Credit: seattle.winstonwachter.com

You’re more likely to see still life vanitas hanging on the walls of historic art museums than in modern art galleries. This distinctive style of Dutch art, which reached peak popularity in the 16th and 17th Century, isn’t nearly as popular among modern painters and sculptors as it once was. But artist Dirk Staschke has decided to revisit this classic style of art in his latest collection, “Perfection of Happenstance,” currently showing at Winston Wachter gallery in Seattle.

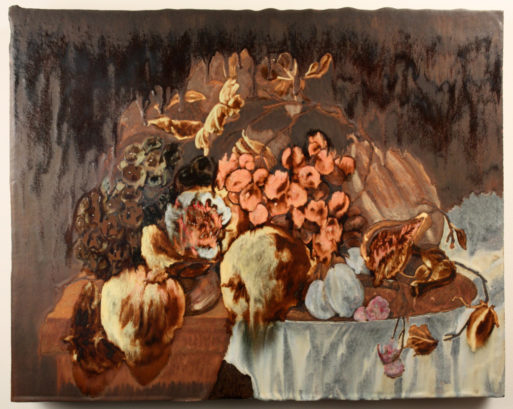

You won’t see bold swaths of color or sharp patterns in Staschke’s work. Like the classic still life vanitas of the 17th Century, his work is both hyper realistic and surreal all at once. The dulled-down tones of brown and tan make every painting look as though it’s bathed in soft candlelight; it harkens back to a time before electricity existed in every home, and rooms were filled with stark natural light. Yet this extreme realism is balanced out by the unnatural placement of the objects in the frame. Like all still life paintings, Staschke carefully selects each object to represent larger symbolism.

Credit: seattle.winstonwachter.com

This is a crucial element of still life vanitas. The paintings most often feature a variety of objects sitting on a table. Fresh flowers, ripe fruit and glimmering jewelry rests on the table next to a human skull, or other objects strongly associated with death. The strange placement of these objects together on a single table gives the art an unnerving feel. It reminds us that even as we gaze at things of beauty that are full of life (such as a plump orange, or a delicate orchid), death still sits close by. It’s ever-present in the frame.

Dirk Staschke takes a literal approach to some of his still life vanitas. In his piece “Flux 9,” he paints a stunning scene of a rotting flower bouquet, with each petal slowly turning the same shade of muddy brown or mauve. The flowers look almost as if they’re melting down to the base of the frame. This is a nod to 17th Century still life vanitas symbolism; the flowers represent life, whereas their slow, melting decay represents death.

But Staschke goes beyond some of this more obvious symbolism with his other pieces in the collection. Rather than sticking with paint as a medium, he carves out intricately-adorned frames that are absolutely dripping in regal beauty. And, in classic vanitas fashion, he turns this beauty on its head with the stark scenes inside of the frame. In some of his pieces, you can literally reach in and touch the objects inside of the frames if you wanted to. It takes the realism of vanitas and amps it up significantly, making the symbolism even more difficult to ignore. It’s like vanitas that have come to life before our eyes.

Credit: seattle.winstonwachter.com

He also applies this technique to his delicate ceramic pieces, once again using a painting technique that makes the scenes look as though they’re melting. In these works, it’s difficult to even see what some of the objects are, especially up close. On the micro level, they look like beautiful watercolor patterns, with a bit of a floral bent. But when you back up and view the ceramic pot from a distance, you can see the clear shape of an abstract skull in the scene.

In this sense, Staschke takes the concept of vanitas to the next level. He forgoes some of the style’s classic realism in favor of something that looks a little more dreamlike, but that nonetheless reminds us of the fragility of life. He offers us a new perspective on an old art style, proving that this symbolism will forever hold a place in our minds. Whether it’s 1617 or 2017, we can appreciate vanitas as a constant reminder that life and death are locked in an intricate dance, from now until the end of time.

Bringing 17th Century Still Life Vanitas Into the Modern World

Bringing 17th Century Still Life Vanitas Into the Modern World

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?