“Code blue.” These words, transmitted over a hospital’s loudspeaker, announce a life-threatening cardiac or respiratory arrest – resulting in trauma for the patient, as well as doctors, nurses and other hospital staff. When a code blue is called, anywhere from 15 to 50 professionals – including physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, residents and transporters – rally to save a patient’s life. Many times, despite their best efforts, they fail.

“Code blue.” These words, transmitted over a hospital’s loudspeaker, announce a life-threatening cardiac or respiratory arrest – resulting in trauma for the patient, as well as doctors, nurses and other hospital staff. When a code blue is called, anywhere from 15 to 50 professionals – including physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, residents and transporters – rally to save a patient’s life. Many times, despite their best efforts, they fail.

While a code blue death is more traumatic than most, losing a patient is never easy – and contributes to the immense levels of stress and burnout documented among medical staff. Forty-four percent of physicians report feeling burned out, according to Medscape’s 2019 National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report. An estimated 400 physicians commit suicide in the U.S. every year, while a recent study from the University of San Diego found that nurses have a significantly higher suicide rate than the general population. As many as 28 percent of nurses experience post-traumatic stress disorder over the course of their careers.

Increasingly, doctors and nurses are embracing innovative ways to cope with the trauma that comes from handling code blues and other patient deaths. Perhaps surprisingly, many of these efforts involve finding greater connection with patients who are dying. By recognizing and honoring the humanity of those they serve, hospital care providers find that they are able to mitigate their own feelings of distress about the suffering they’re forced to witness daily.

Code Blue: Traumatic Life-Saving Effort Rarely Succeeds

Popular television programs including “ER” and “Grey’s Anatomy” portray doctors and nurses as heroic figures who, rushing into a code blue, save the majority of their patients’ lives. In reality, these numbers are much more bleak. Of the more than 290,000 adults who suffer cardiac arrest in U.S. hospitals each year, only about 25 percent survive. Of those, less than half live to leave the hospital.

Marilyn Reiss-Carradero, RN, BSN

The fact that a code blue is rarely effective is made even more traumatic by the violent nature of its performance. Marilyn Reiss-Carradero, a rapid response nurse at a busy urban hospital in California, is involved in as many as a dozen of the roughly 100 code blues the facility handles every year. “If CPR is done right, it breaks your ribs and your sternum,” she said. “That is just a fact. So if you are consenting to CPR you are consenting to us punching you so hard that we break your ribs.”

Doctors and nurses will work simultaneously to obtain IV access through a patient’s legs and arms, while others insert a breathing tube down the patient’s throat or administer shocks from a defibrillator to restart the heart. “When you shock a patient they literally jump – their body jumps,” Reiss-Carradero said. “The first time you see that, that’s an image you just don’t forget.” While a shock is typically administered from one to 15 times, Reiss-Carradero once participated in an exceptionally traumatic code blue in which the patient was shocked 52 times. “Especially when you’re working on somebody that is elderly, truly we feel like we are torturing or contributing to a very violent death,” she said.

Reiss-Carradero is hardly alone in this sentiment. Dr. Jessica Nutik Zitter, a pulmonary critical care and palliative care-trained physician at Oakland’s Highland Hospital, regularly experiences the trauma of code blues and acknowledges that it’s not always easy to manage the emotions involved in efforts to prolong life in those suffering from terminal illness. “To witness, and frankly even know that you’re contributing to, suffering in a person, you don’t feel the compassion because you avoid it,” she said. “You move away from it – it’s too painful to witness, particularly if you feel you’ve played a role in it. And so you withdraw further, and that’s extremely distressing and numbing. Numbing is a way of managing it and surviving it. “

Samuel Slavin, a medical student at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston who interviewed a range of staff for a Transom radio piece called “Anatomy of a Code Blue,” found that all were deeply affected by the trauma of code blues, no matter what their role. During the event, equipment is tossed about, there is frequently a great deal of blood, and once a patient is pronounced dead, hospital staff will typically throw their gloves on the floor and leave the room.

A hospital room after a code blue

Credit: @traumacam

As Marie, a long-term member of the housekeeping staff told Slavin: “After a code I could compare it to, if you’ve seen a tornado, afterwards everything is strewn and everything is smashed.” She added, “You find some rooms that don’t have much on the floor – it makes me think, maybe that person survived? What am I thinking? I’m thinking, God – let this person live.”

New Programs Reduce Trauma of Code Blues

Roughly a decade ago, Jonathan Bartels was working as a trauma nurse in the University of Virginia Health System when he was inspired by a chaplain who asked everyone to stop after a patient’s death and said a prayer. While Bartels didn’t relate to the religious nature of her prayer, he was struck by the power of the concept, and translated it into “The Pause,” which uses secular language to call for a moment of silence. “You can have someone who’s Christian next to someone who’s Hindu next to someone who’s Buddhist, and someone who’s atheist or agnostic, all honoring that patient but doing it in silence,” he said. “But all with the same mission – which is really to take a moment to recognize this last rite of passage. To reinstate ritual, or a ritual, back into a system that has driven ritual out through its scientific pursuits.”

Jonathan Bartels, RN

Credit: Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare

Bartels said that he witnessed an immediate difference when experiencing the trauma of code blues and other patient deaths. “I didn’t just separate, I was able to close the gap from one act to another, and I was able to put [the trauma] down,” he said. “And then my peers were able to put it down. But it’s not – and I say this often – it’s not a panacea, it’s not a cure-all. This is the first step in many, many steps of what is really being called for to take care of ourselves.”

Since then, Bartels said that hospital professionals from New Mexico, Cleveland, Washington state – even as far away as South Africa – have reached out for advice in implementing similar practices. Reiss-Carradero was motivated to introduce a “Moment of Silence” at her hospital, during which staff recognize the patient by name, after reading about it in a journal article. “Just acknowledging that this is a sacred moment for that patient,” she said. “Because that’s what’s lost in a code blue death – there is nothing spiritual, there’s nothing comforting, there’s nothing calm and quiet.” Reiss-Carradero also began to take additional, personal steps, like covering the patient. “Now, I make sure that I touch them in some way,” she said. “Whether that’s holding their hand – it depends where I am in the room, if it’s crowded – or I touch their forehead.”

Honor Walks Recognize Generosity of Organ Donors

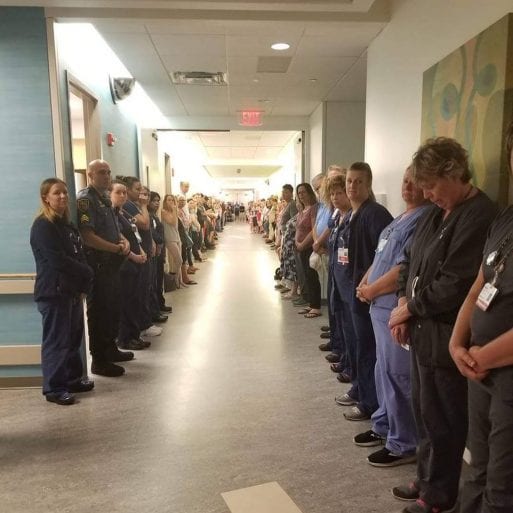

Other hospitals have begun similar efforts to recognize organ donors, known as “Honor Walks,” in which doctors, nurses and other hospital staff line the hallway as a recently deceased patient is wheeled into the operating room. Missy Holliday, Organ Operations Director at LifeCenter Organ Donor Network in Cincinnati, said she began implementing the practice at the 35 Cincinnati-area hospitals she works with in December of 2017 after a survey indicated that staff wanted to be more involved. “Our main priority is the donor and their family, but the idea spawned from hospital staff,” Holliday said. “Finding a way for hospital staff to feel connected to this really meaningful process.”

Holliday said that while it is voluntary, most families opt to have their loved one recognized by an Honor Walk. Anywhere from four to 100 friends and family members can show up for the event, which occurs at various times of day or night – whenever the patient is scheduled into the operating room. “When you see that whole line on both sides, with 50-200 people, sometimes more than that – people they don’t even know, people that have come out to pay respect to their loved one,” she said, “it’s overwhelming in a really positive way. And that’s the feedback we’ve gotten from hospitals – they feel that it is purposeful, and it is meaningful, and we should be doing it.”

In the past two years, Holliday has assisted numerous hospitals and organ donation agencies to institute the practice. When LifeCenter posted a photograph taken by family members of one donor, Cletus Schnieders, to Facebook, it went viral – inspiring still others, including Jennifer DeMaroney, Organ Donation Coordinator at the University of Vermont Medical Center. “It’s so striking,” said DeMaroney, who has since consulted with an estimated 100 hospitals on the practice herself. “I knew that at our hospital, this would be something that they would get really excited about.”

The viral photograph of Cletus Schnieders’ Honor Walk.

Credit: Carrie Schnieders

DeMaroney was right. Her hospital instituted Honor Walks just over a year ago, and has since encouraged families to personalize the experience. Many tape photographs of their loved one to the bed – often picturing them doing activities they enjoyed, such as hunting or fishing. One family held a Native American drumming ceremony, while another brought in their entire church gospel choir to sing throughout the process. For one elementary-aged girl, most of her class showed up to participate. “It’s bringing awareness, but it is also supporting the staff that are taking care of the donor and their family, because these cases are hard on everyone,” DeMaroney said. “People will tell you where they were when they saw their first honor walk, how it affected them.”

Such moments are powerful. Nutik Zitter vividly recalls the first time she witnessed an ER resident implement a moment of silence following a patient’s death. It was just a couple of years ago – something the resident had been taught in her training. “I was blown away, Nutik Zitter said. “I was so touched, and moved, and I thought, why haven’t we done this before? This is exactly what we need to do when a person’s life passes through your hands.” Since then, Nutik Zitter has continued the practice. “This is very big stuff, and it should be meaningful,” she said. “The second we stop seeing it as meaningful and human and poignant and sad and connecting, that’s when we start to lose our humanity.”

Palliative Care Encourages Compassion, Limits Code Blue Trauma

Doctors, nurses and other medical professionals are increasingly coming to an understanding of the importance of maintaining compassion – both on an institutional and a personal level. The reach of palliative care has expanded considerably in the past two decades, with palliative care teams present in 72 percent of U.S. hospitals with 50 beds or more – up from 7 percent in 2001. This growth demonstrates a developing understanding of the need to maintain compassion for patients, to clearly communicate needs and desires around end of life, and to work together as a community to address the needs of the dying. Some studies have even suggested that empathy can help physicians protect against burnout.

Compassion for patients often includes having difficult discussions around end-of life goals and code status – including whether the patient wants a full code or a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR). “It’s really important for everyone to have an advance directive,” said Bartels, the former trauma nurse who now works as a palliative care liaison, “because when you don’t have a voice, you need to find a way to have the voice for you. And an advance directive allows you to speak when you can’t speak. It allows you to let your family know – this is an acceptable point of living; this is not an acceptable point of living.”

Jonathan Bartels, RN, holds a patient’s hand

Credit: Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare

Dr. Karl Steinberg, who is medical director at Hospice by the Sea in Solana Beach, California, as well as at multiple nursing homes, advises that everyone 18 years or older have an advance directive, and that it can change over time depending on circumstances. “I witness every day the disasters that happen when you don’t,” he said. “The most important thing about an advance directive is to name the person that you want to be in charge. And make sure that person that can make the hard decisions and will be able to advocate for you – that they’ve got the personality to do that.”

While the level of honesty required for these conversations can be difficult, it is also becoming increasingly common. Dr. Sunita Puri, a palliative care physician and author of “That Good Night,” wrote of her training: “A goals discussion could be helpful only if the doctor could tell the patient, clearly and compassionately, if they were at a juncture where either of two trails would lead them to their destination, or whether they now found themselves unexpectedly at the edge of a cliff, their destination now out of reach.” For patients approaching that cliff’s edge, a different kind of discussion is required – not which treatments might save their lives, but which will make their deaths more comfortable.

The majority of doctors and nurses would not want many of the treatments they are expected to recommend for their patients – CPR included. But as more medical professionals learn to speak their mind about what they feel is best for patients approaching the end of life, they also learn to minimize their own distress. “What I would recommend to any of my family members is that you would allow somebody to do a full code on you if you were less than age 70, and having a heart attack,” Reiss-Carradero said. “The whole full code, CPR, when you have end-stage cancer, when you have renal disease, when you have congestive heart failure, when you have all of these other chronic conditions – CPR was never meant for that,” she said.

Palliative care teams benefit both patients and providers by bringing together a variety of specialties and areas of expertise to create a collaborative team. “A really good palliative care team, and team members, is going to make you realize that this team isn’t really led, or shouldn’t be led, by any one professional,” Nutik Zitter said. “The more I’ve learned that, the more my distress has melted away.” Such collaboration also allows practitioners to develop the depth of trust necessary to hold difficult conversations with patients. “We learn how to connect with people in ways that we didn’t learn in typical medical school classes,” Nutik Zitter said. “Working with chaplains and social workers who already learn this in a different way, in their education, we in the palliative care movement tend to be better and less agenda-driven at sort of forging an interaction and connection with somebody than is typical.”

Dr. Jessica Nutik Zitter, MD with a patient

Credit: Rikki Ward Photography

This collaboration increases support for the medical team as well. Dr. Lara Bickford, an ER physician at Kaiser Permanente in Portland, Oregon, says that the palliative care team at her hospital, consisting of physicians, nurses and social workers, has lessened her stress considerably. “They told us that they’re basically there to help us with whatever we need,” said Bickford, who will often call in the palliative care team to have goals of care conversations or manage chronically ill patients. “Lots of times it’s symptoms management with patients who are dying of cancer and other chronic diseases. They’re much more comfortable with large-dose narcotics and managing symptoms like air hunger, and really try to get the patient as comfortable as possible. I feel really lucky to have those resources – I know a lot of places don’t.”

Joe Perez, vice president of Mission and Ministry at Valley Baptist Health, who has spent many years as a chaplain in hospice, outpatient and inpatient settings, said he always makes an effort to include doctors and nurses when praying for a patient – whether that is going into surgery or following a patient’s death. “I allude to the idea of a journey,” said Perez, who oversees chaplain services at two hospitals in Harlingen and Brownsville, Texas, including around 18 staff and 40 volunteers. “We’re all walking this path together. And I think it’s something that breeds a sense of wholeness and health. It fights the idea of isolation and being alone, of course, and it also recognizes that not one person can do everything. That it takes a community of people to do this well.”

Perez said he will often follow up with doctors and nurses following a code blue – to check on them, affirm their effort, and acknowledge the difficulty of what they’ve gone through. “Especially if it’s a really hard one – a young person or something like that,” he said. “This is very hard work.” Palliative care doctors and nurses report that they will often do the same – either informally, or during a more formal debriefing.

Steinberg said that after a code blue takes place at one of the nursing homes he works for, or a patient dies from illness, staff will have some type of small ceremony to honor their passing. Sometimes nurses will anoint the body or provide aromatherapy, he said. “We try to do inservices, and we do some sort of grief work,” he said. “Nurses stand up at monthly meetings to acknowledge those who’ve died, and say a few words about the people they’ve cared for.”

More Resources Needed to Support Medical Care Providers

Still, many doctors and nurses find it’s not enough. When asked if there are enough resources available to medical professionals to deal with the trauma of patient deaths, Nutik Zitter said, “the answer is a resounding ‘No.’” In her recent book, Extreme Measures, Nutik Zitter discusses the lack of formal, frequent opportunities for doctors, nurses and others to process difficult emotions. “I think every hospital should have monthly Schwartz Rounds to process a case where you’re not looking at it from a medical physiology perspective, but you’re looking at it from the perspective of a human being and your experience in that case, how it felt emotionally,” she said. The Schwartz Rounds program, created by The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare and used by hundreds of organizations in the U.S. and beyond, offers healthcare providers regularly scheduled opportunities to discuss social and emotional issues. Those who participate often report decreased feelings of stress and isolation, improved teamwork and greater feelings of compassion toward patients.

Dr. Jessica Nutik Zitter, MD

Credit: Rikki Ward Photography

Some hospitals have begun initiating other programs that lean in this direction. Reiss-Carradero said that her hospital sends oncology nurses to a two-day end-of-life nursing class, but while other nurses have the option to attend, they lack the staff necessary to make it widely available. Bartels is part of the Compassionate Care Initiative at the University of Virginia School of Nursing and facilitates compassion resiliency retreats for nursing students, physician colleagues and staff nurses. “That uses a lot of different approaches, including laughter, joy, play, meditation, bodywork, journaling,” he said. “There’s not just one thing that we can do for ourselves. It’s really realizing that there are certain things that feed you, and it’s important to feed that part of yourself while you’re doing the intense work.”

Some physicians have developed their own personal practices. Dr. Louis Profeta, an emergency room physician practicing in Indianapolis, wrote a LinkedIn post that went viral about checking his patients’ Facebook posts after they died – and before he approached their parents to give them the news. While Profeta finds the practice “helps you recapture your humanity a little bit,” he said he wrote the article not to address how physicians can assuage their grief, but rather, to provide a framework for parents to discuss the consequences of reckless behavior with their children. “That was the whole idea – to give parents the words to tell their kids that this is what love looks like,” he said.

Profeta, who has been working as an ER physician for 25 years, said that he deals with fewer code blues these days because protocol has changed so that paramedics are more often calling deaths in the field. Still, he experiences a death roughly every third shift he works. While Profeta considers having to tell people about the death of their loved ones “the worst thing in the world,” he also finds it to be part of the job. “I feel the sense of loss,” he said. “But man, I come home from a busy day and I’ve comforted some people, I’ve helped people feel better, and saved some people’s lives. The key is to focus on that.”

Profeta, whose article “I Know You Love Me – Now Let Me Die” also touched thousands of readers, said that helping people have the conversations necessary to avoid a code blue can be difficult – particularly when doctors are immersed in bureaucratic demands that involve mounds of paperwork. “Doctors have to have the strength of conviction and courage to be able to do it,” he said. “You’re able to talk them out of it, and just let them go peacefully. It’s one of the most gratifying parts of my job.” And when it comes to stress? “Make sure that you know it’s just a job, and that you have a good home life,” Profeta advised. “That you pay attention to your family and your free time is valuable to you. And guess what? You’ll be more connected and more engaged at work.”

Hospital staff in a Schwartz Rounds Program to help them process

experiences with patient deaths such as code blues

Credit: The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare

For others, it often comes down to finding ways to embrace and process the sadness. “I’ve learned so much from the dying,” said Perez, who is also President of the Association of Professional Chaplains. “To learn how to carry sadness is really important – grief is a part of that, and mourning is part of that. Sadness deepens our heart. It helps us to go to deep places in our heart, and when we run away from sadness we actually stop ourselves from growing. We have to learn that sadness is actually the flip side of happiness or joy. And if we don’t go deep with the sadness, we can’t go deep with the happiness, either.”

One method that Reiss-Carradero used to address her own sadness was to write a poem. Beginning five years ago, she worked with some hospital chaplains to create an annual Day of Remembrance service, where she first read the poem, titled “Sacred Moments at the Bedside.”

“What do we do with all of these Sacred Moments?” it reads. “We grieve, we debrief, we try to let go, but these moments shake us and shape us. They guide us to appreciate the love and life we have now and to embrace death as the ultimate sacred passage…. Until the next moment comes.”

New Rituals Lessen Trauma of Code Blue Deaths for Clinicians

New Rituals Lessen Trauma of Code Blue Deaths for Clinicians

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition