Credit: Markus Spiske

Mental health professionals are increasingly encountering a phenomenon known as “climate grief” or “eco-anxiety.” These and other similar terms refer to the depression, mourning and overwhelm resulting from global warming and its effects on our planet. A March 2019 Gallup Poll found that 44 percent of American adults worry a “great deal” about climate change.

Ashlee Cunsolo, director of the Labrador Institute of Memorial University in Canada, told PRI’s The World that what she terms “ecological grief” spans everything from the trauma of severe weather events to the “pain and suffering of watching a beloved place change.” Cunsolo noted that part of the difficulty of grappling with climate grief comes from the fact that we have no rituals to mourn the loss of places or species, the way we do with friends or family members. In this sense, it is a form of disenfranchised grief.

Residents in the world’s most affected areas, such as Inuit communities in the Arctic, report notable losses in their daily lives. In Greenland, a recent national study found that 82 percent of residents consider climate change personally important, with about half believing that its effects will harm people, plants and animals there. Courtney Howard, the board president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, says the climate emergency’s health impact is of global concern. “There is no question Arctic people are now showing symptoms of anxiety, ‘ecological grief’ and even post-traumatic stress related to the effects of climate change,” she told The Guardian.

Earth’s Devastation Causes Climate Grief

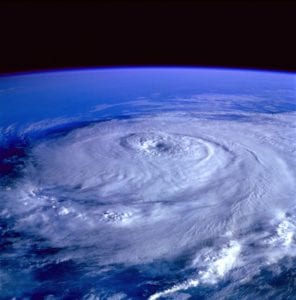

A 2017 report from the American Psychological Association found that long-term climate changes can prompt “fear, anger, feelings of powerlessness, or exhaustion.” Witnessing regular environmental and ecological disasters – whether Hurricane Dorian’s devastation in the Bahamas, species extinctions or widespread fires in the Brazilian Amazon – has an impact. When the U.N. released its climate report last year, calling for “unprecedented” action to prevent catastrophic consequences in the next 12 years, psychologists reported new, adverse reactions from patients.

Severe weather events cause climate grief

Most of us have gone through the stages of grief following significant losses in our lives, including the death of loved ones. Yet climate grief involves an existential crisis on a much larger scale. “On some level, I am thinking about climate change all the time,” one woman wrote in a personal essay for Vice. “I think about it every time someone in my life has a baby, and I wonder what the world will be like when that baby is the same age as me.”

Dr. Lise van Susteren, a psychiatrist who co-founded the Climate Psychiatry Alliance, told NBC that many people have reached a tipping point in the way they perceive climate change. “For a long time we were able to hold ourselves in a distance, listening to data and not being affected emotionally,” she said. “But it’s not just a science abstraction anymore. I’m increasingly seeing people who are in despair, and even panic.”

Van Susteren added that it’s important for people to talk about climate grief and anxiety – to get it out in the open. By doing so, psychiatrists and psychologists hope those affected will be able to build resilience, create community and take more effective action.

People Are Struggling with “Climate Grief”

People Are Struggling with “Climate Grief”

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One