A mural on Venice Beach by Pony Wave.

Credit: Pony Wave (@ponywave)

Since the coronavirus outbreak, we live in altered landscapes. Skies have cleared; highways are quiet. Stages and stadiums lie eerily vacant, and on a walk through your local downtown, you’re likely to be faced with dark windows and empty streets. And you might be faced with something else: a new world of street art.

In a time of social distancing and isolation, public art — sanctioned or otherwise — has emerged as a means of sharing communion, solidarity, and appreciation for those on the front lines.

“Super Nurse” by FAKE.

Credit: FAKE (@iamfake)

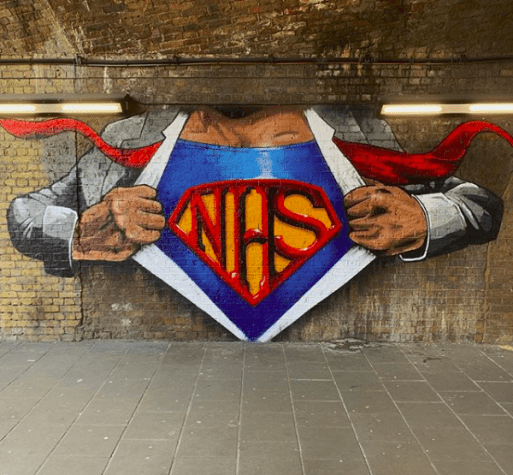

A mural by Lionel Stanhope honoring the UK’s National Health Service.

Credit: Lionel Stanhope (@lionel_stanhope)

“Public art” can have two very different meanings, depending on whom you talk to. In the more traditional sense, public art is something made by established artists and commissioned by professional curators. But it can also refer to unauthorized graffiti, “tagging,” and temporary installations.

There’s been an undeniable surge in both types of public art during the COVID-19 pandemic. In lieu of gallery shows and museum exhibits, many arts institutions are inviting artists to work in public spaces. On the other end of the spectrum, graffiti artists are making their own mark on unsupervised streets with creative visuals and social commentary.

Beautify, an urban renewal nonprofit based in Santa Monica, falls somewhere in the middle. The organization has worked with local artists and business owners to place “COVID-19 response murals” on public buildings throughout the country. Evan Meyer, Beautify’s CEO, told the New York Times, “This is an opportunity to keep the streets alive and reduce recovery time.”

A mural by Beautify artist Ruben Rojas.

Credit: Ruben Rojas (@rubenrojas)

While Beautify got its start by using vacant or abandoned buildings as its canvasses, “vacant” has taken on a new meaning in the era of COVID-19. Many restaurants, retail stores, and other businesses under lockdown have utilized their own dormant spaces, from homemade signs to elaborate commissioned works.

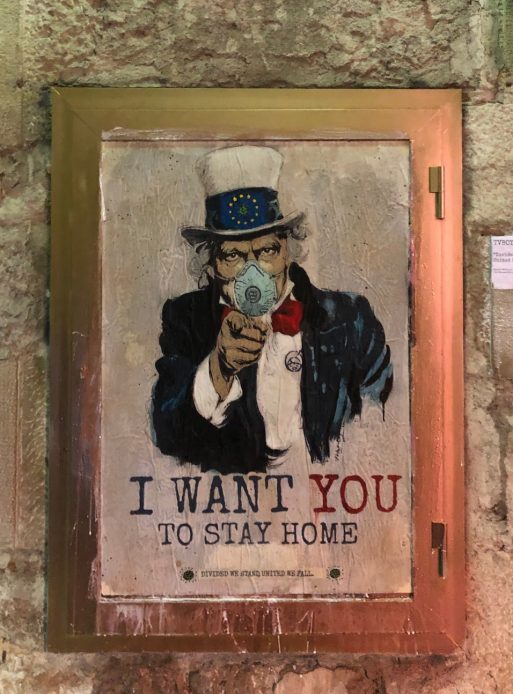

Dr. Heather Shirey of the University of St. Thomas has begun cataloguing coronavirus-themed street art in a crowd-sourced online database called Urban Art Mapping: COVID-19 Street Art. Shirey notes some consistent themes in the art that’s emerged around the pandemic, such as the “public service messages” that urge onlookers to wash their hands or stay home.

“Divided We Stand, United We Fall” by TVBOY.

Credit: TVBOY (@tvboy)

Many works serve as homages to essential workers, depicting nurses and teachers as angels and superheroes. Shirey also points to the “generalized messages of hope, love, and unity can be found in art around the world.”

“Love in the Time of COVID” by TVBOY.

Credit: TVBOY (@tvboy)

“I am seeing some artists using their work as a platform to reveal the social, economic, and racial inequities that are made even more apparent by this crisis,” Shirey said. As she observes the patterns emerging in the present, she wonders about the future: “I anticipate that we will see more street art that reveals our collective sense of loss and trauma, as well as other responses that will likely emerge over time: loss, sorrow, and grief, for example.”

The future is always uncertain, and perhaps never more so than now. But we know that art, as it always has, will be a vital element in seeing us through whatever that future may hold.

A New World of Street Art Has Emerged Under Lockdown

A New World of Street Art Has Emerged Under Lockdown

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls

“Summons” by Aurora Levins Morales

“Summons” by Aurora Levins Morales