills – a situation known as “polypharmacy.” But taking multiple medications can put patients at risk for adverse reactions – not to mention drain their wallet. They can also become confusing to track. But the worst part? Some of these pills may be doing the elderly more harm than good.

Polypharmacy is commonly defined as taking five or more medications. Multiple medications are a particular concern for older adults as a drug’s negative interactions with another medicine, with the patient, or with a disease may result in increased falls, frailty, disability and mortality.

Dr. Caleb Alexander

“A typical 75-year-old may have diabetes, hypertension, emphysema and osteoporosis — and that alone could require four to eight or ten medicines to treat,” said Dr. Caleb Alexander, a professor of Epidemiology and Medicine at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “Many elderly have not one or two conditions, but three, four, five that could be chronic, and potentially treatable with pharmacologic therapy.”

The problem of polypharmacy is multi-faceted: Many patients, caregivers, and doctors aren’t fully aware of its dangers. Even when they are, few know how to best address the problem. Writing to an advice column at The Oklahoman newspaper, one concerned daughter noted, “My 75-year-old mother is currently taking 16 different prescription and over-the-counter medications and I’m worried she’s taking way too many drugs. Can you suggest any resources that can help us?”

While the medical system is just beginning to explore ways to address polypharmacy, patients and caregivers can advocate for themselves by keeping medication lists, requesting a consultation with a doctor or pharmacist, and asking lots of questions. Meanwhile, experts are increasingly putting their minds together to assess what can be done about this growing problem on a systemic level.

The Rise of Polypharmacy

The number of Americans aged 65 and older skyrocketed to 55.8 million in 2020, or one in six people – the largest ever 10-year numeric gain and the fastest growth rate since 1880-1890, according to the U.S. Census. Many of those are dealing with multiple chronic conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension – resulting in unexamined polypharmacy.

In many cases, over-prescribing is influenced by a tendency toward specialization in the U.S. medical system. “Polypharmacy often extends from treating condition by condition, but not realizing that you sometimes need to pull back,” said Dr. Kenneth Covinsky, a Professor of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine and a clinician-researcher in the UCSF Division of Geriatrics. “The needs of people change over time, too – goals of care change, and quality of life issues change – so polypharmacy often comes from looking at everyone’s disease list and not looking at the whole person.”

While polypharmacy can affect individuals of any age group, statistics show that it is much more common among older adults, particularly among women. In a 2015-2016 survey, the National Center for Health Statistics found that of U.S. adults aged 40-79, nearly 70% used at least one prescription drug in the prior 30 days, while 22.4% met the standard definition of polypharmacy by taking five drugs or more. The incidence of both single prescriptions and polypharmacy increased significantly among older adults, however – affecting 83.6% and 34.5% of those aged 60-79, respectively. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 42% of adults aged 65 and older engaged in polypharmacy between 2015-2018, compared to 18% aged 45-64.

Often, doctors are shocked to encounter an elderly patient who is not on multiple prescriptions – such as 87-year old Susanne Sherman. When she and her husband met with a specialist at the University of Florida Health Shands Hospital in Gainesville, Florida, several years ago, the doctor took a look at her medical records and said “It says you take no medications – that can’t be correct.” Sherman assured her that it was.

Other times, multiple medications are necessary – prompting doctors and researchers to distinguish between “appropriate” and “inappropriate” polypharmacy. In 2017, the World Health Organization launched an initiative called Medication Without Harm as its third international Global Patient Safety Challenge in an effort to reduce inappropriate prescribing and the problems that result.

Dr. Kenneth Covinsky

Inappropriate medications become an issue when they’re hurting more than they’re helping. In his gerontology practice, Covinsky said the most common example he sees is with diabetes medicines, because “the benefits of really having very tight control of blood sugar in diabetes go down with age.” Studies have associated episodes of hypoglycemia with loss of cognitive function, potentially contributing to dementia. “One of my most common recommendations is to relax treatment of the diabetes – that more harm is being done than good by overtreatment of the blood sugar,” he said. Covinsky added that the guidelines for prescriptions are often not well adapted for older adults. He said that whether patients should take a new drug or not can depend on additional factors, such as a history of heart disease when considering cholesterol medication.

Dr. Michael Steinman, a geriatrician and professor of Medicine at the UCSF School of Medicine, said that because the side effects of medications are often nonspecific, such as stomachaches, dizziness or diarrhea, they can also be confused with indications of an illness. “That person and their doctor and their healthcare team might think those are symptoms of an underlying disease when in fact they can be side effects of medicines,” he said. “So we end up doing all kinds of diagnostic tests and maybe adding new medicines to treat that condition as opposed to recognizing that it was an adverse event of something the person’s already taken.”

Such unchecked approaches can place a tremendous burden on the healthcare system in addition to endangering the patient. “There’s an enormous amount of healthcare utilization, emergency departments and hospitalizations — and worse, death — that result from adverse drug reactions among the elderly in the United States,” Alexander said. “Some of these are unpredictable, but many of them are not, and many of them are logical consequences of the use of potentially risky combinations of medicines, or medicines that don’t make great sense overall in the risk-benefit balance.”

“Once patients have started a medication, they typically continue to take it – whether or not it continues to be needed,” Steinman said. Many doctors will refill prescriptions without fully understanding their history or long-term implications. “No one is really minding the ship, and paying close attention to it,” he said. “So there is this issue of overly prolonged treatment as well.”

How Seniors Can Address Polypharmacy

Advocates seeking to address the dangers of polypharmacy advise patients to engage with a primary care physician, family doctor or geriatrician who can oversee their care in a more holistic manner. “Once you have that person, sit down and make sure that they know all of the different medicines that you’re taking,” Steinman said. “And that can include prescription medications that you’ve got from any other source, as well as anything you might be buying over the counter, and herbal medicines or supplements you might be using.”

Dr. Michael Steinman

Dietary supplements commonly used by older adults include multivitamins and individual vitamins or minerals, as well as fish oil and other cardiovascular-oriented supplements. Over-the-counter drugs such as NSAIDS (Ibuprophen, Advil and Motrin) and sleep medicines are also widely used. “People think, ‘I can get them over the counter, they must be safe,’” Steinman said. “But particularly for older adults, they can actually have a lot of side effects. And for that reason, they can really end up causing a lot of harm.”

Steinman advised elderly patients and their caregivers to schedule a doctor’s visit specifically to go over all of their medications. He warned that it’s important not to mistake the initial intake done by a nurse or other healthcare worker for a medication review, as they are only seeking to establish a correct list and not to evaluate the necessity and quality of the drugs. “You need to explicitly ask the doctor that you’re seeing to talk about your medicines,” he said. The next step is then to ask a series of questions that will clarify what can be done to reduce the drug burden.

Covinsky said that phrasing questions in the right way can be important. “‘Is there a medicine I don’t need?’ may not be the right question,” he said. “You could often check some reason you’re on a medicine. But is there a medicine on my list where maybe the benefit is less than other medicines?”

It’s also important to ask questions that clarify the purpose and nature of new medications. Patients may want to establish a goal for new prescriptions with their healthcare provider, Covinsky said. “You might want to tell your doctor that your threshold for starting a new medicine is not just some likelihood, but that there’s a very compelling reason that you’re better off with it than without it…. Because even if you can list a benefit for each medicine, taking 10 medicines in aggregate is probably not a good thing.”

________________________________________________

Questions For a New Prescription:

• What am I taking this medication for?

• What is the evidence that this is going to help me?

• How should this medication help me feel better?

• What are some side effects that I might expect?

• How do I take this medicine?

• How long should I expect to be on this medicine?

• Are you concerned that this medication might interact

with any of my other medications?

• If I’m going to start a new medicine, is there another

medicine on my list that we could take off?

________________________________________________

In addition to doctors and nurse practitioners, pharmacists are a key resource for patients seeking to pare down their medication list. “Doctors aren’t always the most well-versed in medication interactions or even whether the dose of a medication needs to be adjusted to account for impaired kidney function or liver function,” said Tasha Woodall, a clinical pharmacist and co-director of the MAHEC Center for Healthy Aging in Asheville, North Carolina. “That’s when a pharmacist can be really helpful.”

Tasha Woodall speaks with a doctor at one of MAHEC’s geriatric primary care clinics

Woodall said patients can request a consult with the clinical pharmacist in their own health system. When one is not available, community pharmacists offer an alternative option. “I think most pharmacists would really welcome the opportunity to talk with people,” she said, adding that “it’s going to help the community pharmacist if the person can call ahead to request some time as opposed to dropping in during the busiest time of the day.” (The American Society of Consultant Pharmacists also lists pharmaceutical consultants by area, though these may not be covered by insurance.)

During a consult, Woodall emphasized that patients should bring a current medication list stating the name of each drug, the dose, and the reason they’re taking it – without that, it’s difficult for a pharmacist to know exactly what medicines a patient is on. She noted that patients will often use multiple pharmacies because they have different prescribers, or for reasons of cost. Then, there are the additional supplements and over-the-counter drugs. “You’re used to counting the number of pills in your hand, but think about the inhalers and breathing treatments, and the eyedrops, and the topical steroids,” she said. “It’s really important to get a complete list of all of those things as well.”

________________________________________________

Questions For a Current Medication List:

• Are each of these medicines still needed?

• Are there any side effects I should be watching out for?

• Can we make any changes to decrease these medicines

that might improve my health?

_________________________________________________

Experts note that a medication review is not a one-time thing, but something that should be engaged on a regular – perhaps, annual – basis. “There’s a good chance that there are some things that a person’s been taking for a condition that’s resolved long ago, and they don’t need that anymore. Or they’re at a point where the risk now outweighs the benefit. So having time set aside with their provider can be really helpful to talk through all of those things,” Woodall said.

The Movement to Deprescribe

Doctors have been educated to prescribe medicines, and are regularly encouraged to do so by pharmaceutical representatives. Even when non-drug treatments – such as physical therapy, lifestyle changes or dietary adjustments – could make more of a difference than medication, a prescription is simpler, and temporarily more satisfying. “It’s a very tangible act, and it’s easy to do, because it’s just putting an order into a computer,” Steinman said. “We need to resist that temptation, both as healthcare providers, but also as patients. Sometimes the quick fix of a pill is not the right answer.”

Dr. Thomas Radomski

Hospice providers may be more practiced than most in cutting back on medications for elderly patients. As patients’ healthcare goals shift from aggressive treatment to comfort care, the understanding that drugs may be hurting more than they’re helping becomes more accessible. Still, research suggests that those receiving palliative care, or long-term comfort care for chronic conditions, still suffer reduced quality of life due to polypharmacy. “When [a patient’s] death is truly imminent, and they’re in comfort measures-only phase where they might have only hours or days left, lots of medications will typically be discontinued,” said Dr. Thomas Radomski, an internist and assistant professor of medical and clinical and translational science at the University of Pittsburgh. “But for those patients who are in the four-to-six months time frame in terms of their life expectancy, there’s less of a push to discontinue a lot of their chronic medications.”

In recent years, there has been an emerging movement to deprescribe – particularly for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. The American Medical Association established a policy to reduce polypharmacy as a significant contributor to senior morbidity. And the National Institute on Aging has funded a U.S. Deprescribing Research Network, which brings different healthcare professionals together to engage in interdisciplinary research, including geriatricians, surgeons, cardiologists, pharmacists, healthcare administrators and patients.

“This is a complex problem, it’s not the domain of any one single specialty or any one single profession,” said Steinman, who is also the network’s co-director. “It involves everyone, so we need to think about engaging these different types of expertise and different kinds of perspectives as people work through the healthcare system and through their lives and make sure we’re hitting all the right points.”

Additionally, researchers including Radomski are developing a metric, called EVOLV-Rx, that could be used to flag patients in the electronic medical record who are at risk for low-value prescriptions, prompting a clinical pharmacist to follow up with both patients and their doctors about reducing their medication burden.

Regardless, the nascent movement toward deprescribing faces monumental challenges. The U.S. is experiencing a widespread shortage of primary care physicians and geriatricians. There is still only minimal systemic support for the initiative, and patients can be fearful of cutting back on medications even when a doctor recommends that they do so. Sometimes, patients are encouraged by direct-to-consumer advertising to seek out medications or supplements they might do best without. “While they may or may not be asking for a specific medication, it’s not uncommon that if someone sees advertising, they might get the conversation started about just prescribing something, or trying something, for that condition,” Radomski said.

For now, experts say, patients and caregivers can best serve their own health by educating themselves about polypharmacy and advocating that their providers pare down medications when appropriate. “Part of it is education and part of it is culture change, and part of it is changing the system that makes getting these non-pharmacological treatments easier,” Steinman said. “It’s setting the system to make it easier to obtain those sorts of interventions, and also reframing people’s expectations so they’re not expecting a pill as the right thing to do. And that’s a big lift – it’s not going to happen overnight.”

Exploring the Drug Problem No One Talks About: Overprescribing to the Elderly

Exploring the Drug Problem No One Talks About: Overprescribing to the Elderly

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”