A post-mortem exhibit of Kevorkian’s oil paintings at the Armenian Library and Museum of America in Watertown, MA. Kevorkian was the son of immigrant Armenian parents.

(Credit: caveviews.blogs.com)

Jacob “Jack” Kevorkian (May 26, 1928 – June 3, 2011) was known widely as “Dr. Death” for his highly politicized pioneering efforts to legalize assisted dying in the United States. In 1991, a judge dismissed a murder charge against Kevorkian, describing his work as “a big service” to the public by bringing the issue of assisted dying to mainstream attention. However, Kevorkian was ultimately sentenced to a prison term of 10-25 years in 1999. After serving eight years, he was released on parole at the age of 79 and never again offered suicide counsel. His paintings reflect the anguish that he witnessed in his patients, and which he himself experienced as a helper with limited means to do the work he and so many others deeply valued.

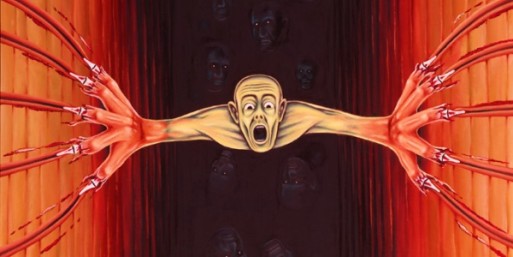

“Nearer My God to Thee”

(Credit: wnd.com)

“Nearer My God to Thee” is one such piece that illustrates this anguish and points to its source. The title of the painting is a reference to a popular Christian hymn which declares that life’s trials and joys are but stairways to heaven — all earthly experiences are vectors by which one can come ever closer to God. Kevorkian’s take on this perspective is filled with doubt and fear — perhaps his patients’ as well as his own. In this painting, we see the reverse imagery of the hymn — instead of stepping buoyantly to heaven, the central figure seems to be slipping into hell, with a painful effort to resist the descent. Perhaps Kevorkian means to describe the personal hell created by resisting the inevitable (in this case, death itself?), as well as the existential deathbed crisis that many superficially or culturally religious people face during their dying time. (Other paintings that illustrate this widespread spiritual crisis in America include “For He Is Raised” and “Fa La La La La, – La La, – La, – LA!“) This crisis summons questions like, “What happens to me after I die?” and “Was I a good enough person to deserve heaven?” and “Does heaven exist? Does hell exist? Is there any continuance or comfort beyond my present hell-state of worldly suffering?”

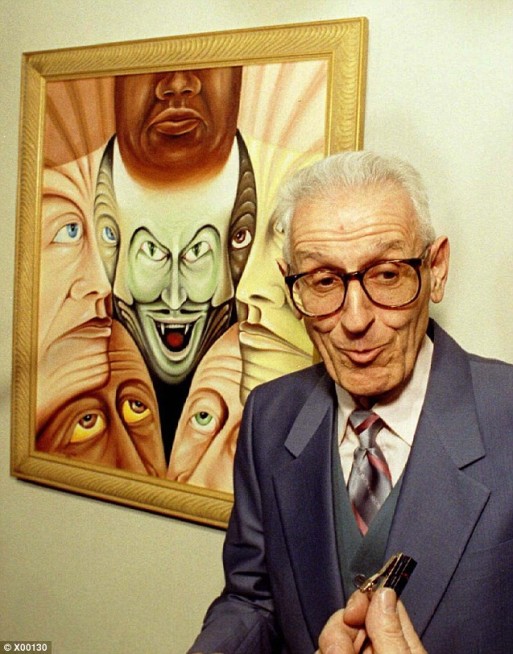

Dr. Kevorkian with his painting “Brotherhood”

(Credit: dailymail.co.uk)

In the culture of ancestral orphans that dominates North America, many individuals are left to ponder these questions without community support, or anyone to guide them through an understanding of their beliefs and values. In such a predicament, it is no wonder that an individual might feel alone and desperate. With nothing in their past (such as a rite of passage) to hold on to while being drawn inexorably toward the inevitable, they have no idea how to navigate the experience of dying or what to expect. As shown in Kevorkian’s paintings “Brotherhood” and “Paralysis,” this manifests in internalized conflict and fragmentation of identity.

Whereas spiritual traditions the world over place emphasis on unity and wholeness, it was the lack of authentic, supported engagement and understanding of these concepts that plagued Dr. Kevorkian’s life and work. They haunt his paintings and beg that we remember the man behind the controversy as a seeker of meaning and compassion.

Read more about Dr. Jack Kevorkian’s life and work on SevenPonds here and here.

Estate of Dr. Death Includes Original Oil Paintings

Estate of Dr. Death Includes Original Oil Paintings

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One