Credit: medicinenet.com

As we begin the year 2018, heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States, killing over 600,000 Americans every year. More than half of these deaths are due to sudden cardiac arrest, usually caused by a fatal disruption of the heart’s normal rhythm known as an arrhythmia. Fewer, but still a significant number, occur following a heart attack.

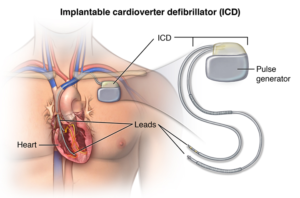

Yet, thanks to medical advances such as implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) and left-ventricular assist devices (LVADs), a growing number of people are surviving with advanced heart disease for many years. According to a recent article in the New York Times, the number of people living with severely diminished heart function (a condition known as heart failure) rose to 6.5 million between 2011 and 2014.

Sadly, this longer lifespan is leading to a growing crisis: the failure of healthcare providers to prepare people with heart disease for their ultimate deaths. Once a swift and predictable killer, heart disease now follows an uneven trajectory. Many patients survive well into their 80s, albeit with shorter periods of feeling well and more time spent in hospitals and emergency rooms. Yet even when death is near, doctors are unlikely to refer them for palliative or hospice care. In fact, only 15 percent of hospice deaths in the United States are the result of heart disease, while cancer accounts for more than half.

Misplaced Optimism and Technology Combine

The reasons why doctors fail to refer patients with advancing heart disease to hospice and palliative care are complex, according to a number of providers interviewed by the New York Times. For one thing, the progression of heart disease, even in its later stages, can be quite unpredictable.“The issue is knowing who is really at the end of life,” said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a Yale University cardiologist. Patients often seesaw between being very sick and feeling relatively well. “It is confusing to both the patient and provider,” added Dr. Ellen Hummel of the University of Michigan, who specializes in cardiology and palliative care. “Are they actually dying, or can we rescue them from a particular episode of worsening?” she said. With the availability of medical devices that can postpone death almost indefinitely, this distinction has become even more difficult to make.

An implantable cardioverter defibrillator

Credit: indiahealthhelp.com

Another issue that keeps cardiologists from discussing end of life issues is their unwavering focus on saving lives. Cardiologists view themselves as doctors who bring patients back from the brink of death, according to Dr. Michael Bristow, a cardiologist at the University of Colorado in Denver. “Those who go into cardiology are not necessarily ones who want to deal with death and dying,” he said. Couple this with the fact that most doctors are overly optimistic about their patients prognosis, and it’s somewhat understandable that cardiologists, in particular, avoid the subject of end of life.

Overly Aggressive Care

Yet, as understandable as the reluctance of cardiologists to discuss hospice with their patients may be, the harmful results of these omissions are clear. According to a study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology in September 2017, patients with advanced cardiovascular disease are “more symptomatic, less likely to die at home, and less likely to receive high-quality palliative care” than other patients approaching the end of life. In fact, as many as one in five patients with implanted defibrillators receive shocks to their hearts during the last weeks of their lives. Even more alarmingly, 8 percent of patients with internal defibrillators receive a shock within moments of their deaths. According to the Times, most patients are never even informed that they have the ability to turn these devices off.

New Standards Needed

Credit: ameritech.edu

All of the cardiologists interviewed for the Times article agree that end-of-life discussions are critical for patients with advancing heart disease. Yet they also agreed that there are no clear-cut standards to help doctors steer their focus from aggressive treatment to palliative care. In late-stage cancer, the illness trajectory tends to be fairly straightforward, Dr. Hummel explained. The patient gets progressively weaker, and their level of disability worsens predictably. “Most people can see the end coming,” she said. But in heart failure, these markers of increasing disease severity may be harder to spot.

Still, no one can argue that dying patients should be subjected to electric shocks to restart their hearts. “We shouldn’t have a single one of these cases happening,” said Dr. Haider Warraich, a cardiology fellow at Duke University and the lead author of the study. Obviously, someone needs to take responsibility for making sure that people with heart failure get appropriate care and the information they need to make proactive decisions about how and where they would like to die. And if not the cardiologist, then who?

People with Heart Disease Miss Out on Palliative Care

People with Heart Disease Miss Out on Palliative Care

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?