Rodents carrying infected fleas spread the Black Death across Europe and Asia.

Credit: Brendan Christopher

From 1346 to 1353 the bubonic plague swept Europe and Asia, killing between 25 and 50 million people. It was one of several strains of plague caused by Yersinia pestis, a bacterium spread by rodents carrying infected fleas. The scourge became known as the Black Death due to the black, gangrenous sores it caused in the tissues of its victims, in addition to fever and swollen, pus-leaking lymph nodes.

Scientists have been unclear about how Y. pestis evolved into the Black Death strain, one of several that developed when the bacterium diversified and that still occurs today. While still deadly, the plague can now be treated early on with antibiotics. But the first effective treatment, antiserum, wasn’t discovered until 1896, some 500 years after the Black Death took hold.

Now, new research published in the journal Nature has confirmed that DNA obtained from two cemeteries in modern-day Kyrgyzstan shows the presence of Y. pestis. Human remains in the graveyards were long suspected of belonging to early plague victims, as dates inscribed on their tombstones indicated that many were buried eight years before the Black Death began. Researchers examined tooth samples and found evidence of Y. pestis DNA. They were then able to compare the DNA samples to earlier and later plague strains and determine that they predated the one causing the Black Death.

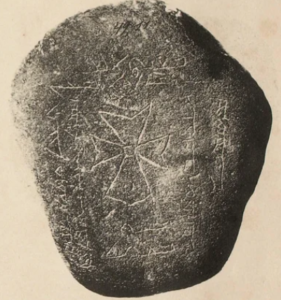

A tombstone from the graveyard in Kyrgyzstan reads, in part: “This is the tomb of the believer Sanmaq. He died of pestilence.”

Credit: A.S. Leybin, 1886

Evolutionary geneticist Hendrik Poinar, who serves as director of the McMaster University Ancient DNA Center in Ontario, Canada, and was not involved in the study, told NPR that the discovery doesn’t necessarily mean the mystery of the Black Death’s origins has been entirely solved. “Pinpointing a date and a specific site for emergence is a nebulous thing to do,” he said, explaining that the bacterium evolves slowly, and could have been carried from elsewhere by traders. Nevertheless, he added, it provides an important piece of the puzzle.

Maria Spyrou, lead author of the study and a researcher at the University of Tübingen in Germany, emphasized that the information is one part of a much larger picture. “Our current abilities in making precise connections between the past and the present are critical in understanding how infectious diseases emerge, which types of hosts are involved in their emergence, how they disseminate among human populations, and what factors have determined their present-day distribution and diversity,” she told Medical News Today.

Mystery Solved? Origins of the Black Death Explored

Mystery Solved? Origins of the Black Death Explored

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One