Death masks have a long history, dating back thousands of years. In the absence of photography, they were an excellent way for the still-living to remember and commemorate their loved ones who had died.

And now, Neri Oxman and her team at MIT’s Mediated Matter Group have revealed the final addition to a new-age death-mask series meant to represent the journey between life and death.

The series, called Vespers, is a trilogy of death masks representing the past, present and future. The three sub-series are comprised of five masks. Each mask belongs to a fictional martyr, and the masks “evolve” from the first series to the next, so every martyr has three masks that correlate directly with each other. (Five martyrs, three masks each, one from each series.) The masks were constructed using a Stratasys 3D printer, which deposits polymer droplets in multiple layers.

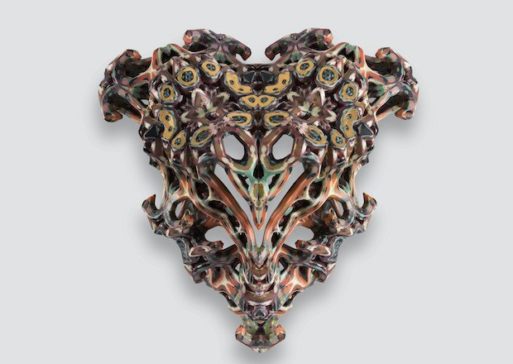

The masks themselves are wildly different shapes, sometimes appearing not altogether of this world. Some masks look like large, glass seashells with dashes of vibrant color strewn throughout. Some almost resemble a giant, colorful nautilus, with others appearing gem- and ice-like. They were created using algorithms based on biology and different natural orders of life, emulating cellular division.

Series I (Past, The Natural World)

One of the death masks from Vespers: Series I. Credit: tctmagazine.com

The first series pays homage to the death masks of bygone eras, and the designers drew inspiration from ancient cultures. The five color combinations utilized in this series were derived from different religious practices traversing both regions and eras. The masks are also embedded with natural minerals like bismuth, silver and gold.

The technology used to create the masks in the first series was vital to their construction. According to the Mediated Matter website, “The implementation of the Stratasys full color multi-material 3D printing technology enables the creation of objects — for the first time in the history of additive manufacturing — that match the variety and nuance of ancient crafts.”

Three-dimensional printing enabled the team to emulate styles from bygone eras, simultaneously rejuvenating the ancient art of death masks.

Series II (Present, The Digital World)

Part two represents the metamorphosis between parts one and three. The colors and shapes of the first series influenced the death masks in part two, owing to the intended evolution of the masks from series to series.

All five masks from Vespers: Series II. Credit: dezeen.com

“Present, The Digital World” also bridges the gap between parts one and three because it represents the advancement of the death mask from ancient relic to what the designers call a “functional biological interface,” which is represented by the masks in part three.

They mention on their website the idea of “the soul’s journey,” and they represent this by having both interior and exterior portions of the masks.

“The inner structures are entirely data driven,” write the designers, “and are designed to match the resolution of structures found in nature. Expressed through changes in formal and material heterogeneity — from discontinuous to smooth, from surface to volume, from discrete to continuous — this series conveys the notion of metamorphosis.”

The jargon used to describe the processes/algorithms that created these masks is pretty technical. Inside the masks are pathways of sorts, internal structures that help to create the designs we see. Light moving through the masks reveals these structures. The masks in series two resemble something that might come from the “Alien” vs. “Predator” movie franchise. Nevertheless, they are all beautifully colored and seem as if they’re made of glass clouds.

Series III: Vessels For New Life

Technology and nature don’t always seem to be forces that could work successfully in tandem. After all, people today head for natural areas to escape technology. However, in the final part of the Vespers series (“Future, The Biological World”), Oxman and her colleagues were able to meld biology and technology and manufacture what are essentially habitats for microorganisms.

One of the “biological” death masks from Vespers: Series III. Credit: dezeen.com

These death masks start off relatively colorless, but via internal structures similar to those employed in the second series, microorganisms and their byproducts reinterpret colors from the first series. This serves to “biologically recreate” the cultural death mask which was its precursor in the first series.

“The living masks in the final series,” the designers write, “embody habitats that guide, inform and ‘template’ gene expression of living microorganisms. Such microorganisms have been synthetically engineered to produce pigments and/or otherwise useful chemical substances for human augmentation such as vitamins, antibodies or antimicrobial drugs.”

The designers claim that they could use this technology to create beneficial microbes for use in everyday applications. They list antibiotic and cosmetic production, “environmentally responsive architectural skins” and smart packaging that could detect contamination as some possibilities.

“Vespers” is a very interesting series. It’s hard to grasp the technology behind the creation of the masks, but the final products are very intricate and exquisite.

The series transitions from paying homage to the ancient practice of making death masks, to metamorphosing into vessels intended for the creation of new biological life. It’s an interesting and certainly original way of imagining the transitions from life to death and back to life.

Death Masks Created by 3D Printer Symbolize Journey From Life to Death

Death Masks Created by 3D Printer Symbolize Journey From Life to Death

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull