Remains believed to be from Delisha and Tree Africa, two victims of the 1985 MOVE bombing, are missing.

Credit: Visit Philly

Over 35 years after the Philadelphia police department dropped a bomb on its own citizens, the whereabouts of the remains of two victims is unknown. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology had been the home of the remains for decades. But local news outlet Billy Penn reported on April 22, 2021, that despite Penn’s assertions that the remains were moved to a facility at Princeton University, Princeton officials could not locate the bones that are believed to belong to two children killed in the tragic 1985 bombing that burned down two city blocks and claimed 11 lives.

Critics say the mishandling of the remains is just another example of the pattern of dehumanization by Philadelphia’s esteemed institutions of its Black residents. It also calls into question the ethically dubious practice of keeping human remains in museums. Student and activist groups are calling for the bones to be returned and the Penn Museum to pay reparations for holding onto the bones for so long.

“They were bombed and burned alive and now you wanna keep their bones,” Mike Africa Jr., son of MOVE members Mike Africa and Janine Africa, told Billy Penn.

Aftermath of the 1985 MOVE bombing on the 6200 block of Osage Ave

and Pine Street

Credit: collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu

MOVE and Philadelphia: A Decades-Long Clash

The mistreatment of the remains would be an injustice in itself, but Philadelphia’s fraught history with the MOVE organization adds to the larger tragedy these remains are a part of.

MOVE is a black liberation movement committed to working against injustice and promoting environmental causes. It was founded by John Africa, formerly Vincent Leaphart, in West Philadelphia in the early 1970s.

“We demonstrated against puppy mills, zoos, circuses, any form of enslavement of animals. We demonstrated against Three Mile Island and industrial pollution. We demonstrated against police brutality. And we did so uncompromisingly. Slavery never ended, it was just disguised,” MOVE member Janine Africa told the Guardian in 2018.

While their causes were many, their unorthodox methods of profane bullhorn-amplified rants and keeping stray dogs brought them into disputes with neighbors. These came to a head in 1978 when a court-ordered eviction turned into a shootout with the Philadelphia police, resulting in the death of one officer, James Ramp. Nine adult MOVE members were arrested, charged and eventually convicted and sentenced to 30 years to life for Ramp’s death. A judge would dismiss the charges against three officers under investigation for police brutality during the clash.

Seven years later, the relationship between MOVE and Philadelphia took a darker turn. After obtaining warrants for four MOVE members, 500 police officers surrounded the new MOVE residence at 6221 Osage Avenue on the morning of May 13, 1985. MOVE did not answer the police’s initial requests to exit the building, and a siege that would turn deadly began on the block. Philadelphia PD ordered neighbors out of their homes with the promise they could return in 24 hours. The ensuing standoff, featuring a deluge of water cannons, tear gas and a 90-minute gunfight in which police spent over 10,000 rounds of ammunition, left the city desperate. Focusing on a fortified bunker at the top of the house, Mayor Goode signed off on the use of two one-pound bombs, packed with Tovex — a dynamite substitute — supplied by the FBI.

The fire from the explosion quickly overtook the MOVE residence and later the neighboring homes. MOVE members say they were trapped between a burning building and gunfire from police while they tried to escape. The blaze raged on with firefighters on standby with orders to wait until the bunker fell. By the time they intervened, it was out of control. The fire razed a block of Osage Avenue and nearby Pine Street, destroying 65 homes in total. Only two MOVE members would survive, Ramona Africa and a 13-year-old boy. Eleven people died, including five children and founder John Africa. A special commission was formed to investigate the bombing, and a report issued a year later denounced the city’s actions, stating that “dropping a bomb on an occupied row house was unconscionable.”

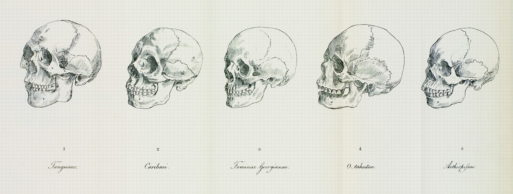

Samuel Morton helped popularize the racist and white-supremacist belief of craniology, that head shape dictated intelligence and behavior.

Credit: Penn Museum

A Pattern of Dehumanization

During the MOVE Commission’s investigation, the city medical examiner’s office gave the remains in question — a pelvic bone and a femur — to Penn anthropology professor Alan Mann to verify the initial expert claims that they belonged to Tree Africa, 14, and Delisha Africa, 12. Mann and his team refuted the initial claim, stating that their results showed the remains belonged to a person around 18 years or older, adding the chilling prospect of a 12th and to-date unidentified victim. This led the MOVE commission to determine the findings “inconclusive,” although many still believe the remains to belong to Tree and Delisha.

City policy requires that after analysis, remains are to be returned to the next of kin or else cremated if they are unidentifiable and no one claims them. But the bones stayed in the possession of Mann even when he moved to Princeton in 2001, Billy Penn reported. The bones were sent back to Penn and Janet Monge, curator of Penn Museum’s physical anthropology section, from 2016 to 2019 for reanalysis. Monge had actually encountered the bones before, assisting Mann in his work to identify them in 1985.

The bones also appeared in a 2019 Coursera video released by Penn in which Monge and a graduate student poke and prod the bones while discussing the age of the victims impersonally. In the video, Monge again asserts that the bones were not from the child victims of the MOVE bombing.

Carolyn Rouse, chair of Princeton’s anthropology department, responded to the Philadelphia Inquirer’s questions about the use of the bones in the teaching exercise, stating, “The remains were used as an instructional aid to teach a discipline with ramifications for history, epidemiology and archeology, among others.”

The stewardship of the bones remains up in the air as Penn claims they were transferred back to Mann at Princeton in 2016, despite Mann’s move to emeritus status in 2015. After the story broke, Princeton conducted an internal investigation and found that “no remains of the victims of the MOVE bombing are being housed at Princeton University,” according to Billy Penn.

A Continued Controversy

This instance is not the first time the Penn Museum has faced controversy over its physical anthropology collection. In July 2020, in response to years of student and community protest, the museum promised to repatriate over 1,000 skulls it had received from the collection of Samuel Morton. Morton was a prominent 19th-century Penn researcher and white supremacist, and many of the skulls in the collection were retrieved from graveyards and battlefields. The collection included the skulls of at least two people who were enslaved in the United States and 53 enslaved people in Havana, Cuba, according to the Penn and Slavery Project.

Penn’s promise is part of a growing movement for institutions to decolonize their collections and rethink the ethics of keeping remains of Black people and people of color taken without the consent of their families.

Critics have said collections featuring the likes of stolen skulls or bones from the MOVE bombing continue to dehumanize the people they belonged to and disregard the wishes of the generations of kin that came after.

“Many of the remains of Black people, like those of Native Americans, were taken without the consent of the family, used in ways that contravened spiritual traditions, and treated with less respect than most others in society,” wrote Delande Justinvil and Chip Colwell in an opinion piece for The Conversation.

Black bodies, such as Henrietta Lacks or those in the Tuskegee syphilis experiments, have been the foundation on which science and anthropology have advanced. The casual mistreatment or even indifference in how they are treated, whether alive or dead, perpetuates the same inhumanity and injustice seen every day the world over. If institutions fail to respect the dead, how can we expect them to hold much respect for the living?

Remains of Child Victims in MOVE Bombing Unaccounted for by Penn Museum, Princeton

Remains of Child Victims in MOVE Bombing Unaccounted for by Penn Museum, Princeton

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!