How would you feel if you had to bury a friend or family member who had been killed in a school shooting? What if you had been one of the lucky ones who survived the actual event? The burden of the survivors of school shooting victims echoed last month when, within 10 days, three people who had lost a friend or loved one in a school shooting took their own lives.

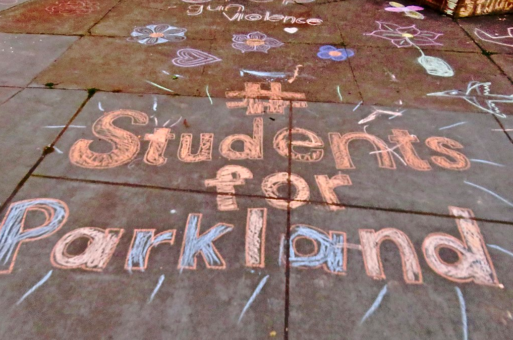

Credit:@field.complete via Instagram

A 2018 graduate of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, where 17 died by the act of a lone gunman during her senior year, killed herself on March 17. Thirteen months had passed since her best friend was counted among the dead in the mass shooting. Before the week of her death ended, an unidentified male Marjory Stoneman High School sophomore took his own life as well.

Within 48 hours of the second tragic death in Parkland, news broke of an apparent suicide of a Connecticut father who lost his 6-year-old daughter in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting over seven years ago. Gunfire killed 20 children and six adults in Sandy Hook in 2012.

While bullets take lives of school shooting victims on site, these three deaths that occurred within 10 days of each other are reminders of how complicated grief can add to the toll. Twenty-eight percent of survivors of the initial event suffer PTSD (as with the Parkland grad). Many go undiagnosed (as with the undergrad). Some even have directed their energies to actively advocating violence prevention (as with the Sandy Hook father, who had established a non-profit foundation after his child was killed.)

Degrees of Separation Lessen With Each School Shooting

Last year the New York Times reported that there have been at least 239 school shootings nationwide since Sandy Hook. Sixteen can be classified as mass shootings — events in which more than four were shot.

Through them all, a total of 438 people have been shot, 138 of whom were killed. If you multiply those killed by their many close survivors, you are left with hundreds to perhaps thousands of children and adults in bereaved communities who may be at greater risk of suicide due to their loss. If we go back to the initial school shooting that shocked America — Columbine in 1999 — more than 223,000 children have experienced gun violence at school. (Documented cases of survivor suicides occurred after Columbine and the Virginia Tech Shooting in 2007 also.)

Even advocating against gun violence doesn’t always mitigate the guilt felt by those who survived a school shooting

Survivor’s Guilt

Being directly affected by a mass shooting is certainly “a risk factor” for suicide, according to Heather Littleton, a professor of psychology at East Carolina University who specializes in recovery from trauma. In an interview with Atlantic magazine last week, Littleton added that recovery can be made harder by a prevalent misconception that grieving is a linear, incremental process that can be completed within the months or years after a tragedy.

Mass shootings often result in a particularly difficult kind of grief known as traumatic grief, which Littleton describes as a PTSD reaction that occurs when someone is grieving over another person’s violent or unexpected death. As with PTSD, “a traumatic-grief reaction could last for a number of years… (and) those traumatic symptoms then interfere with the resolution of the grief reaction.” The result is commonly known as “survivor’s guilt.”

“The person sort of gets stuck on this idea that ‘I should have been able to prevent this death,’ or ‘Why did this person die instead of me?'”

What Can Family and Friends Do?

For these survivors, time does not heal the loss. In fact, it can increase the distress, especially as “anniversaries” of the shooting approach and pass. This brings up the question of — beyond well-intended thoughts and prayers immediately after a traumatic loss — what can others do to support the surviving community members?

CNN offered some suggestions in the wake of last month’s suicides. Along with having access to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255, those of us close to survivors need to inquire about their emotional well-being instead of being reluctant to talk about their traumatic experience directly. We need to stop assuming “time heals.”

Ryan Petty, who lost one child in the Parkland massacre and has another who survived, suggested to CNN that parents and close friends use questions from the Columbia Protocol on suicide risk assessment to help save lives. These questions include:

— Have you wished you could go to sleep and not wake up?

— Have you thought about hurting yourself?

— Have you thought about how you might accomplish this?

The beauty of those questions is parents and close friends don’t need to be trained therapists to ask them, says Petty.”They can be part of the solution…We really need to drive awareness.”

An essential part of that is understanding the nonlinear nature of grief that Littleton spoke of: the fact that grief can ebb and spike over time rather than steadily decrease. As Petty warns, “We need to make sure that everyone, especially parents, understands their child or loved one may be at risk” and that we can more likely get them to the professional help they need if we talk to them about their feelings directly.

Three Suicides Last Month Connected to School Shootings

Three Suicides Last Month Connected to School Shootings

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead