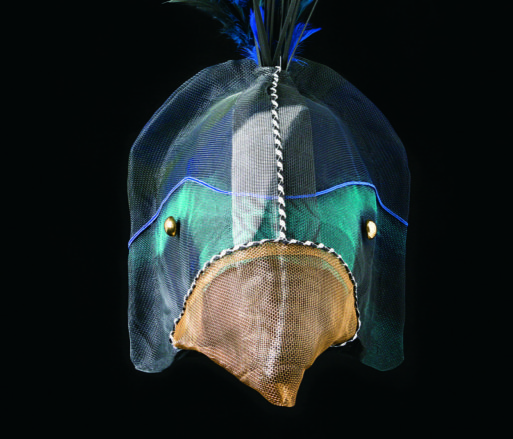

Avian Warrior II by Joan Konkel

Credit: Ulf Wallin Photography via artsy.net

For the uninitiated, the very idea of radiation therapy is frightening enough. The implications of the treatment for the human body are obvious. Radiation powers nuclear weapons — it’s counterintuitive to think it could possibly be good for you.

But when you have cancer, you do a lot of things that your logical brain says you should never do. You submit to disfiguring surgeries, toxic chemotherapy, and — yes — you lie down on a table and allow your body to be bombarded with a proton beam.

For people with head and neck cancers, the latter indignity is heightened by the use of a specialized device that keeps the head completely immobile, an important precaution that keeps the tissues surrounding the radiation field relatively safe. It looks like a Medieval torture device, but in common parlance, it’s known as a radiation mask.

Made of plastic mesh and fitted with snaps that hold it fast to the table, radiation masks are customized for each patient. The plastic is heated slightly so it can be easily manipulated and then applied to the person’s face. It must sit there until it hardens, molding itself to the person’s facial contours like a well-fitted glove. Doctors tell us the process is not uncomfortable and it’s easy to breathe while the mask is on. People who have had to wear them provide differing accounts.

An unadorned radiation mask worn by a patient with head and neck cancer

Credit: Ryan Leahey via artsy.net

For many people who have journeyed through treatment for head and neck cancer, these masks become a symbol of what they have endured — a tangible reminder of struggle and survival. For some of them, that symbolism is so powerful that they have turned their radiation masks into art.

Carol Kanga is one of those people. An artist and a survivor of head and neck cancer, she wanted to celebrate her life and honor the safety and solidarity the mask represented for her. “It meant precise treatment, the best available,” she told Artsy. “When I walked into the radiation room and looked up at the shelves, scores of masks looked back at me. They signaled that I was not alone, that hundreds of people get through this, that each of us is a distinct individual receiving excellent treatment tailored exactly to each contour of our bodies,” she said.

Kanga connected with fellow cancer survivors through Courage Unmasked, a group founded by Cookie Kerxtson in 2009. Inspired by her own recovery from head and neck cancer, Kerxton wanted to help other patients who were struggling with the physical, psychological and financial after-effects of therapy, most of which she had been fortunate enough to avoid. So she asked a local treatment center if she could take home radiation masks that patients had left behind. She then asked her artist friends to decorate the masks, turning them into saleable works of art.

Athena’s Owl by Barbara Kearne was inspired by the Greek goddess of arts and crafts, who often took on the shape of an owl

Credit: Ulf Wallin Photography via artsy.net

Courage Unmasked held its first auction at American University’s Katzen Arts Center in Washington, D.C. On display were 108 masks created by over 100 artists, some cancer survivors, some not. The proceeds from the auction were distributed through Kerxton’s Maryland-based nonprofit 9114HNC (Help for Head and Neck Cancer) to head and neck cancer patient’s in need.

Since then, other groups have taken up the challenge of turning radiation masks into art. Meanwhile, Courage Unmasked has continued to sponsor auctions and raise money through the sale of posters, catalogs, and other events. The group is also committed to raising public awareness of head and neck cancers, many of which are now preventable with a vaccine.

Decorated Radiation Masks Turn Suffering into Art

Decorated Radiation Masks Turn Suffering into Art

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”