Dr. Barak Gaster, who works as an internist at the University Of Washington School of Medicine, was concerned about his patients with dementia. Yes, many of them had advance directives, but mostly advance directives are written with a sudden catastrophic condition like a heart attack, stroke or car accident in mind. He wanted to create a dementia-specific advance directive.

Credit: theodysseyonline.com

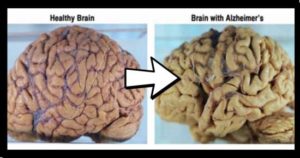

Dementia is a slow killer, lasting anywhere from five to 20 years. It is roughly divided into three stages. In the first stage, people experience memory loss for recent events, such as forgetting that a son had visited earlier that day. Routine tasks such as bathing, dressing, and driving become difficult if not downright dangerous.

In the second, or moderate, stage of dementia people start forgetting words and communication becomes limited. The person with dementia may not to be able to recall important people like an adult child or a spouse. He or she may also confuse one person with someone else, like thinking a daughter is a deceased spouse. The person loses the ability to dress appropriately and to toilet themselves. He or she probably needs care several hours a day.

By the third or severe stage, most people are unable to remember any of their loved ones. Lost in a world where nothing is familiar, they may strike out at caregivers or scream the same phrases over and over. Many people spend all of their time curled up in bed. The body starts to forget how to function, and hospice may be involved due to weight loss or breathing problems.

Dr. Gaster reasoned that people with early stage dementia might want more aggressive care than someone with moderate to severe stages. He worked for three years with experts in the psychiatric, neurological and geriatric fields. The result was the dementia specific advance directive. Gaster’s patients use it in addition to rather than instead of other advance directives such as living wills and durable powers of attorney for health care.

Dementia Specific Preferences

The document consists of five pages. It explains in simple terms what each stage of dementia looks like. Then, for each of the three stages of dementia, people can choose from four treatment options: full treatment including CPR and a respirator, full treatment except for CPR and artificial breathing, treatment that can receive at home, and comfort care only.

Credit: positivemed.com

If you choose to complete a dementia specific advance directive, do so while you are still competent, and talk to your loved one’s about your preferences. Start with a statement like, “If I ever get to the point where I don’t know you…” Make sure the person who will act as your health care agent if you become incapacitated knows about your wishes. Your primary doctor should be part of this conversation as well.

Not all healthcare providers see the need for a dementia specific advance directive. Some believe they are confusing or redundant. Dr. Gaster and his colleagues, though, stand by their observations and research. Gaster believes that dementia is a missing piece in most advance directives, and that many of his patients will welcome the chance to communicate their preferences before they start showing symptoms.

If you would like to look at a dementia specific advance directive, or if you would like to download one to complete, click here. Tell the people you love about what kind of care you want. Don’t make them guess.

The Benefits of a Dementia Specific Advance Directive

The Benefits of a Dementia Specific Advance Directive

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?