Joan Fellows wasn’t sure what to say to a neighbor after learning his wife had dementia.

For some, it starts with communication problems; for others, it’s forgetfulness. When a friend learns their spouse has dementia, they find themselves at the beginning of a long and often harrowing journey — one characterized by grief, loss, isolation and loneliness.

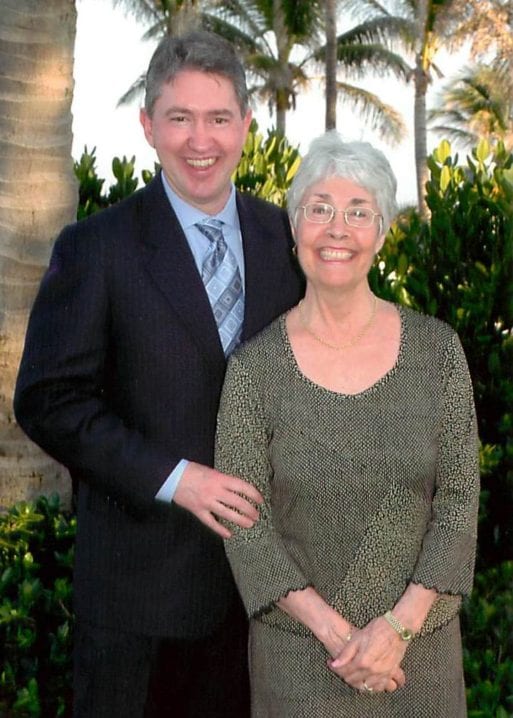

Kevin Jameson with his wife, Ginny

Kevin Jameson and his wife, Ginny, had been seeing a marriage counselor for about a year when the counselor pulled him aside to tell him there was likely something else going on. Several years later Ginny, in her 60s, was diagnosed with an undetermined form of dementia. “It basically became a matter of keeping her safe and finding ways to live through the progression of what was coming — and quite frankly, I didn’t know what was coming,” Jameson said. As Ginny’s condition worsened, Jameson had people come into the home to prepare meals, provide companionship or otherwise care for her. Then professional caregivers began living at the house. Eventually, she moved into a secure dementia community, followed by a nursing home; then hospice, where she died in 2014.

Initially, Jameson lost much of his social circle, though some returned as he educated them about Ginny’s condition. “The number one thing that I would say to family and friends is: Open your eyes to the reality of what dementia can mean. And if you’re able to, embrace the changes and go with it, go with the flow. Because that person still needs you in their life.” Shortly before his wife died, Jameson founded the Pennsylvania-based Dementia Society of America to help people understand dementia and prepare for its impact. He now serves as its volunteer president and CEO.

Jenny Heuer works with dementia

patients and their families

Spouses of those with dementia are confronted with what’s commonly called “the long goodbye” — the ongoing loss of emotional and physical intimacy with their partner. “The emotional intimacy I think is the biggest change,” said Jenny Heuer, a certified dementia practitioner and licensed professional counselor specializing in gerontology in Atlanta, Georgia. Couples often “enjoy kind of sparring and arguing about movies or religion or politics, and they just can’t anymore because of the individual’s ability to process.” Many become even more isolated as their support systems disintegrate. “A lot of times friends and family may walk away from that person because they don’t understand dementia, and they have this idea that it’s a scary disease,” Heuer said.

In addition to grief and isolation, spouses typically encounter numerous challenges related to their shifting role in the home. “People have their roles and responsibilities that they fulfill, that you don’t even think about on a daily basis,” said Rebecca Logsdon, a research professor emeritus at the University of Washington’s School of Nursing who specialized in gerontology and geriatrics. Often, a wife will handle household chores such as cooking and laundry. Sometimes, a husband will do the driving or banking. “Now, all of a sudden, the person that you count on to do something for you is not able to do it — or doing it wrong,” she said.

The U.S. National Institute on Aging defines dementia as “the loss of cognitive functioning — thinking, remembering, and reasoning — and behavioral abilities to such an extent that it interferes with a person’s daily life and activities.” While Alzheimer’s disease is the most common and well-known cause of dementia, there are various other forms, including Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia and frontotemporal disorders. More than 16 million unpaid caregivers, including family members, spent an estimated 18.6 billion hours caring for people with dementia in 2019, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. The organization estimates that more than 5 million people aged 65 and older are living with Alzheimer’s dementia today, and that this figure could more than double by mid-century.

People often don’t know what to say to a friend whose spouse has dementia. Joan Fellows, who lives in a Florida retirement community called The Villages, found herself at a loss for words when she ran into her neighbor at the pool after learning his wife had dementia. Meanwhile, adult children and other family members who wish to provide support typically don’t know where to begin. How should they respond? What can they do? Experts say there are many ways to help. Fortunately, the most significant is also the most simple: Just show up.

The Right — and Wrong — Words When a Spouse has Dementia

Experts agree that the willingness to be present and listen is the most effective assistance one can offer to a friend whose spouse has dementia. “You want to be a listener more than anything, and a partner,” said Kathy Stewart, vice president of nursing and care at Aegis Living, which operates long-term and respite care facilities in California, Washington and Nevada. “You have to walk the path with them, and meet them at the place that they are.” Still, in the beginning stages, Stewart said it’s essential to encourage a spouse to take their partner to the doctor and obtain an appropriate diagnosis. “That would be the first thing,” she said.

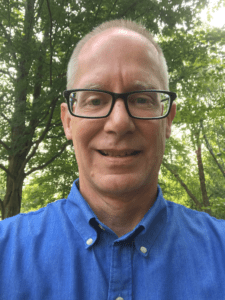

Dr. Monica Parker

Credit: Emory Medicine Magazine

Dr. Monica Parker, an assistant professor of neurology at Emory University’s School of Medicine in Atlanta, said that people can be screened for both depression and dementia at their annual medical visits, and that any unusual behavior — such as not eating enough or wandering off at night — should lead to an immediate professional consultation. “Dementia is like a drip in the ceiling. One or two drops you don’t see, but when the ceiling starts to get discolored you see that there’s something up there,” she said. “You go and get it addressed.” Once a diagnosis has been obtained, Parker said family members can also encourage a spouse to get their legal documents in order, including a power of attorney and advance directive. She emphasized that it’s important to encourage spousal care partners to seek out training so that they don’t become frustrated or overwhelmed and are made aware of what might be required of them as the condition progresses.

Logsdon suggests that friends and family members look at this as a gradual process. “A child can say, ‘You know, Mom, I think there’s something going on with Dad and we should get him to the doctor,’” she said. “Be supportive of just first gathering all the information.” Logsdon pointed out that “it’s very hard for people if you hit them with the worst case scenario,” and it is instead more appropriate to act as a sounding board for the family caregiver as things change. “Listening, helping to do problem solving, thinking through alternatives, but not getting frustrated and upset with the caregiver if they can’t follow through on those things right away,” she said. “The most important thing I think is to keep a good relationship with the person that you’re trying to help.”

________________________________________________

What to Do:

• Be present and willing to listen

• Ask, “How can I help? What can I do?”

• Ask the care partner how they’re doing

• Ask what you can do to support the care partner’s wellbeing

• Educate yourself about dementia

• Offer to research support groups or day activity centers

• Be a sounding board for decision-making

• Engage the person with dementia in activities

• Provide the caregiver with respite when possible

• Bring food, do laundry or perform other small tasks

________________________________________________

Heuer, meanwhile, suggests asking the spouse what would be most useful — questions such as, “How can I help you through this? How can I support you through this process? What can I do?” Beyond that, emotional support is an immense assistance. “They just need someone to sit with them, not tell them how to make it better,” Heuer said. “Because [family] caregivers often do feel alone.”

Sometimes, asking questions can also help to elicit understanding of new and unusual behaviors for spousal care partners. Vincent Antenucci, research and training manager at the Ohio-based Center for Applied Research in Dementia, said that the environment of the person with dementia can trigger what he called “responsive behaviors” — excessive eating, wandering away, paranoid accusations or other challenging actions.

Sunlight on the walls or bedspread can look like spiders to those with dementia

By asking questions about potential triggers, such as the time of day that a new behavior occurs, Antenucci has found that spouses or other caregivers can gain understanding and adapt. Often, a person will act out because they’re understimulated, he said. In one instance, a woman with dementia, who had begun to see spiders, was actually responding to the pattern of the sunlight on a lacy bedcover at a particular time of day. Still, Antenucci warned that it’s important to ask questions rather than make assertions as spousal care partners are often overwhelmed and emotionally drained.

Experts agree that it’s best to avoid advice or opinions. Common unsolicited advice can include ideas about diet and nutritional supplements or even pointing out something obvious, such as the fact that the spouse with dementia can’t control their behavior. “Your telling them how to handle the disease from the comfort of your own home, when you don’t have to deal with it, is not really helpful,” said Dasha Kiper, the consulting clinical supervisor of support groups for CaringKind in New York. “It really undermines the emotional reality.” Kiper advised against acting overly optimistic or saying things like “Don’t worry, it will get better” — which simply isn’t true. That’s something people do to alleviate “their own discomfort, because they feel so uncomfortable hearing somebody’s bleak reality they try to put a positive spin on things,” she said.

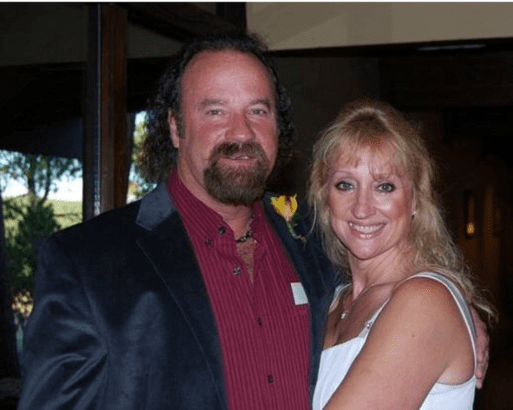

Spousal care partners can feel family, friends or even strangers are judging them for their approach. Jameson — who began dating, with the blessing of his wife’s two children, once she no longer recognized him — found that many people couldn’t accept his choice, despite the fact that he considered it beneficial for everyone involved. Tami Reeves faced similar circumstances when she dated a man named Eric, whom she met on Match.com and whose wife, Gaye, suffered from dementia. Despite the fact that Reeves became an active participant in Gaye’s care, boosted Eric’s wellbeing and confidence, was welcomed by his children and eventually married him, she often felt judged by the care home staff. “I know what they were thinking about me,” Reeves said. “This little hussy, with this man while he’s still married.” As a sensitive person, Reeves found it hard to take, and later wrote a book about her experience to counter such attitudes: “Bleeding Hearts: A True Story of Alzheimer’s.”

Tami Reeves with Eric on their wedding day

Relatively distant family members will often judge the spousal care partner for their choices, Heuer said. “I call those people quarterback caregivers because they like to say after the fact how they should have handled things, but they weren’t there in the first place,” she said. Instead, Heuer advocates offering reassurance to family caregivers, who typically judge themselves much more harshly than anyone else. “I try to provide the caregiver with a lot of reassurance: that you’re doing the absolute best you can with a very complicated disease,” she said.

Parker said it’s important to understand that a spouse may not be prepared to take on a full-time caregiving role — and that’s okay. “Spouses who’ve now got the responsibility of caring for all of the activities of daily living — bathing, toileting, feeding, meal preparation, laundry — that can become a very overwhelming task,” she said. The spouse should not feel guilty about hiring someone to perform some of these duties, Parker said. “Sometimes there are other people better suited to do that task so the spouse can continue to love their care recipient, and enjoy their spouse the way they want to,” she said.

Taking Action to Support a Friend Whose Spouse has Dementia

Once a diagnosis has been established, experts advocate encouraging the caregiver to receive training about the condition — and educating oneself as well. Heuer said that books such as “The Mindful Caregiver” by Nancy Kriseman or “The 36-Hour Day” by Nancy Mace and Peter Rabins are illuminating and can soothe spousal care partners while deepening their comprehension. “Some knowledge and understanding can help with interaction — even with the person that is the caregiver,” she said. “One of the biggest things is not to take things personally from the caregiver, because they’re going through a lot.”

Amy Torres, director of training at CaringKind

Credit: CaringKind

The Alzheimer’s Association offers free online trainings for family caregivers and others, while local chapters around the country provide training, education, support groups and other resources. Amy Torres, the director of training at CaringKind, which was formerly the New York chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association, said that in addition to training professionals, the center provides a 10-hour family caregiver workshop facilitated once a week over a month’s time. “Our goal is to ensure that the participants are able to better communicate with the people that they’re providing care and support to,” said Torres, who encourages family care providers to seek out training early on rather than waiting until they’ve reached a threshold. The course focuses on the clinical progression, common symptoms and expected behaviors, and introduces additional forms of support. “We want to ensure people are accessing social work services, people are maybe availing themselves of a support group. If they’re not ready now, they should be aware that it exists for the future,” said Torres, adding that ongoing seminars also cover topics such as understanding dementia, legal and financial planning, nursing home placement and Medicaid home care.

Stefanie Bonigut at the Grand Canyon in a “Walk to End Alzheimer’s” T-shirt

Stefanie Bonigut, the family services manager at the Alzheimer’s Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada, provides local follow-up for the national helpline, which offers confidential support and information to people living with dementia, their caregivers and others. She also leads workshops and facilitates support groups that can provide a nonjudgmental space for spousal care partners to vent their true feelings and be understood. “Even though every single one of them will be in a different situation, they just feel like everybody in the group gets it,” Bonigut said. “Unless you’re living with it, you don’t fully understand.”

Kiper, who leads small support groups for spousal caregivers and others, said participants feel able to share thoughts such as “I want to divorce my husband,” or “I wish my wife was dead,” that are rarely, if ever, voiced outside the group. Even so, she said, family members and friends can offer up space for spousal care partners to express the depth of their struggles. “Any friend who wants to be there — or child, really — it’s an invitation to talk about those things,” she said. “Or sometimes, just to chit-chat and have a good time, depending on what the spouse needs.” Kiper advocates calling family care partners up and offering assistance. “The answer is likely to be ‘no’ because caregivers have a very hard time giving up control,” Kiper said. “But everybody likes to be asked.”

Bonigut said that sometimes family caregivers aren’t sure what they need. She encourages them to make a list of what they require or would appreciate and post it on their fridge so that when someone asks, they’ll know what to say. “I always tell caregivers that they should ask for and accept any offer of help,” Bonigut said. Family and friends who know the caregiver well can offer to bring food or come over and start cleaning or doing yard work, she said.

People can often see what someone needs and step in to provide that assistance, Parker said. “We’re always asking for permission to do something,” she said. “Just do it.” Sometimes the person with dementia is the one who always did the driving, so you can offer to drive that spouse to the doctor’s office or the grocery store. Meanwhile, adult children who live far away can send funds to hire additional support, she said.

Kathy Stewart suggests being a sounding board

Credit: Aegis Living

One thing people can provide for a friend whose spouse has dementia is a sounding board for decision-making. Individuals will not only be faced with tough choices about their partner’s care, but they’re also losing the very person they once turned to for guidance in financial, personal and other matters. “Offer to help the caregiver plan ahead and prepare,” Stewart advised. “Help them organize their finances, find important documentation, or seek professional help from a financial advisor.” Stewart warned that it’s important to keep an eye out for fraud, as while the person with dementia is clearly more vulnerable, an overburdened care partner could become susceptible as well.

Supporting the Family Caregiver’s Health & Wellbeing

The challenges faced by spousal care partners place great strain on their mental, emotional and physical wellbeing. An estimated 40% to 70% of family caregivers experience significant symptoms of depression, with both men and women reporting that caring for a spouse or child is more stressful than caring for an aging parent. Meanwhile, a 2007 meta-analysis of 176 studies published in The Journals of Gerontology found that informal caregivers exhibit worse physical health than non-caregivers, with 18% to 35% perceiving their health as fair or poor.

Bonigut says that she often presents caregivers with the airline safety analogy — the fact that you can’t help anyone else until you’ve donned your own oxygen mask. “It’s not selfish to take that self-care time,” she said. Caregivers have difficulty scheduling respite — time to exercise, go for a walk, see a movie, or simply run errands. During the pandemic, some have gotten creative: One woman had a home care person come in so that she could hide out in her bedroom alone, Bonigut said. Another had a care provider read to the person with dementia over Zoom for an hour. A major supportive action that people can provide – yet rarely think to offer — is simply to sit with the person with dementia and make such time available, Bonigut said.

Another option is to take the person with dementia out or hire a care companion to take them out. In Parker’s experience, male dementia patients in particular appreciate the opportunity to engage with other men — golfing, visiting the barber or attending a baseball game. Parker recalled one 95-year-old patient whose daughter asked people to celebrate her mother’s birthday by donating their time in lieu of gifts and set up a calendar with options to sign up for a couple of hours. Still, Parker encourages anyone involved in caregiving to obtain some training, so that they know what to expect — that the person could just get up and wander away, for example.

Taking the person who has dementia or the caregiving spouse out for a walk provides respite.

Logsdon suggests a friend or family member set up specific days to spend with the person with dementia to go for a walk, get an ice cream, or engage in some other activity they enjoy. By building the relationship over time, the family caregiver can also feel comfortable that the person knows how to interact with the care recipient. “Caregivers are often reluctant to leave their loved one with someone who they think really doesn’t understand what to do,” Logsdon said. When interacting with people with dementia, she said, it’s important to avoid quizzing them, or correcting what they say — no matter how bizarre. Instead, she suggests redirecting the conversation and chatting about things in the distant past.

Vincent Antenucci recommends actively engaging the person with dementia.

When engaging the person with dementia in meaningful activities, such as fixing things or putting in a garden, Antenucci advocates involving them as much as possible. “Treat them the same way as you always did, and don’t assume that they’re going to have responsive behaviors,” he said. Antenucci stressed that it’s important not to ignore, sidestep, or simply take over from the person with dementia, citing an instance in which a father with dementia became furious when his adult children decided to surprise him by painting his house. “They didn’t consult with him, they didn’t ask him, they didn’t ask for his help,” Antenucci said. “It would have been a great opportunity to spend meaningful time with him doing something constructive.”

It can also be a good idea to invite the caregiving spouse out — for coffee, or a walk, or some other activity. “As a friend, I think it’s your job to very, very gently ask them how you can help them take care of themselves,” Kiper said. Even if they’re not ready, “they feel that actually they’re needed by the outside world and missed.” Kiper added that getting the care provider out of the house has the added benefit of putting some light pressure on to find additional help.

Spousal care partners are often reluctant to seek assistance, no matter how much it’s needed. Bonigut said that day centers offering arts and crafts, games, music, movement and other activities provide one way for care partners to ease into gaining some support. “They’re so good for the person with dementia,” Bonigut said. “And then it gives the caregiver time off.” Such programs can also reduce the dementia patient’s dependency on the well spouse, whom they often begin to view as a “security blanket” and shadow constantly — even to the bathroom, Bonigut said. Still, many spouses struggle with the fees, which can be $100 a day, while in-home care is around $35 an hour with four-hour minimums. “People are petrified about how they’re going to pay for care,” Bonigut said. “Which is why caregivers tend to do it themselves.”

Logsdon said that day activity centers are one way to ease a family caregiver into giving up control, as are housekeeping and home healthcare services that gradually increase their hours over time. As the condition progresses, a friend or family member can also assist a care partner to visit long-term care facilities and explore available options, Logsdon said. “Looking at what the resources are, how can we pay for them, how do you feel about this kind of place,” she said.

________________________________________________

What Not to Do:

• Offer advice or opinions

• Say that you understand what they’re going through

• Judge, criticize, or make demands of the care partner

• Ignore, quiz or talk down to the person with dementia

• Show up and make changes to the environment

________________________________________________

Sometimes a spousal care partner in a challenging situation may become avoidant or withdrawn. In such circumstances, Stewart suggests bringing over a meal and getting in the door to see what’s going on. “That could be the first way to speak about the truth,” she said. From there, she said, you can suggest additional help — such as bringing in home care or alternating family members to provide meals. At Aegis, she said, family caregivers can arrange a temporary stay of a week or a month for the person with dementia so that they can recover and consider what to do next. “When you’re in it so deep, you can’t even process or think or plan,” said Stewart, who’s written a book about caring for dementia patients called “Mom’s Losing Her Memory, I’m Losing My Mind!”

While there is a host of services available and numerous ways to offer support, experts say that a friend or family member’s simple intention to help is what a spousal care partner will value most. Jameson, who spent a good deal of time traveling with his wife to countries including China, India and Egypt following her diagnosis, said he was touched by the way strangers often stepped in to assist them. “It was a wonderful, beautiful experience,” he said. With dementia, “life is not over, and joy and humor and all the range of emotions, both positive and negative, are still viable,” he said.

Ginny with their cat, Rudy

Often, it was the people closest to Ginny who couldn’t handle her condition. When she was dying in hospice, there were several people who’d loved her throughout her life but felt they couldn’t come to see her. “That was hard,” said Jameson, who nevertheless understood. When he explained to Ginny that they were moving her into full-time hospice, a tear came to her eye — an indication, he believed, that she knew the end was near. “At a subconscious and even conscious level, even somebody with dementia understands their environment,” he said. “If you’re trying to support somebody, the idea isn’t to dismiss it or walk away. If you can deal with it, stick around and be a sounding board or a shoulder to lean on.”

What to Say to a Friend Whose Spouse Has Dementia

What to Say to a Friend Whose Spouse Has Dementia

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!