SevenPonds hosted get-togethers with several groups of friends to play these nine

end-of-life conversation starter games.

Here in the United States and throughout most of the Western world, conversations about death are still pretty much taboo. We are a youth-obsessed culture that pours enormous amounts of time, energy and money into denying the realities of aging and infirmity. Every year, Americans spend about $16 billion on cosmetic plastic surgery and billions more on “anti-aging” products like hair growth potions and skin creams, all in the pursuit of the myth of eternal youth. Meanwhile, deaths from chronic illnesses like cancer, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease continue to soar. It’s as if our culture shares the collective delusion that disguising the truth will insulate us from what we fear most.

But, as it turns out, the exact opposite is true. Not talking about death, and more specifically about what we want at the end of our lives, sets us (and everyone who loves us) up to become victims of a system that will almost certainly ensure that our deaths are longer, more painful, and more financially devastating than they need to be.

And that’s why a small, dedicated group of entrepreneurs — some of them scientists, some of them physicians, some of them designers, some of them just ordinary people who want to change the way we think about end of life — has been working for years to create engaging and approachable ways to get us talking about death. From Ellen Goodman’s The Conversation Project, which provides free tools and advice to anyone who’s interested in opening up a conversation about their end of life wishes, to Death Over Dinner, an interactive website that has been helping people all over the world come together for a night of food and conversation about one of life’s most difficult subjects, the past two decades have seen death conversation-starters popping up all across the globe.

And now there are even more options to choose from — a virtual avalanche, in fact, of card and board games that prompt participants to talk about death. Since 2004, when the Bay Area nonprofit The Coda Alliance launched the card game Go Wish, several dozen companies have released games that focus on the heretofore taboo subject of end of life. And while it’s a given that all of these games offer some value — after all, anything that gets us thinking about the fact that we are all going to die is a good thing — we surmised that some would be more successful than others at getting people to talk about what matters most to them now and what they think will matter most as their lives come to an end.

So to test that hypothesis, we sat down with a group of friends (several groups, in fact) and played nine of the top end-of-life games to see what panned out. Here’s a summary of what we learned.

(Note: In the interest of an unbiased presentation, the games are ordered alphabetically.)

Our friends (from left) Richard Edwards, Jim Van Buskirk, Larry Miller and Eileen Kim play Morbid Curiosity.

Bucket List

One of the few conversation-starters we reviewed that is actually a board game, Bucket List, is the creation of Jen Davis of Ontario, Canada. A long-time hospice volunteer, Davis is a funeral celebrant, an expression coach and a firm believer in the need for more tools and resources to help people of all ages talk about death. She created her first game, Exit Matters, in 2015 with the goal of helping people who were actively planning for end of life to consider what matters most.

But that format didn’t appeal to the younger audience Davis also wanted to reach. So the following year, she created Bucket List in the hopes of reaching a younger crowd. The goal in this case, she said, was to help people in their 20s and 30s think about the questions, “What do you want to do, who do you want to be, and how do you want to live before you die?”

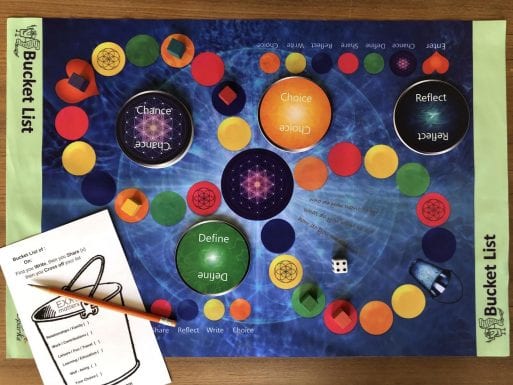

Bucket List is played like many other board games, although the “board” is actually a piece of fabric wrapped in a soft fabric pouch. Players choose a game piece, roll a set of dice, and land on color-coded circles, each of which requires them to perform an action of some sort. The rules are a bit too complex to go into all of them here, but suffice it to say that the game encourages a great deal of conversation as each player answers questions, responds to prompts, shares their thoughts and adds to their “bucket list.”

The Bucket List fabric game board is designed as an infinity loop. Players continue moving around the board until the game ends.

Our Experience

We played the game with a group of four friends, and initially we were all very confused about how to proceed. Although the board appeared fairly straightforward at first glance, we soon discovered that the game has several layers and a lot of “moving parts.” There are, for example, four color-coded groups of cards that correspond to the colored circles on the game board. When a player lands on the color, they choose a card and perform an action (for example, respond to multiple-choice questions, reflect on a question or define a value). Other circles on the board (the yellow ones) prompt the player to add an item to their bucket list, while the pink circles prompt them to share an item on their list. It wasn’t clear to us how someone would “win” the game.

Eventually, the group decided collectively to stop “playing” the game, and used the prompts on the color-coded cards to guide a conversation. From there, some lively discussion ensued. We particularly liked the open-ended reflection cards. (One example: “What do you think happens to you after you die?”)

Our Overall Impressions

All of us who played Bucket List felt that it had a great deal of potential for prompting deep, meaningful discussions about end of life. That said, we felt that it could be simplified and still retain the features that make it worthwhile. One thing we should add, however, is that our group consisted of players who were ages 45 and up. Since this game was designed with a younger crowd in mind, a group of millennials might think it’s perfect just as it is.

Strongest Feature: Great fun for younger folks

Death Insight & Conversation Cards

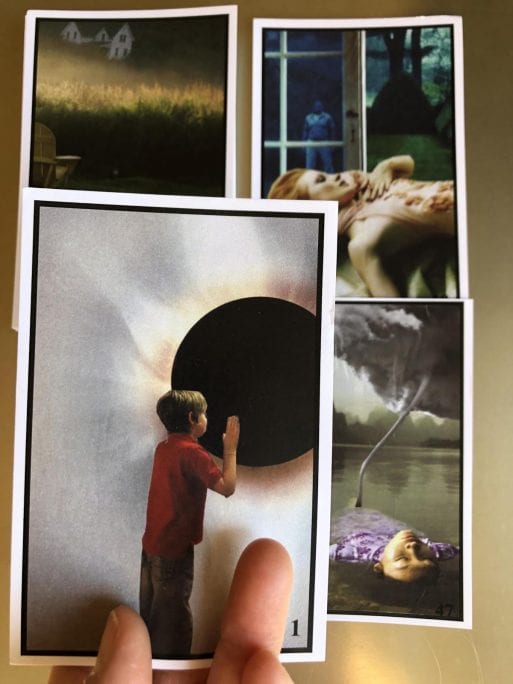

Created by certified yoga instructor, swami, death doula and celebrant Camella Nair, the Death Insight & Conversation Cards are unique among the end-of-life tools we tried. Consisting of 49 numbered cards decorated with thought-provoking collages created by Nair, the deck contains no text. Instead, the images, which are created in the “soul collage” tradition, are meant to encourage the user to “explore concepts and beliefs around change,” Nair explained. “For example, some of the cards explore our thoughts on appropriate dress code (if there is such a thing) for funerals, how we feel about our crops being poisoned, our emotions on ending relationships, etc.” she added.

The cards are accompanied by a booklet in which Nair has written some of her thoughts about the meaning of the images. She also includes suggestions for positive reflection and actions based on her knowledge of yogic mystical philosophy.

The collages on the Death Insight & Conversation Cards evoke deeply personal insights about death and mortality. Each numbered card is further explained in the accompanying text.

Our Experience

Four of us sat down to interact with the Death Insight & Conversation Cards. Because they don’t contain any textual prompts, we had some difficulty initially deciding how they might be useful in sparking conversations about end of life. But we dove in anyway, each of us picking a card from the deck that resonated with us in some way. Suzette Sherman, founder and CEO of SevenPonds, chose an image that reminded her of a tornado. For her, this evoked a deep connection to nature that she’s felt since she was a child. As she talked about that, she soon connected with her strong desire to have a window open in the room when she is dying so she can be in touch with nature and feel truly alive until the time of her death.

Not all of the players had such clear-cut associations, however. A few of us felt the cards were more spiritually evocative, and Stephen Clark said they reminded him of a Tarot deck. From there, our discussion evolved into a deeper exploration of how religious teachings and beliefs color our perceptions of what death of the physical body actually means.

Our Overall Impressions

The open-ended, non-directed nature of the Death Insight & Conversation Cards was a little bit daunting initially, but when we coupled the images with the accompanying text, some lively conversations ensued. Unfortunately, not everyone was able to relate the cards to their thoughts and beliefs about the end of life. Nevertheless, we did explore some fascinating subjects, and everyone found the cards valuable in some way. Those of us who are more visually oriented felt the deepest connection to them, much like we would when interacting with a work of art.

Strongest Feature: Perfect game for creative types

Elephant in the Room

Developed by the husband-and-wife team James Desiderati and Cindy Moyer, Elephant in the Room is not a game, per se, but a nicely designed conversation starter that’s meant to help people look in a very focused way at what they want as their lives come to an end. It consists of 96 cards divided into four main, color-coded categories: Values & Beliefs, People & Places, Definitions & Resources, and Complex Care. To add a touch of whimsy, Desiderati and Moyer designed the cards in the shape of an elephant’s foot.

The Elephant in the Room cards are shaped like an elephant’s footprint and grouped into four color-coded categories: Values & Beliefs, People & Places, Definitions & Resources, and Complex Care.

The goal of play is not to answer all of the questions in one sitting, but to explore the different categories as your level of comfort allows. Some participants, for example, might not be ready to discuss what care they might want or not want if they had dementia or advanced cancer. But they might be comfortable talking about questions such as, “What is the difference between hospice and palliative care?”

“The goal is to get people talking earlier, before a medical crisis, a traumatic illness or even an accident occurs,” Moyer explained.

Both Desiderati and Moyer have had personal experiences with helping guide loved ones through that difficult terrain. And Desiderati, a hospice nurse, has more than once come home from work and said to Moyer, “I had to talk about the elephant in the room because no one else would.” So, frustrated with the status quo, the two set out to find a better way. In August 2013, they founded Caring Choices.org, an advance care planning service based in central Pennsylvania. Then, in September 2014, they launched Elephant in the Room. Over 200 copies have been either sold or donated since that time.

Our Experience

We played Elephant in the Room with four friends. Almost immediately, we became involved in a lengthy discussion prompted by a card in the Definitions & Resources category that said: “You have told your family ‘I don’t want to be a vegetable. Pull the plug.’ Define vegetable. Define plug.” After a collective “Wow!” we dove into a conversation that ranged across a variety of topics, from living with advanced dementia to being kept alive by machines. Eileen Kim, an internist at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California, spoke eloquently of her belief that if lay people knew what went on in the ICU setting, they would choose not to continue along that path. But she also left room for the fact that some people, for a variety of reasons, might want to be kept alive at all costs.

This one card sparked a great deal of discussion — so much, in fact, that we explored only a few other cards in the deck. Still, we all felt that we had covered a lot of important ground, and that the cards helped us imagine scenarios we would never consider on our own.

Our Overall Impressions

All four of the people who participated thought that Elephant in the Room was thought-provoking and well designed. We liked the questions. They pointedly addressed many different areas that the average person might not consider when thinking about how their lives might change as they approached the end of their lives. As Kim said, “It gets to the meat of the matter” — the nitty-gritty details that become terribly important when we are seriously ill.

The one downside we saw is that we did not have enough time to delve deeply into all of the categories. So if you’re considering purchasing Elephant in the Room, keep in mind that it’s a tool you can, and should, use over and over again.

Strongest Feature: Great tool for those with a life-limiting illness

Go Wish Cards

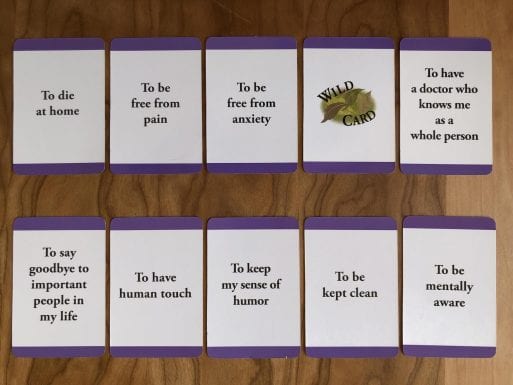

One of the first conversation-starters to enter the end of life landscape, Go Wish is still one of the most widely used. Consisting of 36 cards, each one identifying an issue that might concern someone who is facing the end of their life, the game asks participants to choose the 10 things they believe will be most important to them as they approach death. In some versions of the game, the remaining 26 cards are ordered as “Somewhat important” and “Not important.” But when we played, we chose to concentrate only on identifying what was most important to us, ordering them from No 1 to No. 10.

A player’s top ten Go Wish cards placed in order of their importance.

Initially developed to help nursing home and assisted-living residents with limited cognition to clearly and easily communicate their end of life wishes to caretakers and family, Go Wish cards have become a staple in the toolbox of many doctors who care for the seriously ill. They’re also a favorite tool of many professionals who are working in various capacities to help more people talk about the end of life. Dr. Dawn Gross, M.D., Ph.D., a palliative care physician and former host of KALW’s “Dying to Talk” radio, calls the cards “an essential tool of my trade” and carries them in the pocket of her white coat, just like her stethoscope. In fact, when she was asked to be a healthcare advocate for a very good friend, she responded that she would be honored to do so, but only if the friend played Go Wish with her first. “An advance directive alone isn’t sufficient to fully communicate a person’s values and wishes,” Gross explained. “I wanted to have a conversation first.”

Our Experience

Four of us sat down with the Go Wish cards and took a few minutes to choose the 10 cards that were most important to us. Everyone found the cards to be very clear and easy to understand, but the challenge of choosing only 10 items and prioritizing them was more daunting than we thought it would be. “I want all of them!” said Jim Van Buskirk, a facilitator who regularly conducts death cafes.

Once everyone had made their choices, we shared our answers, and a lively and sometimes poignant discussion ensued. At one point the conversation turned to the issue of competence and dementia, and we talked about how we might ensure that our wishes were honored if we became mentally impaired. We also talked about dying alone versus dying with our loved ones present, which turned out to be an area in which some of us strongly disagreed. For Sherman, the prospect of dying alone is so terrifying that it actually “keeps me awake at night.” But Van Buskirk expressed the exact opposite sentiment. “I don’t want to be taking care of someone else while I’m dying,” he said. “I want the focus to be on ME!”

Our Overall Impressions

All in all, our group thought the cards were an extremely effective tool for getting people talking about the end of life. Despite its simplicity, Go Wish prompted a very focused and productive discussion, even without all the “bells and whistles” of some of the other games we played. That said, we agreed that it is most appropriate for people who are older and beginning to think about their own mortality, even if they are not close to death. We felt that younger people could also benefit from playing Go Wish, but thought they might enjoy some of the other games more. (That said, Gross uses the deck in a death education class for high school students, so we may be wrong!)

Strongest feature: Excellent for decisions about active dying

Hello

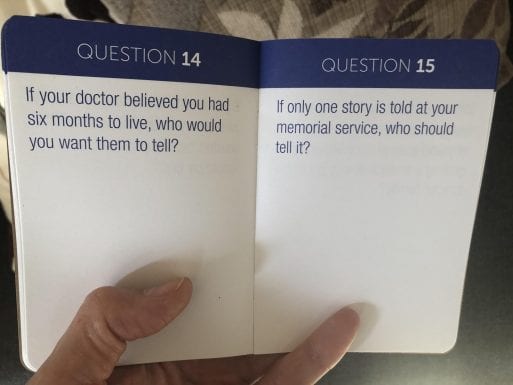

The second iteration of a conversation starter game from the design firm Common Practice (the first was called My Gift of Grace), Hello is a simple-to-use tool to help families, friends and healthcare practitioners begin a meaningful discussion about end of life goals. Created by Common Practice co-founder Nick Jehlen, the home version of the game consists of five booklets with 47 questions each and 30 “thank you” chips. The questions are meant to be answered in order, and, as Jehlen said, “everyone plays.” So if a doctor and social worker sit down with a patient to play Hello, they answer the questions too.

A player reads the questions in the Hello game booklet before writing down his answers.

The game starts when a player reads the first question aloud, and all players write their answers in their books. When everyone is done writing, each player shares their answer with the group if they choose to do so. If a player finds an answer particularly helpful, they may give the person who shared that answer a thank you chip. At the end of the game, the player with the most or fewest thank you chips wins. (This is decided by a coin toss at the beginning of the game, but the players don’t know the result until the game is over.)

The goal of Hello is to answer the questions in order. That said, there are a lot of them, so your group may not answer them all in one sitting, especially since the goal is to share stories and talk. According to the rules, the group should set a time limit at the start of play. That said, anyone can announce that they’re ready to stop playing at any time. Then the group finishes their answer to the last question and play ends.

Our Experience

We played Hello with several friends, all of whom found the questions provocative and emotionally relevant. In some cases, players told stories of their own experiences that were quite poignant and difficult for them to share. This storytelling led to long conversations about how others thought they would react to similar circumstances in their own lives. We did not use the thank-you chips all that often, though we might have done so if we had played a bit longer. Some of us found them very meaningful, while others thought they didn’t add a lot to the game.

Patti Goldstein (left), artist and activity director at The Oakland Rehabilitation Center, shares the difficulties she and her family are experiencing as their 95-year-old mother’s health deteriorates. As Goldstein said, “She wants to die and I agree with her. That’s what makes me so very sad.” To her right is Leslie Dietterick, a project coordinator with the East Bay Conversation Project.

One card in the Hello deck that prompted a fair amount of discussion was No. 7, which says: “Name the three-person committee who should be consulted on any decision about whether to continue life-saving care if you can’t communicate. Circle the head of the committee.” One of the players, a palliative care physician who has been active in developing end-of-life planning tools, objected to the question because she believes choosing a single healthcare proxy is essential to ensuring good end of life care. Eventually we moved on to other subjects, but the question of the appropriateness of the card remained unresolved.

Then, in preparing this article, we reached out to Jehlen to get his thoughts on this particular card. Here is his response:

“People often get stuck when asked directly to name a healthcare proxy, and this question is designed to help with that challenge. Rather than naming a single person right off the bat, the players narrow their choices to a shortlist first. Then, the second half of this question narrows the player’s answer further: ‘Circle the head of the committee.’ This method: narrowing before making a final choice is a common decision-making method that helps people get unstuck when faced with a challenging decision. This also reflects the process that many people use to make decisions: by consulting with others for information and support.

“Hello is also meant to spur conversation, and this question often reveals important relationships among friends and families that will come into play when end of life decisions are being made. A single healthcare proxy is necessary, and we’ve found that using this decision-making technique and sparking conversations about trust and values leads to a more meaningful exploration of the relationships involved in these decisions.”

Later, Jehlen also pointed out that the exercise often helps people realize who they don’t want to be their healthcare proxy — a process that is equally as important to deciding who would be the best choice.

Our Overall Impressions

In general, our group liked the Hello game a great deal. We thought the questions were thoughtfully designed to spur participants to share things with each other that they would probably never reveal if they hadn’t played the game. We agreed that it is appropriate for most people regardless of their age, and that it would be particularly useful for a person who has a life-limiting diagnosis who wants to communicate their values and goals to the people who might be responsible for making decisions about their care.

(Listen to Jehlen talk about a young boy named Nazea who played the game with his caregivers and family shortly before he died in this video from 2015. )

Strongest Feature: Fun, versatile tool for end-of-life discussions

Morbid Curiosity

Part conversation-starter and part trivia game, Morbid Curiosity is the brainchild of Kimberley Mead, a grief and trauma therapist based in Austin, Texas. Mead initially conceived the game when she was working with grieving children and adults and became increasingly aware of how difficult it was for them to even talk about death. She wanted to create a tool that would facilitate those kinds of conversations, and so she and her now-fiance James Young began crafting the game in 2014. Then, with the help of a successful Kickstarter campaign, they printed the first version of the game in 2017.

Playing Morbid Curiosity is pretty straightforward. Players choose from two decks of cards: trivia cards and discussion cards. When a trivia card is in play, the player who gets the right answer first is awarded the card. (The correct answers are on the bottom, which is helpful, since the questions are pretty arcane!) When a discussion card is in play, the person who picks the card reads it aloud and all of the players answer it. The person who reads the card chooses the answer they like the best, and the player who gave the answer gets to keep the card. Play ends when one player has accumulated seven cards.

A player selects a Morbid Curiosity card from the black “Trivia Card” pile.

Our Experience

We played Morbid Curiosity with four friends, and everyone caught on quickly and enjoyed playing a great deal. That said, while we thought the trivia cards were fun, we found the discussion cards to be better conversation starters even when we struggled with the answers a bit. One card, for example, asked, “What was the most surprising thing that ever happened at a funeral you attended?” At first, no one could think of an answer. But then Jim Van Buskirk recalled a time when he was officiating at a funeral during which a song recorded by the person who died was played. “I completely fell apart,” he said. “I was sobbing so hard I had to stop the service for a while.”

Another question asked whether we would ever combine the cremation ashes of two people we loved. That, too, sparked a lot of discussion, which eventually evolved into a heartfelt conversation about honoring the wishes of a person who died versus honoring the wishes of someone who is still alive.

Our Overall Impressions

All of us who played Morbid Curiosity enjoyed the game a lot. We loved the design of the cards, which are decorated with an intricately drawn death’s head moth in which a tiny cemetery is cleverly hidden in the wings. (The design was created by Seattle-based mixed-medium artist Prem Krishnan.) Again, we thought the discussion cards were better conversation starters, but the trivia questions were quirky and challenging and we had fun trying to answer them. (Did you know that the phrase “dead as a door nail” was coined by William Langland? We didn’t either!)

Strongest feature: Most fun for cultural discussions

Now and Then

Created by the design firm After, Now and Then is a board game that aims to bring friends and family together to discuss their goals, values and wishes around the end of life. It is one of three tools offered by co-founders Joseph Weissgold and Divine Bradley. The others include a Starter Pack, which is meant to introduce someone who is new to the conversation to the “25 questions” they should be asking as they think about end of life, and a Legacy Workbook, which guides the user through a series of tasks intended to help them create an Advance Directive and a Last Will and Testament.

Now and Then is a complex game, with lots of layers and lots of moving parts. Like the Starter Pack, it focuses on four main topics that you need to consider as you plan for your death: Care, Body, Ceremony, Treasures and Legacy. At the start of the game, each player writes a table of contents for their life story, starting with before they were born and ending with the present day. As the game proceeds, players draw cards from the different categories (based on a complex set of rules) and share their answers. The other players then write a few words of feedback or appreciation on a plain white “read back” card.

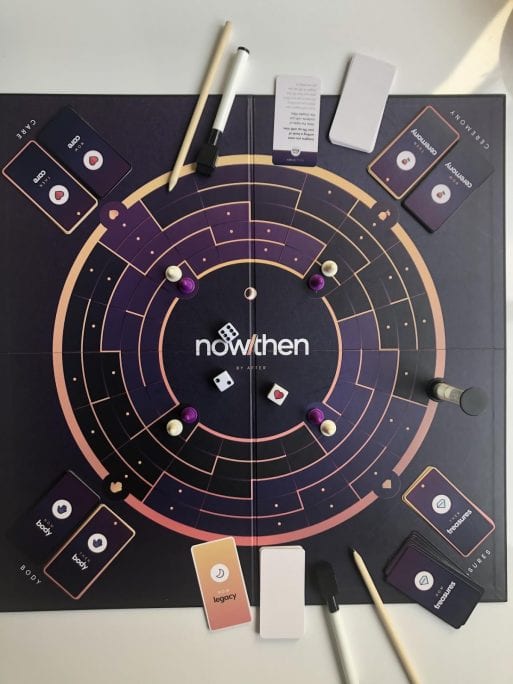

The Now and Then Game being set up for two players to begin.

The questions themselves are very provocative and really help to spur a discussion of values and goals. For example, in the category Ceremony, one questions reads: “They want your memorial or funeral to reflect your personality. Describe any details or activities that could be incorporated.” One of our friends, Richard Edwards, whose girlfriend died of cancer many years ago, gave this answer: “I would incorporate it outdoors with good food and drinks at an archery range. I’d have graphic designs of things I like such as cowboy hats or toy guns on the bullseye. I’d give my meaningful objects to certain friends.”

We played Now and Then with two different groups, and our overall experience was that the game had so many bells and whistles that it was hard to delve into it right away. Even after reading the directions several times, we regularly had questions about how to proceed. For example, each question card has two symbols that affect how the card is played. We often had to refer to the instructions to determine what each symbol meant.

That said, we thought the game was beautifully designed and thought-provoking, and the more we played the better we understood the various permutations of the board and cards. We especially liked the way that the different categories were ordered methodically to help us explore topics in a logical way. For example, a card in the Care category reads: “They are moving you to a place where you can get more attentive care. Talk about the kind of place you want.” Another card, in the Treasures category, reads, “They are going through all your old boxes. Talk about which of your possessions should go to one person or another.”

Our Overall Impression

Despite the technical challenges, we thought that Now and Then was successful in helping us consider the things that we need to think about as we approach the end of life, from funeral arrangements to who we want to have the things that mattered most to us when we were alive. We also enjoyed the read-back cards, which gave each of us the opportunity to support, encourage or offer words of advice after hearing our friends’ thoughts.

Strongest Feature: Fun game with lots of bells and whistles

The Death Deck

Created by author/entrepreneur Lori LoCicero and hospice social worker Lisa Pahl, LCSW, The Death Deck is a “party game that lets you explore a topic we’re all obsessed with but often afraid to discuss.” Consisting of 112 cards with a mixture of open-ended and multiple choice questions, it is simple to play, easy to understand, and has a tongue-in-cheek look and feel that is definitely aimed at a young-ish crowd. Some of the questions are serious (“What would you do on your last day on earth and who would you do it with?”); some are rather silly (“Who of your enemies would you choose to haunt after your death?”); and a few miss the mark entirely. But overall the game meets its goal of making talking about death fun.

There are two options for playing the game — with a partner or in a group. If you play with a partner, your team scores a point when you both provide the same answer to one of the multiple choice questions on the “Final Answer” cards. If you are playing in a group, each person picks a card from the deck and reads it aloud. The other players take turns guessing which answer the person will choose, and the players who guess correctly score a point.

A player holds a Death Deck “Final Answer” multiple choice card. The Dig Deep cards, which ask more thought provoking questions, are on the right.

Our Experience

We played the Death Deck game with a small group of friends, most of whom are over the age of 50. Although we thought some of the questions were thought-provoking, for the most part we thought the game was just a bit too “hip” to appeal to an audience in our age group. From the design of the cards (which sport a simply drawn skull with an upside down heart for a nose) to the headings on the cards (On the Rack, I See Dead People, and Necrophilia, for example) we got the sense that we were playing “death poker” or a college drinking game rather than a conversation-starter about death.

Our Overall Impressions

Although the Death Deck might be lots of fun for people in their 20s and 30s, our group thought it fell short of what we wanted in a game aimed at helping us have a productive conversation about end of life. We also felt that some of the questions could be upsetting to people who were dealing with the impending death of a loved one or their own failing health. That said, the game is obviously designed for a younger audience, so we may not be the best judges of how successful it is.

Strongest feature: Fun game for young “immortals”

Your Life Wishes & Your Life Story

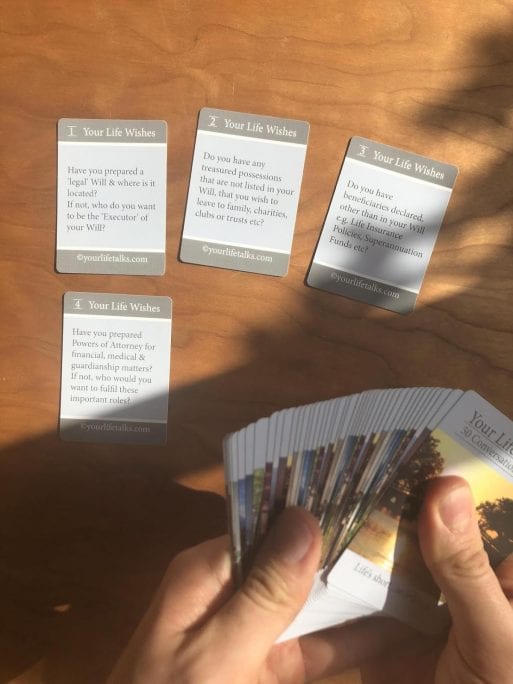

Offered by the Australian advance planning organization Your Life Talks, Your Life Story and Your Life Wishes are two decks of 50 cards each that strive to get people talking about their lives and their inevitable deaths. They can be played in the same sitting or at different times — each one has a distinct flavor and goal. Your Life Story encourages participants to answer questions about their lives, such as, “Where were you born?” “Who were you named after?” and “What is your nickname and how did you get it?” Your Life Wishes, on the other hand, is a very concrete game that walks the players through a series of questions about end-of-life planning, from whether they have a written will to what’s on their bucket list.

A player holds the Your Life Wishes Cards. The cards are played in numerical order to methodically walk players through the steps necessary to prepare for end of life.

Our Experience

We sat down with four friends and played both games. We started with Your Life Wishes, and it soon became apparent that the pointed questions were more or less a roadmap for preparing yourself personally and financially for the end of life. The questions are pointed and, in some cases, very basic (for example, “Have you named a healthcare advocate?”). But as we moved through the deck, they became more nuanced and led to some lively conversation about how we were preparing or not preparing for our own lives’ end.

When we moved on to Your Life Story, we found the questions to be thought-provoking and fun. We spent some time talking about our childhood nicknames. (All of us related to Clark’s comment that the only time anyone called him by his full given name while he was growing up was when his mother was angry with him.) Then Colleen Paretty, editorial director for WebMD magazine, picked up a wildcard that asked her to “talk about something you’ve always wanted to know.” Her answer — “Is there an afterlife?” — spurred a long conversation in which another player, Mary Hulme, shared a story about a premonitory dream her mother had on the day her two sons were killed in a plane crash. Hulme, who runs Moonstone Geriatrics , said her mother’s vivid dream convinced her that something happens after death that we don’t understand.

Our Overall Impressions

All of us who played these games felt that they were thoughtfully and carefully designed. We liked the questions: Clark, who is living with a life-limiting illness, remarked that they were what he wanted to know when he was diagnosed.

That said, we didn’t care for the card face all that much — we thought the image seemed a bit like what you might see on a sympathy card. We also were a little put off by the branding — each card is printed with the copyright yourlifetalks.com, which we thought was a bit much. Still, we found both games to be worthwhile and we agreed we would play them again.

Strongest feature: Great game for getting your affairs in order

The Wrap Up

Obviously, the array of end of life conversation starter games is wide and growing. We loved playing all of them, and — as an organization that focuses on end of life — we find it encouraging and exciting that these games and other conversation starters are being embraced by the public at large. We have a long way to go, of course; according to a study published in the journal “Health Affairs” in 2017, about one in three American adults has completed an advance directive for healthcare, which means that almost 70 percent of us have not. What’s more, it’s almost a given that many of the people who have filled out these documents have not had the kind of deep, reflective conversations with their loved ones that are necessary to truly communicate wishes and goals.

This is especially important when designating a decision-maker, explained Gross, the palliative care physician and former radio host. “Many healthcare systems/hospitals focus on making sure patients have named at least one surrogate decision maker,” she said. “This objective, taken in isolation, can be problematic. Meaning, if a person writes down a name of another person and declares that they are their decision maker without ever having had a conversation that explores their values and wishes, a lot of unintended distress and even trauma can result,” she added.

Still, there is some evidence that more people are talking more about their goals and wishes for the end of their lives. According to a national survey of over 1,000 Americans conducted by The Conversation Project in 2018, there has been an increase of about 5 percent in the number of adults over the age of 18 who have had a conversation about their end of life wishes with loved ones in the past five years. And according to The Conversation Project Senior Director Kate DeBartolo, that organization has provided more than 1 million free “Starter Kits” to people in over 200 countries since its founding in 2010.

“We do think the trend is continuing to grow,” DeBartolo said. “The more we normalize these conversations, the more folks are open to sharing what matters most to them… People are more open to the concept. Once they are open to it, we hear that our Conversation Starter Kit and other tools are really helping people think through their wishes and figure out how to talk about them in a productive way with those who matter to them,” she added.

That sentiment was echoed by Gross, who said, “The increasing variety of new entry points (games, festivals, feasts, cafes, etc) that invite people into conversations about what matters most at the end of life is unquestionably helping our society engage in a conversation that had become taboo.”

We at SevenPonds wholeheartedly agree. As our friend Jim Van Buskirk said during one of our get-togethers, “People are starving for a safe place to talk about death.”

These nine games are certainly an excellent starting point.

People Are Playing Games to Help Them Talk About Death

People Are Playing Games to Help Them Talk About Death

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition