It has been over 35 years since the medical community first became aware of a strange and deadly disease that mainly affected gay men. The news first broke in June 1981, when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a report describing an unexplained outbreak of a rare form of pneumonia, pneumocystis carinii, in five previously healthy young gay men. Within days, the agency was flooded with reports from doctors across the country, all describing gay men with similar infections. Some also had a rare form of skin cancer known as Kaposi’s sarcoma. All of the men showed signs of severe immunodeficiency.

By the end of that year, doctors had identified 270 cases of the unexplained illness, and 121 of the patients had died.

And so the AIDS epidemic began.

Jermerious Butler lives in Jackson Mississippi. He has had AIDS since 2008

Credit: Arkie Tadesse/tonic.vice.com

Uneven Progress

Since those horrifying early years, the United States has made enormous strides in the prevention and treatment of HIV and AIDS. Once the leading cause of death in men and women between the ages of 25 and 34, AIDS is now No. 8. And since 2006, both the number of new cases of HIV and the number of people dying from AIDS has fallen steadily.

And all of that is great news.

Credit: CDC.gov

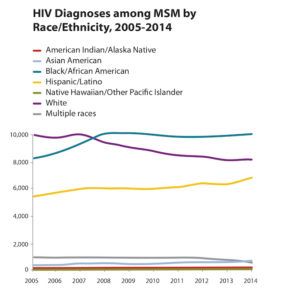

Unfortunately, however, the story doesn’t end there. Recent data from the CDC shows that, in parts of rural America, the rate of HIV infection in men who sleep with men is increasing at an astonishing rate. According to Mother Jones, new cases of HIV in gay and bisexual men of color between the ages of 13 and 24 has increased by 87 percent since 2005. And over 60 percent of these transmissions come from men who know they are infected but are not receiving care.

The problem is most acute in the Deep South, where poverty and lack of access to healthcare translate to a rate of HIV infections that far surpasses the country as a whole. In Jackson, Mississippi, for example, HIV prevalence in gay and bisexual men of color is around 40 percent, reports the N.Y. Times. That’s 12 percent higher than the rate of infection in Swaziland — a tiny African nation that has the highest prevalence of HIV in the world.

Prevention Is Possible

These numbers are particularly tragic because the tools to prevent most HIV transmissions already exist. One is the “test and treat” strategy the CDC has recommended since 2012, which encourages healthcare providers to prescribe antiretroviral therapy as soon as a person tests positive for the disease. The second is pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP for short) with the drug Truvada. According to two large clinical trials, when uninfected people take Truvada daily as directed, it’s 99 percent effective in preventing transmission of the disease.

HIV testing is best used in conjunction with early treatment and prevention

Credit: antiaids.org

But availability doesn’t mean access. And in the inner cities of the Deep South, fewer than 50 percent of men who know they have HIV take medication consistently, and that number is lower in teens. In fact, about 20 percent of gay and bisexual black men only learn they have the virus when they develop symptoms of AIDS. And a shocking number of those men — nearly 3,000 in 2014 — die from their disease.

In 2015, then CDC director Thomas Frieden wrote about the growing HIV crisis in an essay published jointly with Jonathan Mermin, the director of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. The two warned that “hundreds of thousands” of Americans are still becoming infected with HIV every year, and called for better outreach and education in high-risk communities.

“We need to boldly address stigma, discrimination, and other social, economic, and structural issues that increase vulnerability to HIV and come between people and the care they need,” they wrote.

But with a new CDC director and a new administration in Washington, it’s unclear whether those priorities still hold true today. For the sake of the many thousands of people whose lives depend on a strong response to this growing crisis, let’s hope they do.

HIV: The Epidemic We Haven’t Stopped

HIV: The Epidemic We Haven’t Stopped

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition